Bend It Like Barriers

Lounging on the sofa on Sunday I found myself watching Bend It Like Beckham again. It made me wonder: have things really changed for South Asian women in football? A deep dive into whether Jess Bhamra's fight is still a reality today.

By Sarah Chandra & Glorious

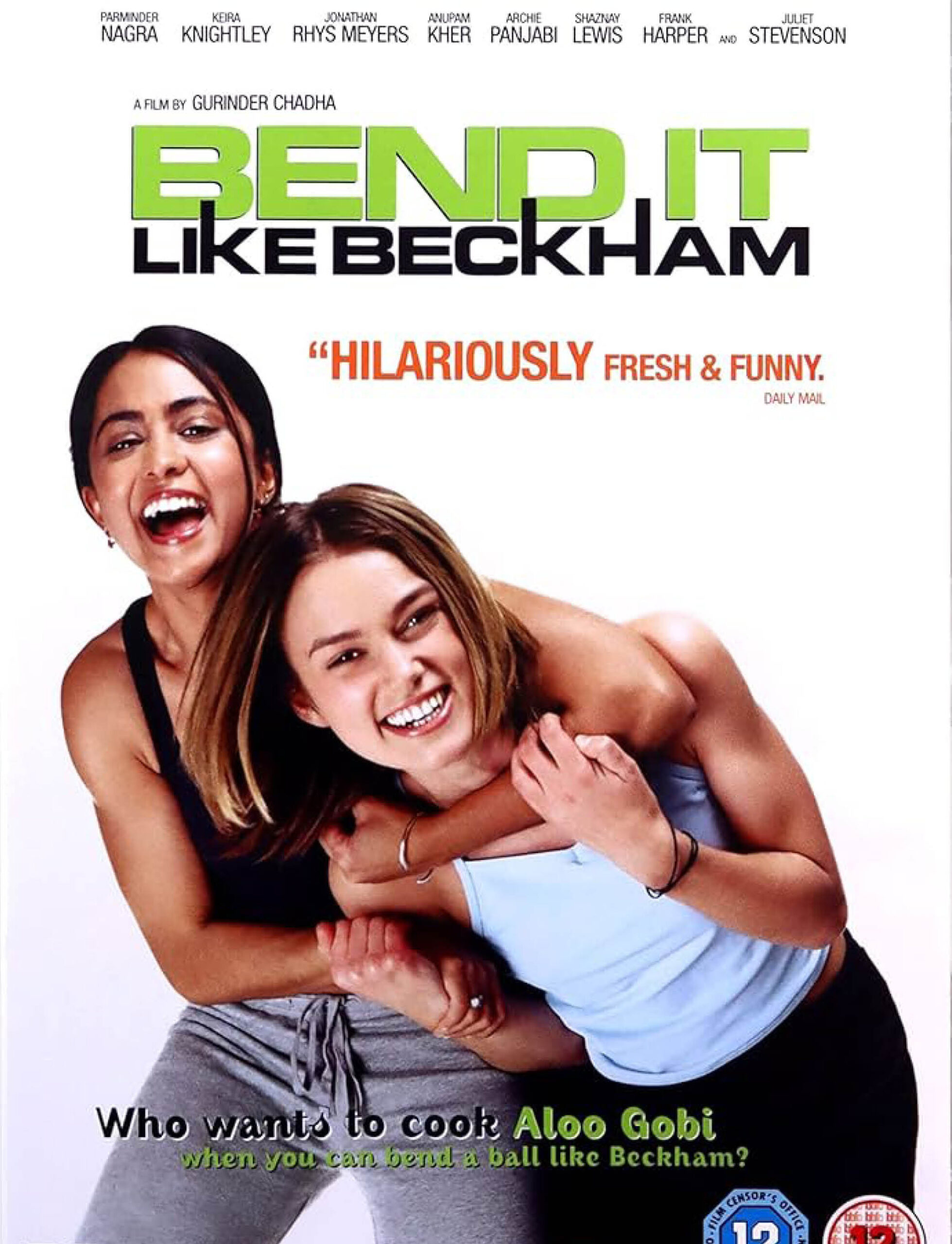

In 2002, a football sailed through the air on a cinema screen, curving improbably towards goal as a teenage girl in a turbaned Sikh wedding outfit sprinted after it. The scene was comic and triumphant – a young British-Indian woman quite literally bending the rules of tradition. Gurinder Chadha’s Bend It Like Beckham burst into British pop culture at a time when women’s football was barely on the radar for most people. It wasn’t just a sports movie; it was a feel-good call to ambition, an exploration of identity, and a playful kick at social barriers.

