Is My Paralympic Admiration Problematic?

Sport is sport, athletes are athletes. But I’ve been questioning if my admiration for Paralympians carries a hint of patronisation. Are societal attitudes clouding how we truly celebrate their achievements?

By Isabelle Smith

There’s something about LimeBikes that drives me mad. It’s not just their tendency to be abandoned haphazardly across the pavement, as if gravity had decided to take a vacation, but also the disregard they show for pedestrians who truly need a clear path. As an able-bodied person it’s irritating enough when these bikes block my route to the coffee shop, but what truly angers me is imagining how my Blue Badge holding father, who’s been on crutches for ten years following a botched back surgery, would struggle to navigate around them. The thought of him having to dodge these obstacles, especially when they force him to manoeuvre around large curbs into oncoming traffic, underscores a broader issue: a lack of consideration for those who face daily challenges just to get by.

Last week, as I was making a glamorous trip to the shop to buy bin bags. I could barely contain my frustration when I saw a young man, probably in his early twenties, propping his LimeBike up right in the middle of a narrow pavement and beginning to walk away. I couldn’t help but confront him. “Are you seriously leaving that there?”, I asked. He barely looked up from his phone. Trying to keep my cool but clearly irritated, I added, “Just move it 20 metres up the road to the LimeBike docking rack thing! People need to walk here. What if I were in a wheelchair?”.

He finally looked up, his face a picture of youthful arrogance, and replied, “Why do you care? You’re NOT in a wheelchair.” My blood was boiling, and while I wanted to come up with something clever and impactful, all I managed was a frustrated “Wanker!” shouted at the back of his head as he continued to walk down the street.

As the Paralympics began, that arrogant man and his poorly-fitted suit kept coming to mind. I hoped he was watching. I wanted him to see these athletes—people with no limbs, people with limited vision, people in wheelchairs—facing challenges he likely couldn’t even imagine, competing on the world stage with a strength and resilience that far exceeds his understanding. I wanted him to realise that these Paralympians weren’t just overcoming their disabilities; they were, quite simply, excelling.

Yet every time I sat down to watch the Paralympics, I couldn’t shake an uncomfortable feeling. I work in sports media and have a relatively solid grasp on the world of sport; some might even say I am somewhat knowledgeable. Still, I find myself questioning how I talk about the Paralympics. Am I being patronising? Am I one of those people who say things like, “They’re incredible, considering their disabilities”? Am I unknowingly, unconsciously, being ableist?

I’ve wrestled with these questions daily since the Paralympics started, as I sit in front of my TV cheering on the competitors. Am I putting them on a pedestal not because of their athletic achievements, but because they’re competing despite their disabilities?

