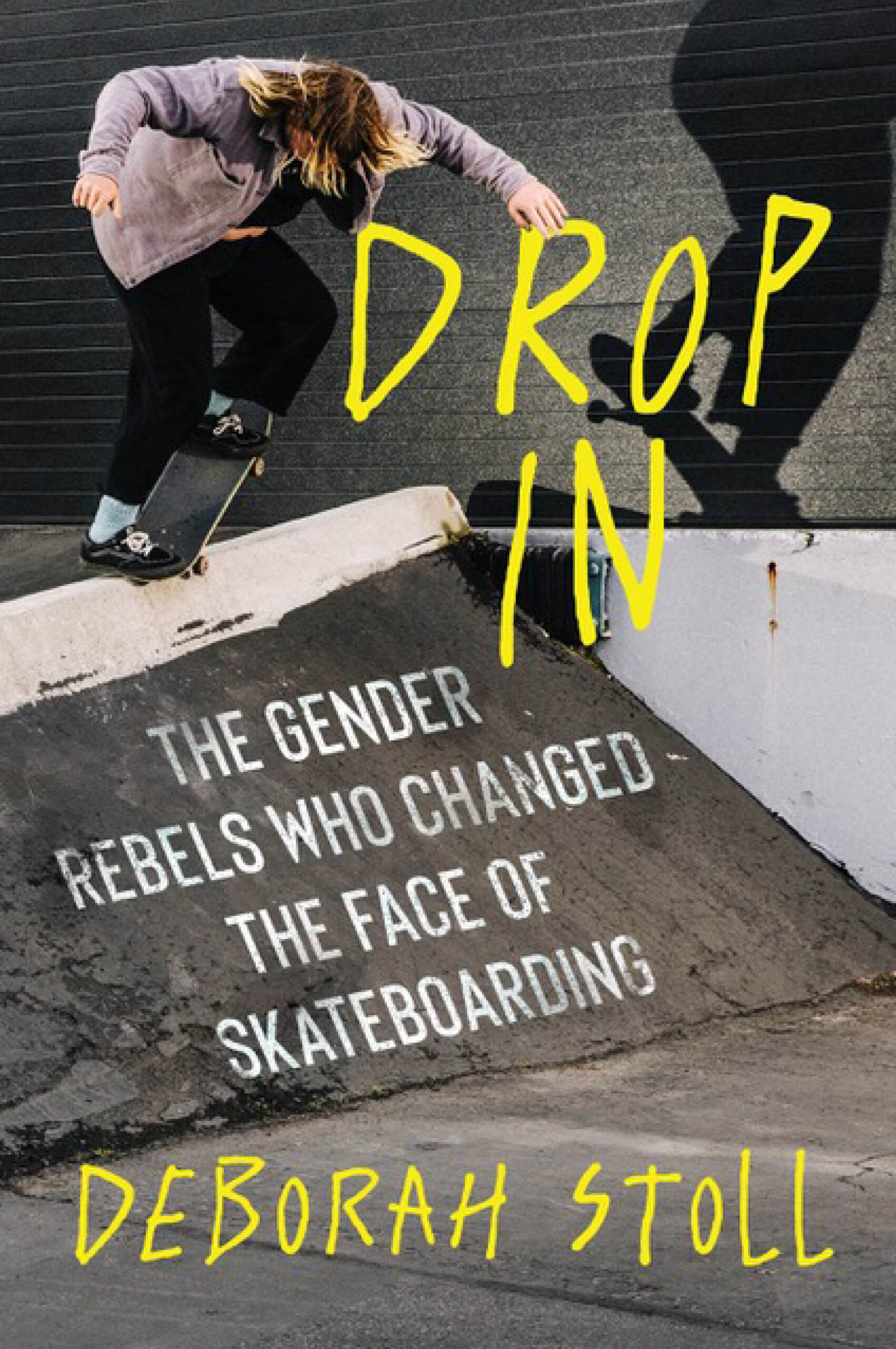

Drop In

Discover the untold stories of the female, queer, bi, and non-binary athletes who revolutionised skateboarding in this excerpt from Drop In – the groundbreaking new book that celebrates their ferocious courage, determination, and flair for their sport.

By Deborah Stoll

Ever wonder what happens when a group of trailblazing female skateboarders hit the road for an epic adventure?