Audiences worldwide cheered for Jesminder “Jess” Bhamra (played by Parminder Nagra), the 18-year-old heroine who juggled corner kicks and cultural expectations, and many girls saw a piece of themselves in her story. On a modest £4.8 million budget, the film grossed nearly £60 million (Bend It Networks), proving that Jess’s fight to play football resonated far beyond her home town of Hounslow. For a generation of young women – especially those from immigrant families or minority backgrounds – Bend It Like Beckham was more than entertainment; it was validation that their dreams mattered, even if they had to dribble around a few prejudices to reach them.

So what made me decide to write about a film from 23 years ago? Last Sunday, I found myself sprawled on the sofa, eating Hula Hoops, trying to avoid hoovering the house or changing my pillowcases (because, honestly, who enjoys that?). Bend It Like Beckham came on, and before I knew it, I was hooked, glued to the screen as if it were 2002 all over again. I laughed in all the same places, teared up at moments I knew were coming, and for some reason, found myself Googling Keira Knightley’s hair bands.

I texted my friend, telling her to turn her telly on and watch along with me. We both loved Bend It Like Beckham when we were younger, and she loved it so much she developed a slightly alarming infatuation with Jonathan Rhys Meyers, which led to an ill-advised attempt to steal a copy of Heat Magazine from Tesco because he was on the cover. But that’s a different, somewhat traumatic story for another day. She texted back, ‘Still so good. Still love Jonathan. Still feel the same.’ More than just nostalgia and teenage crushes, her response made me stop and think- I still feel the same. Watching it again made me wonder, though: Has anything really changed? Is this still the same reality for young women from immigrant backgrounds, caught between cultural expectations and their own dreams? Have we truly moved forward, or are the same barriers still in place, just looking a little more polished? That’s why I’m writing this piece.

I grew up in a fairly religious immigrant household in London, my parents were relatively open-minded. Unlike Jess, I didn’t have to hide my interest in sports; my three brothers made it a normal part of life. But I saw the struggles in my friends’ experiences. Some faced cultural barriers, while others simply didn’t receive the encouragement they needed. Their parents weren’t necessarily against it, but they didn’t actively support it either. Football or sport in general wasn’t seen as a ‘serious’ pursuit for girls, particularly in immigrant communities where academic success often took priority. And if your dream wasn’t actively encouraged, was it ever really an option? I had friends who played football, hockey and netball at school but knew it wouldn’t go beyond that – not because they lacked talent, but because they lacked the pathway, the parental approval, the belief that sport could be a future rather than just a hobby.

Jess’s journey in the film is an uplifting one, but it’s strewn with conflicts that were instantly recognisable. She grapples with her parents’ expectations (they’d rather see her studying law and cooking a perfect aloo gobi) and her own passion for football. Ambition in a girl, and in a traditionally “male” sport, is portrayed as both admirable and subversive. The film uses humour to tackle serious themes: one moment we have Jess’s mother fretting that her daughter’s legs are bare in shorts (“What family will want a daughter-in-law who can run around kicking football all day but can’t make round chapatis?”), and the next we see Jess leading her team to victory with a curling free kick. That blend of comedy and social commentary sparked conversations in living rooms and classrooms alike. Suddenly, people were talking about why a girl’s love for sport might clash with cultural traditions, or why a mother might fear her tomboyish daughter won’t find a husband. By wrapping these themes in laughter and a great soundtrack, the film brought topics like gender roles, cultural identity, and even sexual orientation (remember Jules’s mum suspecting the girls were a couple) into the open. In 2002, that felt refreshing and even a little bold.

opportunity

While the film sparked important conversations when it was released, it left me wondering if things have truly changed. Is the experience of young South Asian women today any different from Jess Bhamra’s struggles on screen, or have the barriers just taken a different form?