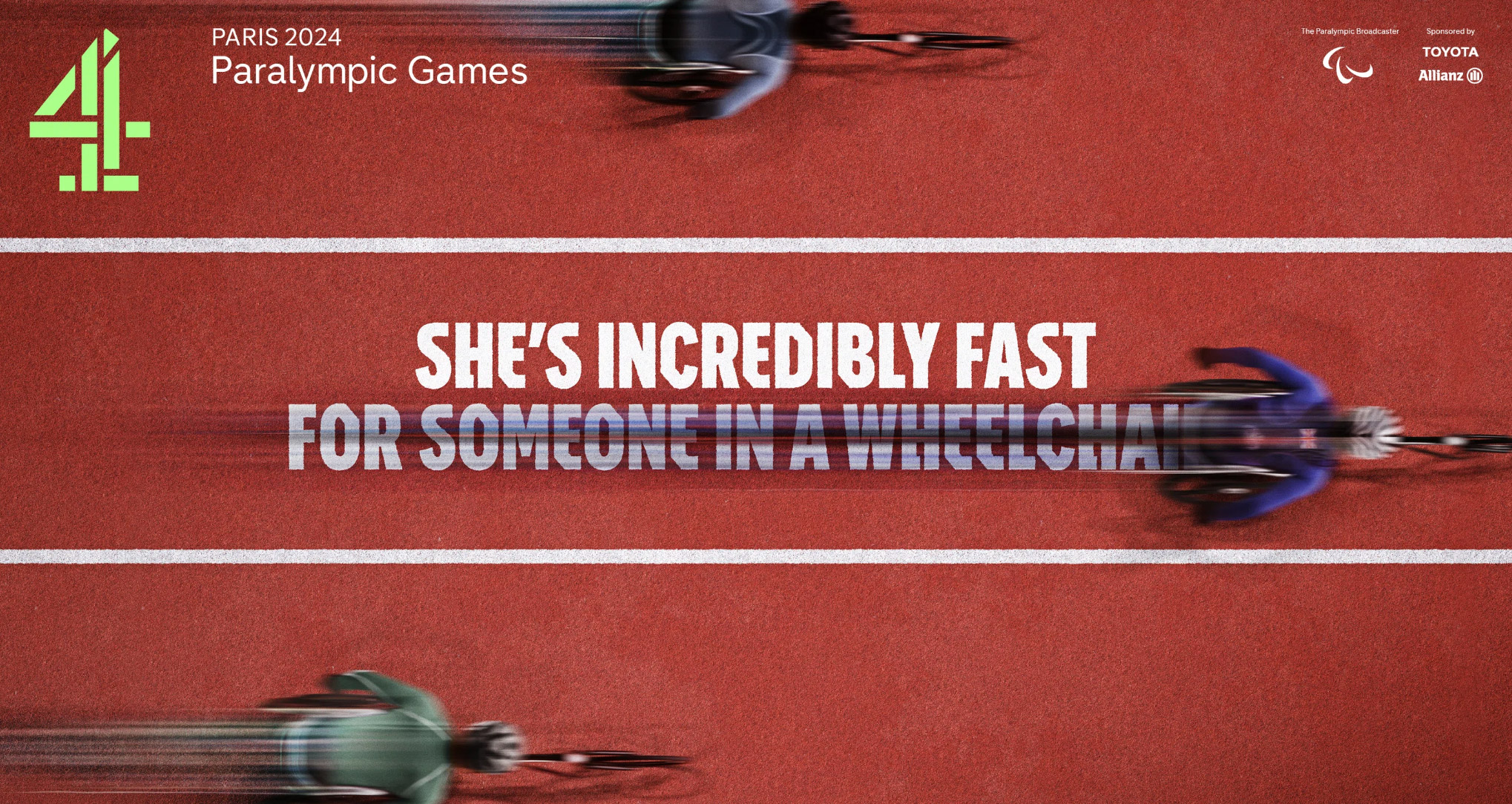

Channel 4’s latest campaign for the Paris 2024 Paralympic Games strikes at the heart of this issue. Their film, Considering What?, (watch here) challenges viewers to see Paralympians for what they truly are: elite athletes, no different from their Olympic counterparts. They’re not overcoming their disabilities; they’re overcoming the same forces that every athlete battles—gravity, friction, time. The campaign’s message is clear: stop patronising Paralympians by seeing their disabilities first and their athletic prowess second. According to Channel 4’s research, “59% of people said they watch the Paralympics to see athletes overcoming their disabilities. Only 37% watch for the pure thrill of the competition” (Channel 4, 2023). That’s a stark contrast, isn’t it? It shows just how deeply ingrained these patronising attitudes are. The Paralympics shouldn’t be about watching people “triumph over adversity”; it should be about celebrating some of the best athletes in the world, full stop.