In this excerpt from Deborah Stoll’s new book Drop In, you’ll join legendary Vanessa Torres, Amy Caron, Jaime Reyes, and Lauren Mollica as they embark on the first-ever all-women’s skate trip to Australia, navigating the highs and lows of pushing the boundaries in a sport long dominated by men.

Drop In is the first book to tell the story of the female, queer, bi, and non-binary skaters who defied expectations of gender and talent and blazed a path to today’s more equitable skate culture. Set against the backdrop of the 2021 Tokyo Olympics where skateboarding made its historic debut, the book follows the lives of four main skaters:

· Alana Smith: the first openly nonbinary athlete in Olympic history

· Vanessa Torres: a record-breaking runaway

· Marbie Miller: an accidental boundary-breaking trans icon

· Victoria Taylor: the skate rookie turned social media sensation.

With deep dives into sports history, gender studies and social justice, Drop In offers a fresh perspective on skateboarding, celebrating the courage and resilience that have shaped the sport today. ‘Drop In’ to this excerpt and get a taste of their unforgettable adventure!

“Call me Mom,” said a burly bearded man in pigtails dressed in a black polka-dot skirt and yellow button-down shirt. It was February 2003, and Vanessa Torres, Amy Caron, Jaime Reyes, and Jersey-born pro skater Lauren Mollica were waiting to board a plane to Australia for an all-girls skate trip. It would “last more than a week but less than two weeks, and start in either Melbourne or Sydney and end at the Globe World Cup Skateboarding competition,” explained Big Brother editor in chief Dave Carnie, aka the burly bearded man in pigtails.

The skaters knew where they were going and what they were going there to do as they boarded the plane, but they hadn’t known Dave would be joining them so he could write an article about the trip for Big Brother—a magazine run by self-professed “high- level functioning pieces of shit.” Their motto was “You can’t write about skateboarding, and anyway who gives a fuck?” Issue 1 hit the streets slapped with a warning sticker that read due to the fact that no one here had any idea what in the hell they were doing, this issue has been declared a total failure.

Issue 2 became a sleeper hit thanks to its proliferation of boobs, butt cracks, full-frontal, and QUESTIONS WRITTEN IN ALL CAPS LIKE THE INTERVIEWER WAS YELLING AT THE INTERVIEWEE.

“Reading back through some of this stuff, I would change a lot of the language,” Dave said. “But what we were doing was tongue- in-cheek. We were reflecting the attitudes that were in our culture back then, exaggerating the stereotypes to show their stupidity.” Which explains why, despite the magazine’s misogynistic, prepubescent modus operandi, Big Brother were supporters of, and advocates for, girl skaters.

“As Mike Vallely said, ‘No one gave a shit about them, people openly tried to make them feel bad in skate parks, and they got no respect from the skateboarding industry,’” Dave said. “We [Big Brother] also felt that way. We didn’t get respect from mainstream culture or from the cities that we lived in, so we could appreciate their situation.”

The “girl skaters” were unaware of Big Brother’s simpatico, so while they thought being featured in Big Brother might be amaz- ing, they thought it might also be really bad.

“We were so stoked, but nervous, ‘cause, like, what’s he going to do to us?” said Amy. “Everyone featured in Big Brother got the piss taken out of them.”5

The only person who seemed unconcerned was Jaime, who’d chosen a seat by herself in the back of the plane, arms crossed, eyes at half-mast, wishing the tour was already over. “I was a little weirded out,” she said later. “I don’t know if I’m gonna get along with these girls, you know? I’m, like, a difficult person, I guess.”

But getting along with Vanessa and Amy could prove chal-lenging to anyone. “The Evil Twins,” as Jaime called them, were always talking smack to journalists, throwing food at each other, plotting in faux whispers, fighting at exaggerated decibels, and drinking vodka Red Bulls, which got them super drunk and super amped in one fell swoop.

advocates

“Everybody knows to watch out when we’re around,” Amy said. “Either something’s going to go wrong or we’re going to start trouble.”7 The only good thing Jaime could say about the Evil Twins was Vanessa dressed better now, even if she looked like Amy’s mini- me, both of them in oversized button-ups, baggy jeans, brown hair pulled back in low ponies. “She’s like the Grinch,” Amy whispered to Vanessa. Vanessa shrugged. “Probably one day she’s going to be really nice.” Jaime pulled her Supreme hoodie over her ears to block out their voices. “Don’t hold your breath,”8 Amy said.