At the time of the film’s release, the inequality between men’s and women’s football was glaring. Women’s football in England was essentially an amateur pursuit – talented female players had few avenues to go professional, and certainly nothing like the fame and fortune of Beckham. The film was painfully accurate in showing that Jess’s only real opportunity came from a scout offering her a scholarship to play in America. England had no equivalent system, no clear pathway, no real infrastructure to support women’s football as a professional sport. Back then, the Women’s Premier League was barely funded, games were played on subpar pitches, and even the best players often had second jobs.

Fast forward to 2025, and the progress is undeniable. The Women’s Super League is now fully professional, games are televised, and crowds are growing. The UEFA Women’s Euro 2022 final, held at Wembley, saw a record attendance of 87,192 spectators – the highest ever for any European Championship final, men’s or women’s (UEFA Official Report). The sight of a packed Wembley, roaring as the Lionesses lifted the Euro 2022 trophy, was a triumphant answer to anyone who once dismissed the women’s game. The 2023 Women’s World Cup was the biggest yet, and new generations of girls now have female footballing idols to look up to. Jess’s fictional journey no longer feels as far-fetched.

Yet, with all the cheering and record-breaking, it’s important to remember that not every barrier has been banished. The film’s feel-good ending – Jess flying off to America, parents won over, dreams intact – glosses over some of the harsher realities that persist even today. One of the biggest ongoing challenges is financial inequality. Women footballers still earn a mere fraction of what their male counterparts do. The average yearly salary in the Women’s Super League is about £47,000, compared to £8.2 million for men in the Premier League (Evening Standard). That gap is astronomical. If women’s football is truly valued now, why is the financial disparity still so vast? Why do many female players still have to hold down second jobs? Why is their career security so fragile?

More than twenty years after Bend It Like Beckham put a Sikh girl at the heart of a football story, South Asian women are still fighting to carve out space in the game. The film resonated because it captured a truth that remains relevant today: the love for football is there, but the path to the top is still filled with obstacles. Despite growing grassroots participation, South Asian women remain barely represented at the elite level. A 2024 investigation found that only 22 of the approximately 3,700 professional male footballers in England were of South Asian heritage, and the women’s game faces the same struggles (Sky Sports). The reasons are multifaceted – cultural expectations, financial barriers, systemic biases in scouting, and a lack of visible role models all play a part in limiting opportunities for South Asian women to progress in professional football.

What does it mean to be a South Asian woman in football? The answer is not simple, because South Asian identity is not a monolith. One of the biggest issues in discussions about representation is treating South Asians as a single, uniform group. While “South Asian” broadly refers to people with heritage from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, and beyond, these communities are distinct, each shaped by different cultures, languages, religions, and histories. The South Asian diaspora in the UK includes Punjabis, Bengalis, Gujaratis, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Sri Lankans, and Nepalese, all of whom have different relationships with sport, influenced by factors like family expectations, religious beliefs, and societal attitudes. While these communities share some common experiences, their barriers to participating in football are not identical.

Despite these differences, South Asian women face shared structural challenges in football. Visibility is one of the biggest. South Asians make up around 9 percent of the UK population, but their presence in professional football remains disproportionately low. A 2022 FA report showed some progress at the grassroots level, with male and female participation rising to 15.4 percent, up from 13.5 percent in 2021. However, representation at the elite level remains stubbornly low.

Religion plays an important role in shaping access to sport for South Asian women, but its impact varies across communities. Muslim, Sikh, Hindu, and Christian women all face unique challenges, yet they share many common struggles. Cultural expectations, family attitudes, and societal norms influence their ability to pursue football, but the barriers often stem from the same structural issues: gender, cultural norms, and a lack of encouragement for girls in sport.

balancing

For Muslim women, challenges often revolve around dress codes and the need for gender-segregated spaces. Nouhaila Benzina made history in 2023 as the first player to wear a hijab at a Women’s World Cup, demonstrating that faith and football can coexist at the highest level. However, for many British Muslim women, balancing both remains difficult. The Muslim Women in Sport Report found that 80 percent of British Muslim women participate in sport casually, yet only 9 percent reach a competitive level. Nearly half (43 percent) cited unsuitable sports facilities, and 33 percent mentioned negative past experiences as barriers. Many would attend women-only sessions if available, but concerns about male staff and lifeguards persist (Muslimah Sports Association).