I discussed this with my friend Maud, who has been a part of my life since we were children. Maud is probably the most intelligent person I know and ever will know. She exudes a unique blend of academic chic mixed with a touch of Sophia Loren glamour, though she speaks in a sultry, husky South London accent. What else can I tell you about Maud? She’s a devoted mother of two, a brilliant goal defence in netball, a fantastic party planner, and she’s hilariously allergic to my so-called ‘hypoallergenic’ dog (though I think she’s being a bit dramatic). Oh, and she’s missing an arm—she lost it in a childhood accident. Despite this, Maud refuses to be defined by her disability. It rarely even comes up in conversation. When it does, it’s usually because someone is staring at her in the pub, watching in disbelief as she carries two pints back to our table as if it’s the most ordinary thing in the world.

achievements

“What are you on about?” she laughed when I shared my concerns. “You’re not patronising. The issue isn’t you—well, not just you—but how people react when they think someone is ‘different.’ That’s what’s frustrating.” She’s right, of course. It’s that subtle shift in tone, that moment when someone’s voice softens as they realise they’re talking to a person with a disability, as if they need to tread carefully, not offend, not point out the obvious. It’s like when people see my father’s crutches and suddenly start speaking to him louder, as if his hearing has somehow deteriorated along with his back.

Research aligns with this point of view. Studies suggest that these small, often unconscious actions contribute to what Rosemarie Garland-Thomson describes as “the cultural scripts of disability, where the disabled body is seen as vulnerable, dependent, and in need of special treatment” (Garland-Thomson, 2002). It’s a widespread issue, deeply ingrained in how society perceives disability.

