When Japan Made Volleyball Magic

A fascinating new film documents the dedication and prowess of the Japanese volleyball team, whose 1964 Olympic Gold changed the perception of women’s sport forever

By Emily Gosling

Unsurprisingly, the “Witches of the Orient” were initially unimpressed when they discovered the nickname they’d been given. As the best women volleyball players in the world, there were innumerable more flattering things they could have been called. But, as they discovered while touring Europe, “witches” didn’t have to just mean haggard, cackling evil-doers. It started to make sense: their skill was almost supernaturally brilliant.

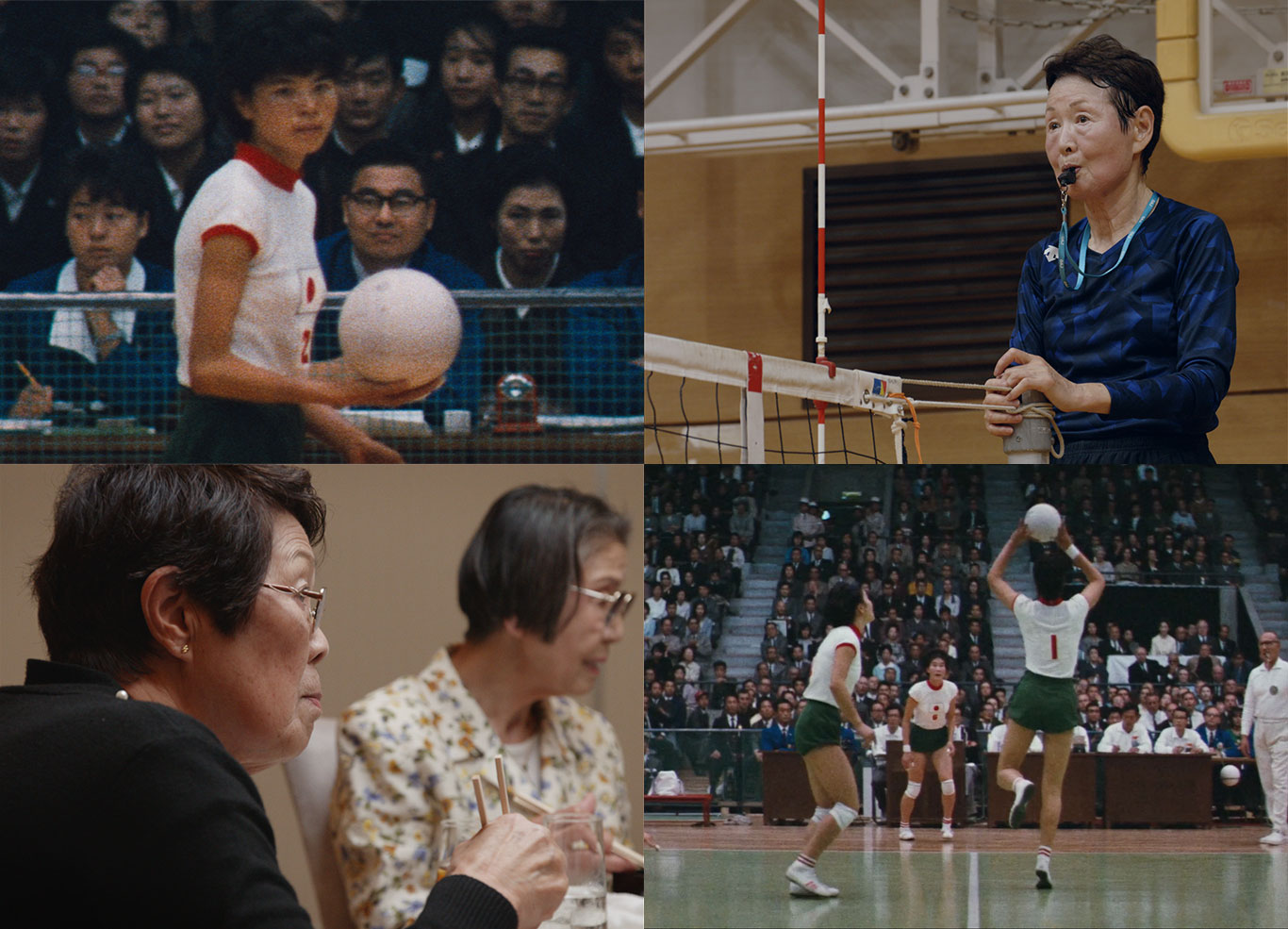

These “Witches”, as even they affectionately term themselves today, were the Nichibo Kaizuka team, who wowed fellow players and non-sportspeople alike when they won the Olympic title in Tokyo in 1964, at the sport’s first inclusion in the games. Their story is remarkable, as delineated in Julien Faraut’s new film, The Witches of the Orient.