After landing in Australia, the Gallaz crew picked up three more skaters—Rookie Skateboards team rider Jessie Van Roechoudt (commonly known as Jessie Van), local Aussie Monica Shaw, and New Zealand’s Georgina Matthews. They packed everyone into a dual-row, bench-seat Econoline and off they went! Fights between everyone broke out daily, petty aggravations exacerbated in no small part by the lack of personal space, median 90-degree temperatures, and perpetual hangovers. When they weren’t fighting, they were chasing koalas, peeing in water bottles, spray-painting their shoes because no one liked their colorways, and, of course, skating. Rails. Ledges. Mailboxes. Tables. Tables on stairs. Ramps on the ocean. At a demo in the tiny coastal town of Ballina, the entire community turned out to watch them crush the course.

“After the girls finished, all the guys were trying to do it and they’re falling over.” A female spectator laughed and pointed to a bunch of local boys standing around looking ashamed. A Viking with a long red beard and white T-shirt that said i yam what i yam! gave the event an exuberant two thumbs up. “Brilliant!” he said. “That was too much. The girls killed it. Absolutely killed it.”10 Everyone signed the back of his shirt as he raised his arms in victory.

“Particularly Amy and Vanessa got really good, really quick,” said Mike Hill, one of the film’s directors. “As far as everyone getting out there and skating and engaging no matter what shape they were in, they did it. And that doesn’t always happen with the guys. That’s what I call professional, as far as skateboarding goes.” Speaking of professional . . . The last morning of the tour, bobbing on the waves of a collective hangover, the crew slouched into the 14,820-seat Rod Laver Arena for the Globe World Cup Skateboarding contest. “Super mad my daughters have to get up at six in the morning and compete!” Dave yelled to anyone in earshot. “They’re pirates!” he cried tangentially. “I was surely not quite awake and probably not entirely sober, but I do remember being concerned about female skateboard contests for the first time in my life,” he said. “Girl skaters get the worst times to practice, and the course is only open to them for fifteen minutes.”

All of this was old news to the girl skaters—getting fifteen minutes or no minutes at all before a competition to feel out the course to see if the ground is sticky or smooth, if the obstacles are steep or gentle, if there are cracks or rocks or candy wrappers your wheels can catch and flip you on your ass—but it was an eye- opener for Dave. For the first time ever, he wasn’t just listening to how hard it was to get zero practice time on a course you’d never skated before, then jump on it and compete at 8 a.m. when no one was watching. He was there. And he was watching. And he cared. And it sucked.