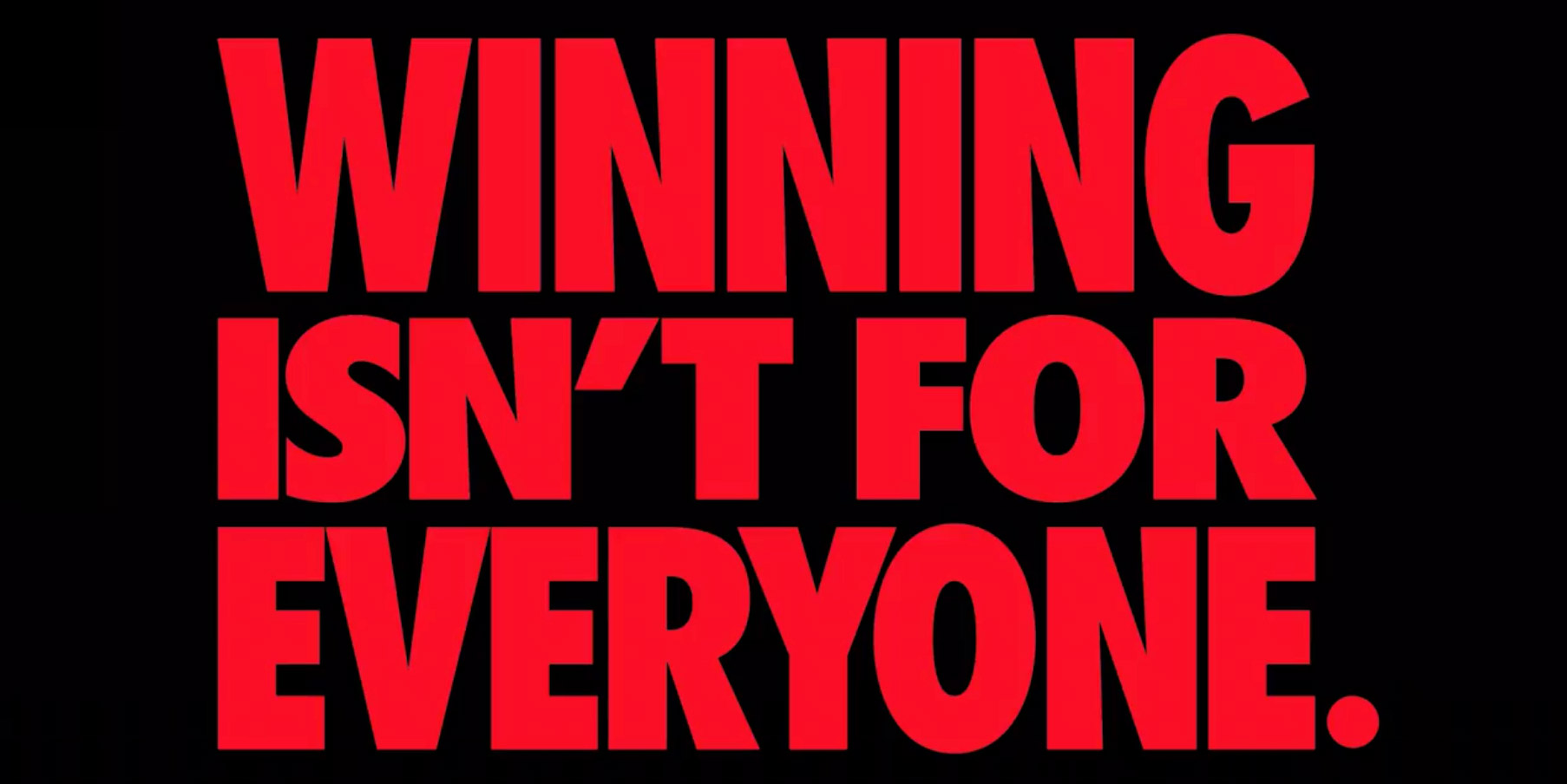

Nike’s recent ‘Winning is Winning’ ad (watch here) campaign for the 2024 Paralympic Games also tackles this issue head-on. The 30-second spot, set to a soaring Beethoven soundtrack, features a narration from renowned wheelchair fencer Bebe Vio. “They say that just being here is winning—participating is winning,” Vio asserts in the commercial, over quick-cut scenes of Paralympians in the throes of fierce competition. “Last time I checked, winning is winning.” The ad is designed to “celebrate the incredible achievements of Paralympic athletes and redefine the essence of victory,” showcasing athletes who “break barriers and challenge perceptions on the world stage” (Nike, 2024).

Richard Glennie, founder of Woven and ex-EMEA Communications Director of Running at Nike, advised that one of the brand’s founding principles, ‘If you have a body, you’re an athlete’, places emphasis on equality, telling me, “The brand has another maxim; ‘Always listens to the voice of the athlete’ to ensure the stories it tells are authentic. Since the brand’s 2020 Global Innovation Summit, which was a springboard to discussing ways of shaping the future of sport to support different athletes and engage in discussions to shape existing and forthcoming product innovations, such as Flyease. As such, there’s been a concerted effort to represent Para athletes more equally, and afford them the opportunity to share their views. It explains why Nike is always at the forefront of product innovation – We’ve got to show up for all athletes, not just in the Olympic year!”.

And here’s the thing—these Paralympians, with their prosthetics, their wheelchairs, their incredible resilience, could likely do what most able-bodied people couldn’t. They could lift a LimeBike off the pavement and hurl it across the street without breaking a sweat. They could navigate those narrow pathways that I find myself stumbling over in. They could outlast, outplay, and outshine in a way that leaves no room for patronising pity.

Still, the question remains—how should able-bodied individuals like myself talk about the Paralympics and disability in sport? How do we avoid sounding ignorant or, worse, like we’re trying too hard to say the right thing? It’s a minefield, but perhaps the answer isn’t in overthinking every word we say. Maybe it’s in changing the way we think about disability altogether.

Take the words of Beatriz Hatz, who just took home bronze in the women’s long jump T64 final in Paris, ““Let’s show the world that people with disabilities aren’t trying to be athletes. No. Let’s show the world we are athletes. We’re elite athletes,” she said “We’re not disabled athletes, we’re athletes. Period.”