Sikh women face similar barriers. A BBC report revealed that fewer than 30 percent of Indian women participate in any sport, despite nearly three-quarters of Indians believing sport is important in daily life. While Sikh men are increasingly visible in football, Sikh women remain largely absent at all levels. Cultural expectations around education and career often take precedence over sport. Kira Rai, a Sikh-Punjabi winger for Derby County, has spoken about the importance of being a visible role model for young girls who rarely see themselves represented in football. While her family was supportive, she recognises that for many South Asian women, football is still seen as a hobby rather than a career.

For Hindu and Christian South Asian women, the barriers are often more cultural than religious. In many households, academic success takes precedence, and sport is not seen as a viable career. Millie Chandarana, former Blackburn Rovers player now with Nottingham Forest, is of dual heritage – her father is Indian and her mother English. She has said, “There wasn’t anyone to look up to, to have a role model. Growing up, there were only a handful of players who had professional contracts.” Asmita Ale, a defender for Leicester City, made history at 18 as the first Nepalese footballer to sign a professional contract in English football. She explained, “I know some Asian parents wouldn’t be like that because their heads are more educational, which my parents are too, but they really supported me.”

Family attitudes remain a key barrier across all communities. In many South Asian households, education is prioritised over athletics, and football is rarely seen as a viable career. A 2022 Active Lives survey found that 100,000 girls had taken up football more regularly since 2017, yet a gender activity gap persists. Boys are 5 percent more likely to be active than girls, and the gap is even wider among South Asians at 10 percent. Without family or community support, many talented South Asian girls struggle to continue playing beyond school level.

Beyond the pitch, South Asian women also face a lack of representation in coaching, management, and leadership roles. Manisha Tailor MBE is one of the few breaking this barrier. As the youth manager at Queen’s Park Rangers, she is part of a group that makes up fewer than 3 percent of coaches, volunteers, and referees from an Asian background. She is also the only South Asian woman out of 92 professional English football clubs to hold a full-time coaching role in men’s professional football (FA Asian Inclusion Plan, 2022).

The FA has acknowledged the problem, launching the “South Asians In Football’ initiative, aimed at increasing visibility and opportunities at all levels of the game. But the question remains: will this initiative lead to real change, or will it be another well-meaning attempt that fails to address the deeper structural issues?