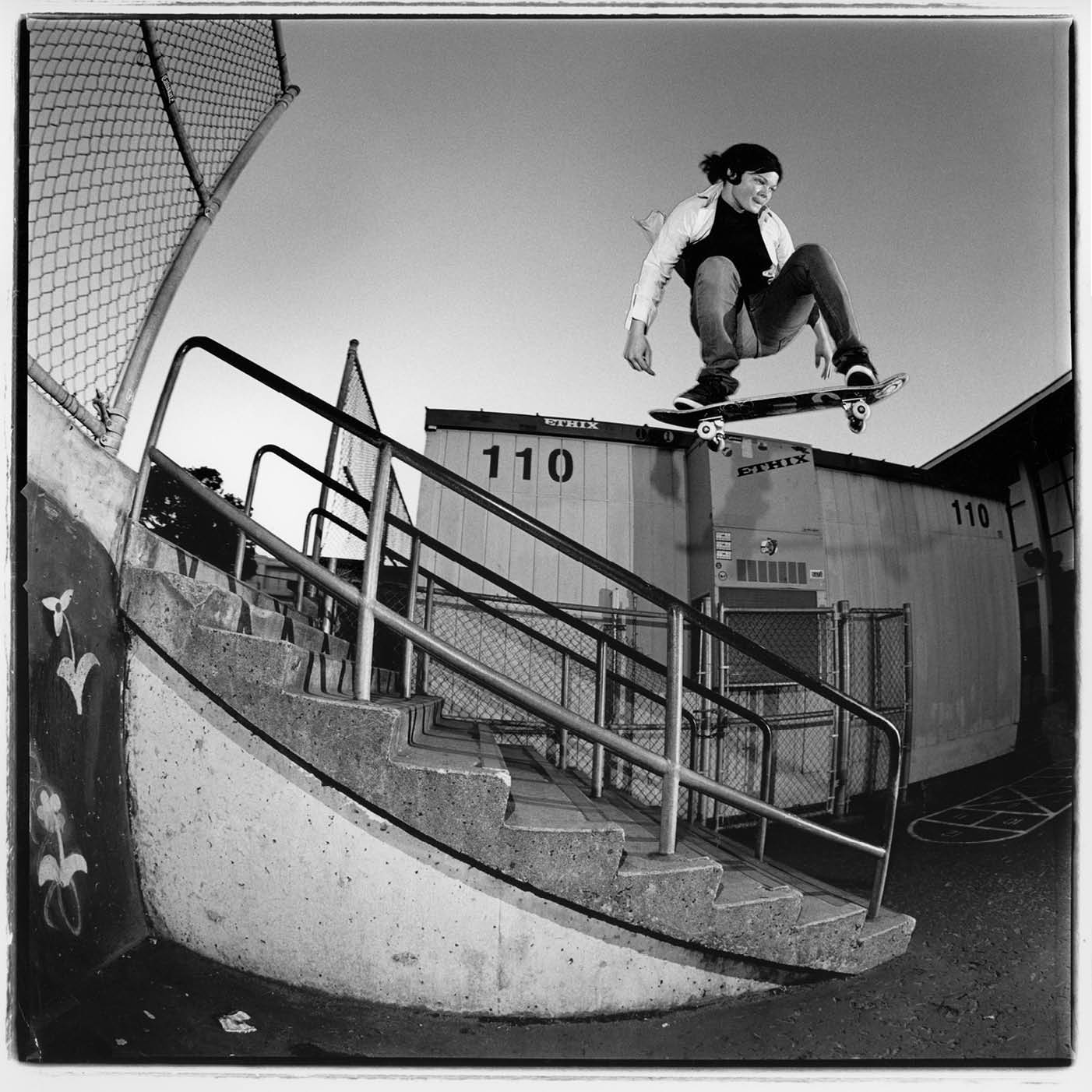

As people started filing into the stadium, Jaime dropped in. The right leg of her Diesel jeans hiked up bike messenger–style. She wore a Rookie T-shirt. White Louis Vuitton belt. Cruised around the course like a kid in high school who doesn’t give a shit what anyone thinks. Midway through her run she fell and took a moment to lay on her side with her head in her hand, her other hand on her hip, striking a pose.

“If I place, I place, if I don’t, I don’t.” Jaime shrugged. “As long as I go out and represent, that makes me happy.” “Next up, Monica Shaw!” said the announcer. “She’s ranked number one in Australia.” After skating all week with the girls from America, Monica didn’t feel like number one, and her performance proved it. “I was just dropping in, freaking out,” she said. “I let it get the better of me, the whole nerve thing.” And then: “The number-one ranked skater from World Cup Series last year,” the announcer crowed. “She won every event last season—Vanessa Torres!”

In her oversize black polo and baggy jeans, cuffs threatening to spill over her puffy shoes, Vanessa ollied onto a box, her arms pushing upward as she frontside 50-50’d a wide ledge, and then her left forearm spun around twice before she flew off, strictly horizontal to the ground.

STOMP!

Her body so low she could set down her palm. Kickflip, fakie. Kickturn, frontside 50-50 to flat ground. Pat a phantom dog’s head. Forty-two seconds in, Vanessa set up for a board slide, but her body was tilted too far forward, and when she tried to course correct her arms flew out behind her, pulling her too far the other way. She landed on her back.

There was something messed up on the rail, some kind of bump or something. Vanessa was trying to warn Amy to avoid it but Amy just kept laughing at her until it was her turn to go. Where Vanessa was all propulsive energy, Amy skated like she was sneaking up behind you to steal your wallet. Twisting her torso back and forth on the handrail like she had all the time in the world. Kickflipping up the gap like she could jump higher if she wanted to put more energy into it, but, nah. She hit the quarter-pipe and jumped over a hip like it wasn’t a competition, but that was just a smoke screen. Everything was a competition. And that time she won: $2,000 and a Ford Ka.