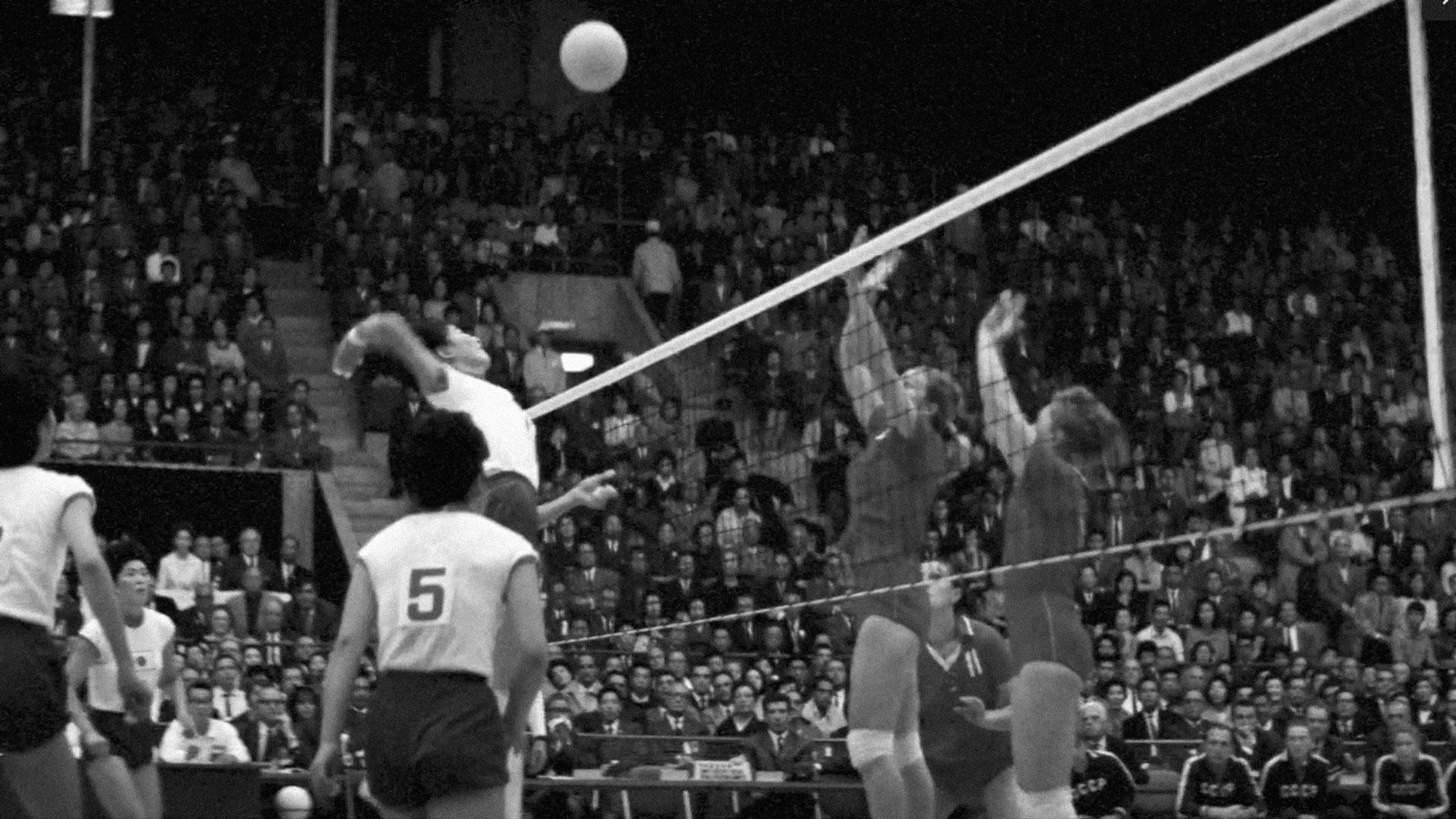

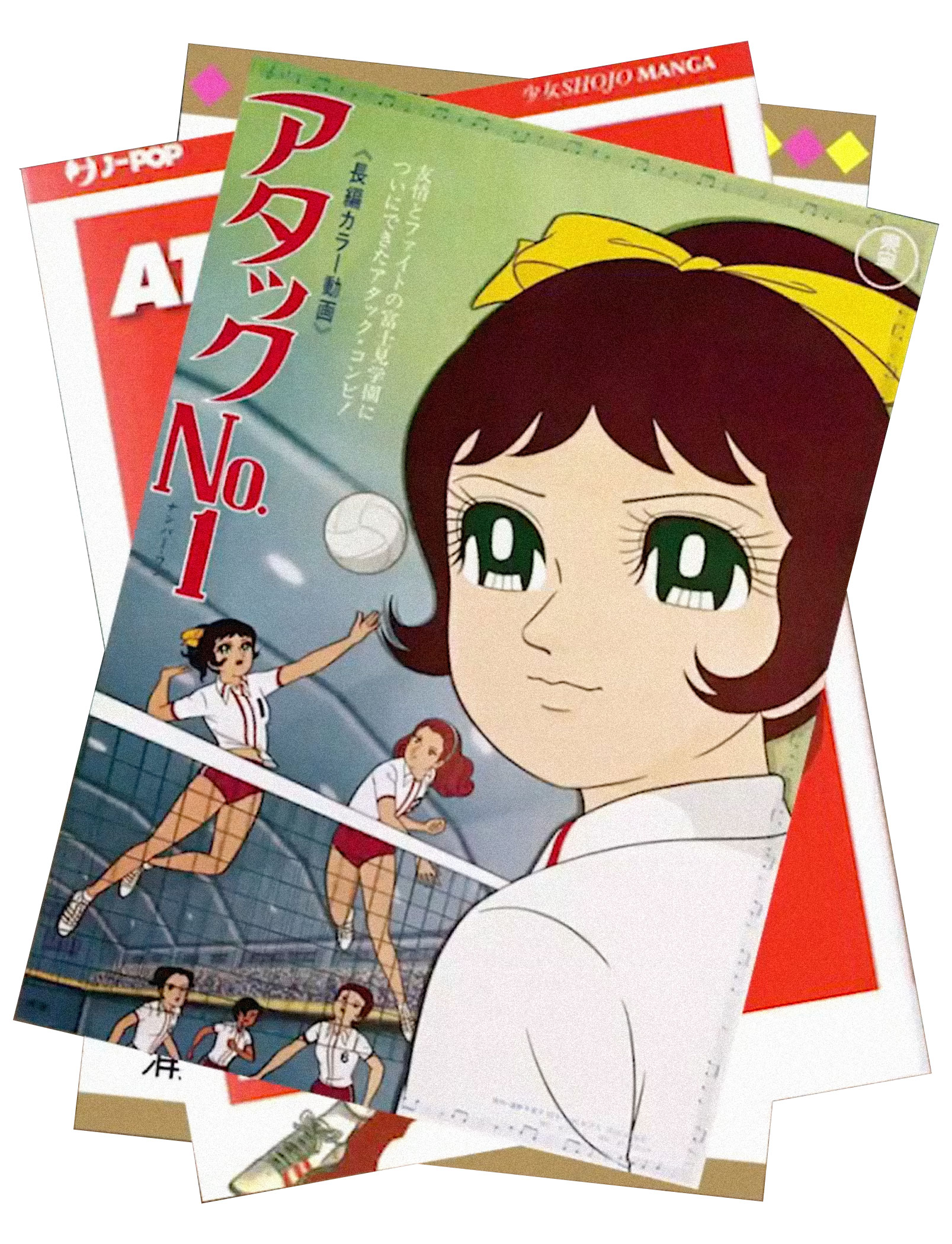

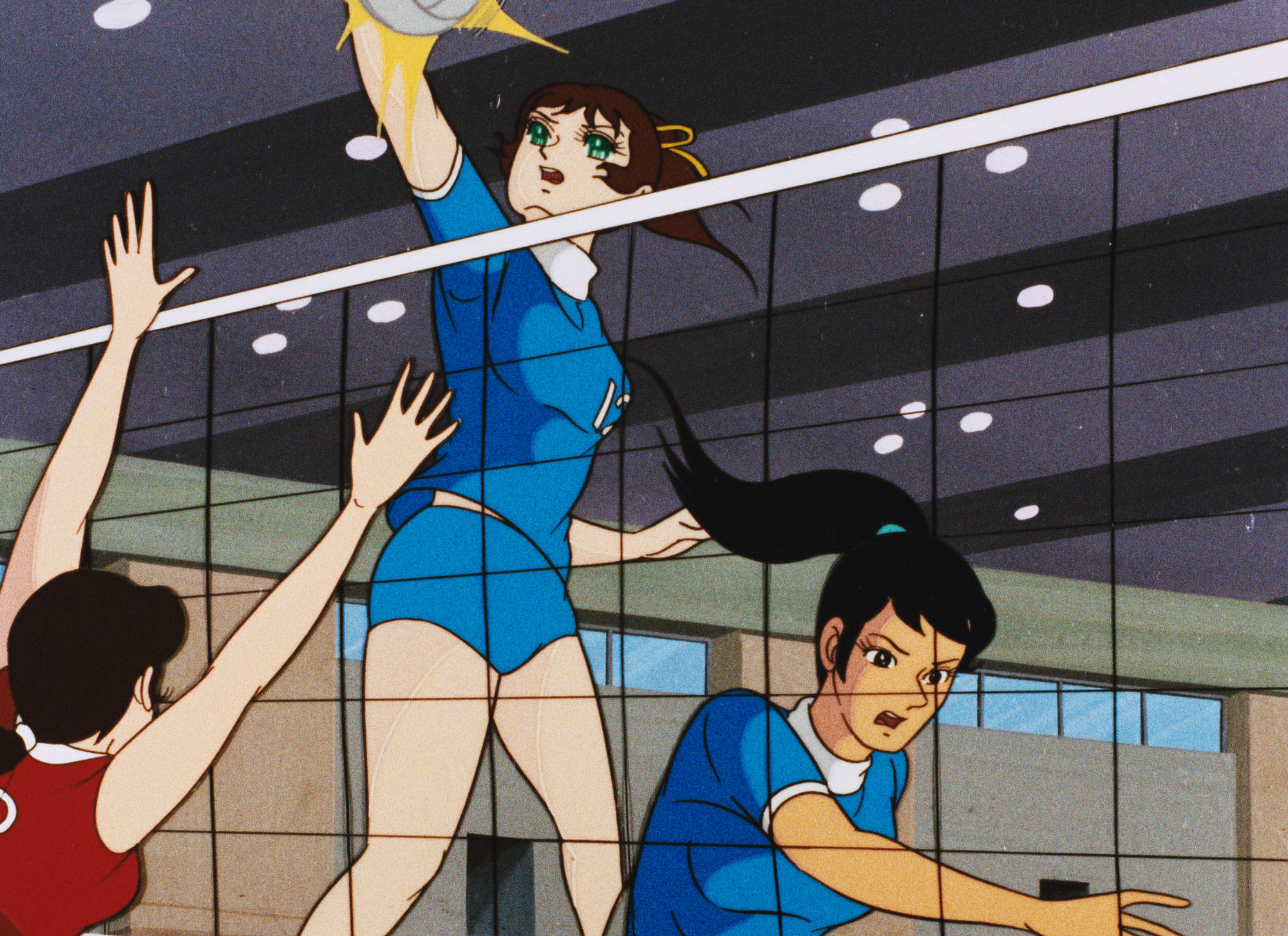

The film merges strikingly vivid, crisp archive footage (Faraut works at the Institut National du Sport, de l’Expertise et de la Performance in Paris, where he supervises a collection of 16mm films) with 2019 documentation of the director’s trip to Japan to meet the women, now in their seventies and eighties; as well as snippets of the many anime cartoons they inspired. “I really like to learn from the archives, rather than using footage to illustrate what I have in mind or already know,” says Faraut. “The intensity of their training was very unusual back in the ’60s in women’s sport.” He adds, “These are not ordinary women: they are superheroes.”

The movie’s dynamism often relies on its rhythmic, percussive approach to storytelling through the motoric beats of its soundtrack (largely music by Grandaddy’s Jason Lytle, K-Raw and, in a memorable stroke of genius, Portishead’s brutal Machine Gun). These reflect not only the team’s measured, relentless daily training regimen, but also the era itself. These are the sounds of post-war industrial revolution, of exactitude and precision, with the innovations unique to mid-century Japan underscored by the beguiling vacillations of vintage synthesisers. Faraut fell in love with the Witches’ story in part because it’s an archetypal, hard-to-resist tale of the triumphing of the underdog; and an equally seductive portrait of a group of people quite literally living, breathing and working (day jobs, as well as training) as a team.

Unlike in countries such as the US and the UK, where high-level sports are frequently backed by governments or universities, in Japan, they’re often organised and financed by large corporations – in this case, the Nichibo textiles company. Recreational sporting activities were offered to those living in factory residential compounds, in order to keep workers busy outside of work hours, maintain their physical health and encourage teamwork. Volleyball was the sport of choice for many textile factories, since it required minimal equipment and could be set up both indoors and outdoors.