This sentiment resonates when considering the ongoing debate about whether Paralympians are Olympians. Technically, they’re not—the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) is a separate governing body from the International Olympic Committee (IOC). The word “Paralympic” comes from the Greek “para,” meaning “beside” or “alongside,” which implies that the Paralympics are parallel to the Olympics, not part of them. There are differences in symbols, dates, competitive sports, and the number of events and participants. But this separation shouldn’t imply inferiority. If anything, it highlights the unique challenges and disciplines of Paralympic sport, and that’s something worth celebrating in its own right. As Howe and Silva (2016) argue, “The unique classification systems in the Paralympics are designed not to segregate but to ensure fair competition among athletes with different types of impairments, showcasing a wide range of physical capabilities”.

celebration

In a recent interview, world record-holding British wheelchair racer, Hannah Cockroft, emphasised the need to “stop comparing the two events as if one is superior to the other”. Instead, she argued, it’s time to appreciate the Paralympics for what it truly represents, a celebration of athleticism that stands on its own merits, without the need for comparison. Jonnie Peacock’s recent comments further illustrate the need for increased visibility. After finishing fifth in the men’s T64 100m final in Paris, Peacock called upon World Athletics president Lord Coe to make para-athletics more “visible” by including his event in future Diamond League meets. “This is a race that I think people want to see,” Peacock stated. “We need to be visible. Paralympics, we need to stop letting it die”. His plea underscores the ongoing struggle for equal representation and recognition in mainstream athletics.

But even within the Paralympics, there’s a hierarchy of disability that’s hard to ignore. Some athletes have less stigmatised disabilities, and this can skew public perception. As highlighted by Fiscella and Bogart (2021), “The Paralympics might only represent those with the most ‘acceptable’ disabilities, leaving others feeling unrepresented. This creates a narrow view of what disability looks like and who is worthy of being celebrated.”

And then there’s the way the media often frames these athletes as inspirational—something that many disabled athletes, like U.S. 17 times Paralympic champion swimmer Jessica Long, find distasteful. It’s not that they don’t want to be role models; it’s that the word “inspirational” often comes with a side of condescension, as if people with disabilities are only remarkable because they manage to do things that non-disabled people take for granted. Jessica Long spoke about her discomfort with this label in a 2016 interview with Ben Shpigel of The New York Times “It’s not a word we like to hear. I’m just doing what I do. I’ve been a bilateral amputee since birth, and I don’t know anything else. I’m not just going to stay in my house and hide.” Sports are sports, athletes are athletes. We tend to celebrate and cherish the sporting moments which move us most, such as the athlete defying the odds to obtain success – something the Paralympics is nothing short of. It upholds that we celebrate these athlete’s for their remarkable achievements, not because of their achievements relative to the disabilities.

As I sat on my sofa with the TV on full blast, scrolling through my phone, and nodding at my boyfriend as he told me about football, I stumbled upon a controversial aspect of Paralympic media coverage—the official TikTok account for the Paralympics. Recently, the account faced backlash for allegedly mocking disabled athletes.

A notable incident involved a clip featuring Brad Snyder, the visually impaired triathlete who lost his eyesight in an IED explosion while serving in the US Navy, during the 2021 Tokyo Paralympics. As Snyder approached the cycling leg of the paratriathlon, he couldn’t find his helmet. Using his hands to feel around him, he appeared to be playing an imaginary piano until a guide directed him to the helmet on his bike seat. Snyder eventually strapped it on and went on to win a gold medal. The footage, cut into an 11-second clip, was paired with a piece of Beethoven music, as though Snyder were playing the piano to the tune, with the caption reading, “Brad Snyder on piano while on his way to winning gold with guide Greg Billington. He loves a bit of Beethoven.” This video has been viewed more than 37 million times and pinned to the top of the IPC’s TikTok account, which has rapidly grown to 4.7 million followers, 176 million ‘likes’ and nearly 2 billion video views. Comments under the video ranged from, “My jaw already dropped but SEEING THAT THIS IS FROM THE VERIFIED PARALYMPICS ACCOUNT MADE ME GASP,” to “This is bad” and “WTF do these athletes think of this?!”