Following the women’s contest the men competed. Bucky Lasek took first and was awarded $10,000 and a Ford F-250. That’s an $8,000 cash difference and an approximate $20,000 trade-in variance for skating the same course, in the same contest, on the same day, while being a different gender.

propulsive

When Dave’s BiG Brother article dropped, it went on for pages about his friend pro skater Kenny Hughes’s terrible Australian accent, the tragicomedy of being a “deadbeat mom,” and the joys of petting kangaroos. It took a page and a half for the word “skateboarding” to appear, and when it did it was simply so Dave could explain that he hadn’t talked about it because he found all the other stuff more interesting. Like all Big Brother’s best exegeses, the article was a subversion of readers’ expectations—hot girls skating!—and instead was filled with veritable nonsense and a portrait of Dave surrounded by a crew of girl skaters who scared him so much he preferred “stapling my nuts to my legs and doing every stupid stunt in Steve-O’s repertoire to avoid mingling with them.”13 Okay, readers wanted to know, but could the girls hang? “They were as punk rock, if not more, than all the guy skaters out there,” Dave wrote. “Rude in restaurants, whining on the road, and ripping in the streets. Hanging out with them dispelled every girl skater stereotype I’d been carrying around in my head.”14 “Dave looked at us as equals,” said Amy. “Rolling with him gave us a lot of street cred. And he came and watched our contest and I don’t even know if he watched the guys even though he knew all those dudes. His mission was being there with the girls, which was super cool.”

The coolest thing about the trip, though, had to be the skaters’ progression. If there’s a holy grail in skateboarding it’s progression—a skater’s willingness to constantly evolve—and skate trips, like any other kind of immersive experience, are progression accelerators. Whatever you’re into, whether it’s art or music or writing, when you spend day after day doing that thing with a group of other people doing that thing, you’re going to advance exponentially faster than practicing that thing alone, in short spurts. And it’s not just the consistent doing of the thing that matters, it’s being surrounded by a community of like-minded people. It’s learning from each other and encouraging each other, and engaging in conversations about the minutiae of your communal obsession.

“The first moment I realized I wanted to be a pro skater was at an all-girls night at the Berrics,” said pro skater Samarria Brevard. “We literally didn’t stop skating until four o’clock in the morning, and then we slept in sleeping bags on the ramps. I came home from that and I was like, Alright, I don’t want to play basketball anymore, I just want to skate.”

Which is exactly what makes these trips so important— they’re proof positive that your art doesn’t have to be “a phase,” but could become a meaningful pursuit. Given the opportunity to talk about perspective and palette techniques with other painters; making music for the first time with other musicians; pumping on a ramp next to someone, intuitively in sync, flying higher and higher until you both touch the coping, these shared experiences are what keep you alive when the reality of being an artist feels untenable. While the Gallaz tour was just one trip, it’s notable that given the time, money, and means, this riotous group of girl skaters confirmed that they could throw down no matter how early or how hungover, commune, rip, and progress. But while tours for pro male skaters continued to be commonplace, that was not the case for women. Why? What was the issue? “If you look at traditional [skateboarders], by which I mean cis men, they don’t think about any of this because they’re the dominant majority,” said Jessie Van.

By and large, injustices in the world aren’t taken to task unless someone has a vested interest. Which is understandable. There are a billion issues to rally around—there’s the environment to save, cancer to cure, animals to rescue—one person cannot fight for everything. What someone typically goes to the mat for, then, is something that directly affects them. Women not having the same opportunities as men didn’t actively affect the men them- selves, so it didn’t register as a problem. And in 2003, none of those men were old or mature enough to have daughters, whose actualities often have a profound effect on new fathers, i.e., what was I thinking? Women are fantastic! But there was Dave Carnie, a man without offspring, who boldly took up the mantle “Mom,” and got an unexpected taste of (some of) the inequities of being a girl. “That was one of the most rewarding skate trips I’ve ever been on,” Dave said. “It was really funny and made for great content, but at the same time I learned a lot.” If only every girl skater had a Big Brother.

This excerpt from Drop In: The Gender Rebels Who Changed the Face of Skateboarding by Deborah Stoll (Dey Street Books, 2024), appears by permission of the publisher.