Superheroes

As the popularity of volleyball rapidly grew in Japan in the ’50s, Nichibo soon realised the potential of the sport beyond recreation and employee health. In 1954, the company hired former player Hirofumi Daimatsu to build a competitive team formed of brilliant volleyball players who were employed in its factories around Japan. He chose to situate the team in Kaizuka, a small town just south of Osaka. “He created a great sense of partnership and team spirit: they were very close because they all lived together and worked together – they were a team all year long, not just for the national championships,” says Faraut.

The figure of Daimatsu feels ambiguous. On one hand, Faraut speaks of him with reverence (he’s not alone: according to the International Volleyball Hall of Fame, “many recognise him as the coach who revolutionised training for all women’s sports”). On the other, the film dramatises the gruelling training regimen that Daimatsu put the women through, earning him the reputation and nickname “The Demon Coach”. The team’s days were always the same: up at 6am, factory work until 12pm, lunch, gym, volleyball training until anywhere from midnight to 3am, depending on how the session was going.

dynamism

The ambiguity arises in how the women speak of such a regime: they emphasise that they made the decision to stay and train – captain Masae Kasai chose the team over the man she was engaged to. In a telling segment of the film, one of the players reveals that only two of the team members had both parents, and describes their view of Daimatsu as both father figure and the sort of man they wanted to marry.

The women often refer to their gratitude to Daimatsu, narrating his techniques as observers rather than critics. Faraut hints that the Witches’ methods likely felt uncomfortable to supposedly “progressive” Westerners, since it was likely the first time they’d been aware of female athletes training in such a way, “like men did,” he says. “It was interesting to discover that in Japan, which was a very misogynistic and patriarchal society, there was a man with a military background who just said, ‘Okay, I will train those women like men, because I know that women are capable.’”

Such cultural assumptions are perhaps another reason – aside from the obvious racist undertones – that they were dubbed “witches”, rather than a more celebratory nickname that underscored their prowess. In the historical contexts the film depicts, Daimatsu could be seen to be as much a product of his time as his team. He served in the Second World War under reportedly horrific conditions, leading a platoon of 40 men across treacherous, mountainous territory with no food and with many suffering fevers, malaria and/or amoebic dysentery. In short, he was tough. But his divisive methods worked: the team achieved 175 consecutive wins under Daimatsu’s training.

Faraut’s editing interweaves sports footage with documentation showing the post-WW2 devastation that blighted many Japanese cities, the terrifying billowing majesty of mushroom clouds, the surge towards an industrial future built around factory-floor precision after the war. “You can’t understand the story without knowing the context of Japan in post-war time,” says Faraut. “The Japanese made an amazing collective effort towards rebuilding, because the country was destroyed. The team was in the middle of something more expansive going on in society. They trained in an almost industrial way.” Key to the story of the Witches’ success is their dominance over the USSR, and the film seems to suggest volleyball as a political rivalry as much as a sporting one.

awe-inspiring

The team’s factory-based roots hint at the theme of class that gently bubbles beneath the prevailing narratives of awe-inspiring athletic and mental feats and female camaraderie. As Faraut was keen for the film to spell out, the women are not from wealthy backgrounds (they list their parents’ jobs as milk sellers, farm workers and labourers). Their hiring by Nichibo wasn’t just an opportunity sports-wise, it also offered a significant promotion from their former jobs for most of the women: rather than working the machines, they took on more supervisory, less manual roles. “Volleyball was valuable, it was the reason they were promoted,” says Faraut.

confidence

While the director goes on to say that these promotions made the women “very happy and proud”, he’s emphatic that this is their story to tell, not his. He shows the women enjoying lunch together, gently highlighting the intimacy, respect and friendship between them six decades on from their sporting heyday. An unexpected stumbling block in the storytelling was the women’s modesty. “They belong to an older generation and are very, very humble,” says Faraut, explaining that they often brushed off their achievements and dedication as “normal”. As such, he had to think of new ways to “convey the magic of your protagonists to your audience,” he says. “But there was a paradox: they were also very confident. They said they didn’t fear losing against the Soviet Union, because they trained so much.”

Their initial reaction to Faraut’s interest in them as a non-Japanese filmmaker was surprise, replaced by relief and then pride as they realised that this piece would go deeper into the women themselves as subjects. This is the first film for which Faraut opted to meet his subjects. His 2018 John McEnroe feature, for instance, focused solely on McEnroe’s sporting prowess. This time his interest lay in the people, as much as the performance. “When I started to read articles from journalists in the ’60s and also from more recent academics, I really felt that they lacked their testimony,” he says. “I didn’t like the way people were writing about them. I was upset – these writers were pretending to speak in the name of women’s dignity and emancipation, but they were just placing them in the context of the home or as mothers. I wanted to give them the opportunity to tell their story by themselves.”