Snyder himself was not offended by the video. He spoke to the Washington Post, saying, “There are some who feel the way that they’re utilising humour is somewhat disrespectful to those who are navigating the challenges of being disabled in a variety of different ways. I do not have that perspective. I think that the account is brilliant in a variety of ways, and the proof is sort of in the pudding. … Thirty, 40, 50, 60 million people are taking a look at the Paralympics specifically and now are interested in engaging with something that has really struggled to find a major footing around the world.”

In a similar vein, Richard Glennie also shares, “I think it’s great for awareness and getting more eyes on para athletes—we were talking about the games ahead of time—unlike most years! The humour is coming from the right place, it’s thought-through, and it’s backed up by reason. The team behind it have disabilities themselves, which legitimises the humour and means they are able to rebut any criticism. Brave work gets lost, bold work rises”.

Australian Para swimmer, Isabella Vincent, acknowledges some people—whether para athletes or not— find the content offensive, yet she fully supports the International Paralympic Committee’s approach. “The IPC is partnering with TikTok to use the platform to stream exclusive games content, meaning the public will be able to interact with Paralympic content like never before. As for the various videos that have gone viral… most of the criticism I’ve seen has come from people who aren’t Paralympians or haven’t experienced disability firsthand! I find it helpful in normalising the conversation around disability. It’s also important that when people discuss this page, they seek out perspectives from disabled people and Paralympians, especially those who have been featured”, she shares.

But let’s be honest for a moment. The media’s portrayal of Paralympians isn’t just a problem; it’s a symptom of a much larger issue—the way society at large views disability. We’re so conditioned to see disability as something to be pitied or overcome that we struggle to appreciate the achievements of Paralympians as pure athletic prowess. We’re too busy being amazed that they can do anything at all, rather than being amazed by what they actually do.

engaging

This brings me back to that infuriating LimeBike and the young man who left it in the middle of the pavement. He wasn’t just inconsiderate; he was emblematic of a broader societal attitude that overlooks the needs of disabled people until it’s convenient to pay attention. The Paralympics should be a wake-up call—a reminder that disability isn’t something to be pitied or patronised but understood as a part of the human experience that doesn’t diminish one’s abilities.

So where does that leave us? How do able-bodied individuals discuss disability in sport without appearing to tiptoe around the issue or, worse, trying to score social points for being “woke”? Maybe the solution isn’t in finding the perfect words or avoiding every potential misstep. Instead, it might be about shifting our mindset—celebrating people for who they are without unnecessary caveats. And perhaps, it’s about addressing the issues symbolised by those LimeBikes—not just because they obstruct the path, but because they remind us that the world isn’t always designed with everyone in mind. Rather than merely navigating around these obstacles, we should strive to create a more inclusive and accessible environment for all. It’s up to all of us to confront these challenges and ensure our world accommodates everyone’s needs.

I’m keen to hear your thoughts. Do these points resonate with you, or do you see things differently? Maybe you’ve got extra insights or agree with some bits but not others. Share your thoughts with us on @glorioussport – drop us a DM and let’s keep the conversation going!

Title image Motion blur of Lea Bayekula BEL leading the athletes in the Para Athletics Women’s 800m – T54 Final. By OIS/Adrian Dennis

References

Channel 4. (2024). ‘Considering What?’ Campaign for the Paris 2024 Paralympic Games by 4Creative.

Nike, (2024). ‘Winning is Winning.’ Campaign for Paris 2023 Paralympic Games by Nike

Fiscella, N., & Bogart, K. (2021). Hierarchies of disability and representation in the Paralympics. Disability & Society, 36(2), 298-310. / What the Paralympics Can Teach Us About Ableism in Sports (2022)

Garland-Thomson, R. (2002).”The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography.” Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities, 56-75.

Howe, P. D., & Silva, C. F. (2016). The classification systems in the Paralympics: Ensuring fair competition among athletes. Sport in Society, 19(4), 440-450.

Shpigel B. (2016) Paralympic Athletes Least Favourite Word: Inspiration. New York Times (2016)