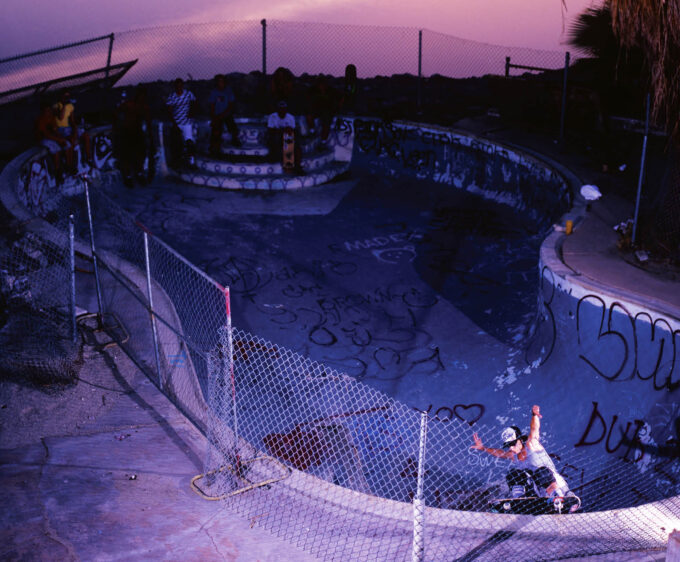

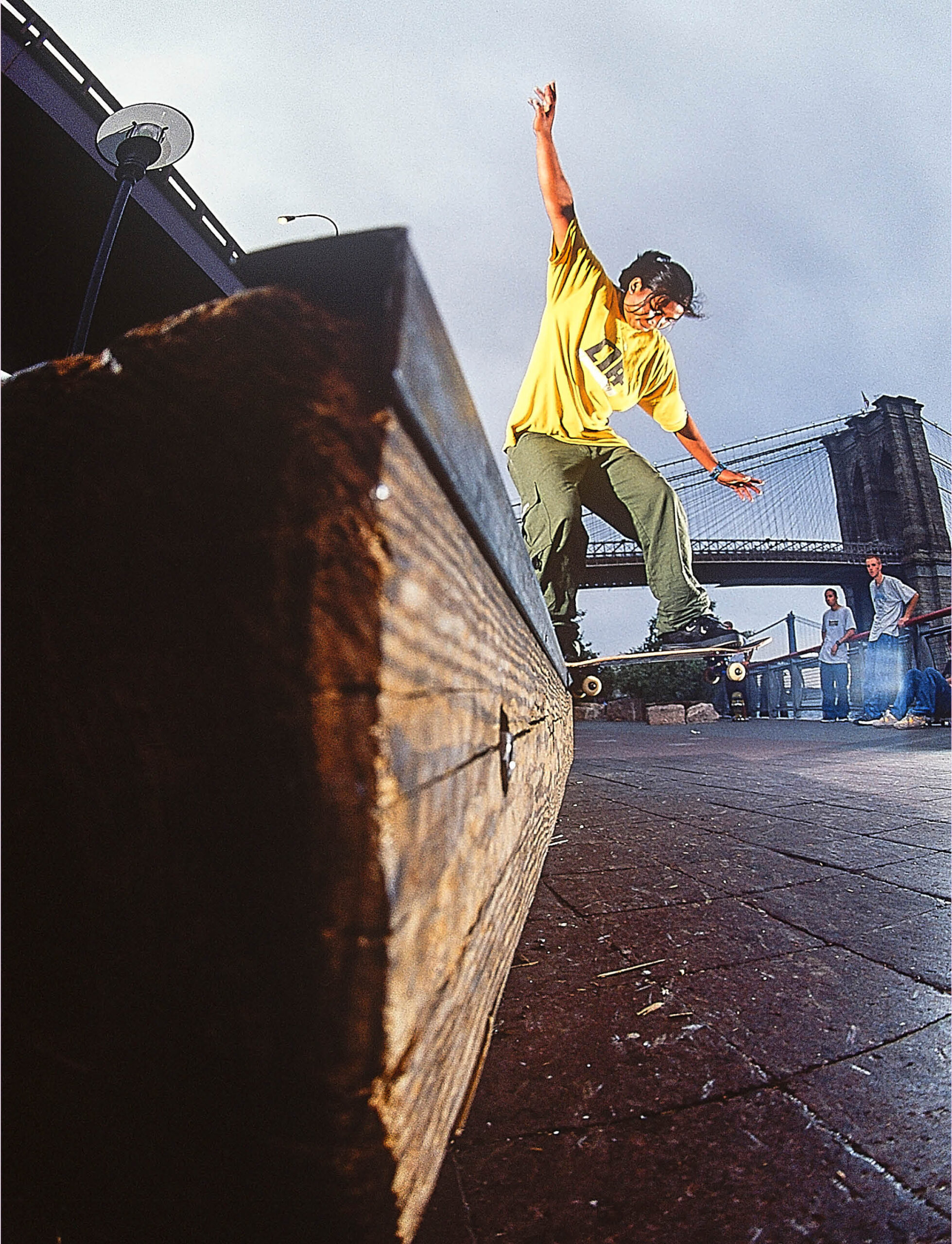

Title Image featuring Cara-Beth Burnside by Brian Fick