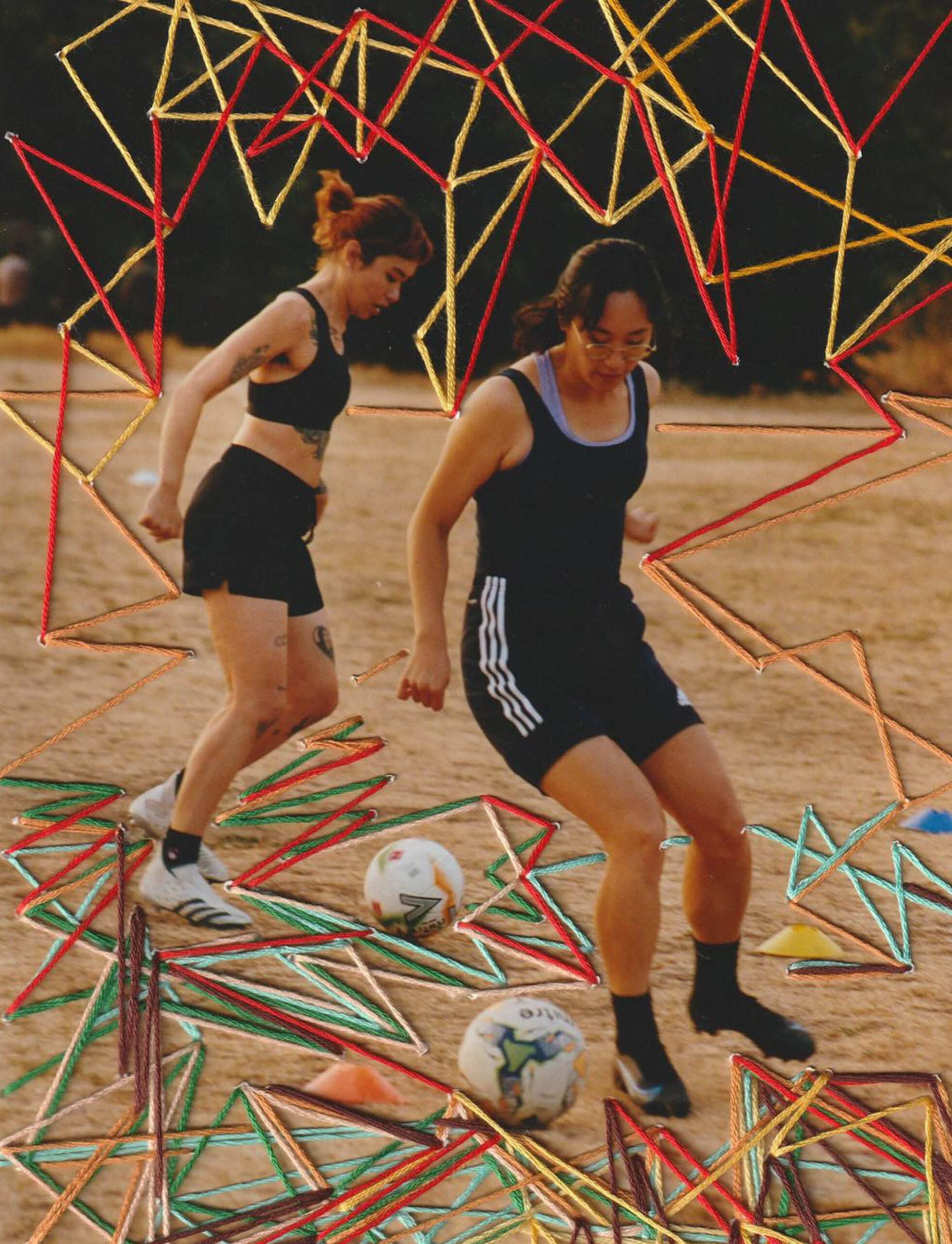

Change is happening, but progress remains slow. At the grassroots level, more barriers are being removed, and safe spaces are being created where South Asian women and non-binary people can find community within football. Community is central to all of this. Initiatives like Sisterhood FC and Baesianz FC are not just about playing the game; they provide a sense of belonging- a space where cultural identity is embraced rather than treated as a barrier. Sisterhood FC caters specifically to Muslim women, ensuring modest dress and community values are accommodated. Baesianz FC, co-founded by our Glorious friend, artist Nicole Chui (read her Glorious story here) is open to all Asian women and non-binary players, focuses on inclusivity in a sport where Asian representation is still lacking. These grassroots teams show that when the right environment is created, women do show up, play, and thrive.

grassroots

If we truly believe in representation, it is not enough to celebrate the occasional success story. We must remove the barriers that keep so many others from following. That means more investment in grassroots football, tackling biases in scouting, and ensuring football is a genuinely inclusive space. Progress is not just about seeing a handful of South Asian players in the game – it is about making sure that the next generation of South Asian girls who love football can pursue their dreams without facing these same obstacles.

So, what now? Bend It Like Beckham remains powerful because it still reflects the reality faced by South Asian women in football. Women’s football is bigger than ever, but still undervalued. Girls today have more opportunities, but still have to fight for them. Representation has improved, but systemic barriers persist. It is not enough to celebrate progress. We must demand more. More pay equity, better grassroots investment, and broader inclusivity. These are not radical ideas, but necessary ones.

Ultimately, Bend It Like Beckham was never just a film about football. It was about a girl carving out her own space in a world that was not built for her. Watching it in 2025, I want to believe that things have changed, that no young woman has to fight for permission to pursue what she loves. But for too many, the fight is not over. It has simply taken a new form. Maybe that’s why the film still resonates. It challenges us to go further. It’s not just nostalgia that keeps us coming back; it’s the unfinished work, the ongoing fight, the dream that still needs pushing forward. The final message remains: keep going, keep bending the rules, breaking the mold, and pushing past every “no” until the game is truly open to all. Because if Jess Bhamra taught us anything, it is that no dream should be out of reach – neither in football nor in life!

As ever, let us know your thoughts over on social- @glorioussport

Watch Bend It Like Beckham:

Title image credit: Christine Parry/Fox Searchlight