Style Star: Charlotte Perriand’s Singular Vision

Charlotte Perriand is the trailblazing architect behind the iconic Les Arcs resort in France. We find out why she has yet to become the household name she deserves, despite her work and influence being found everywhere.

By Lucy Shrimpton

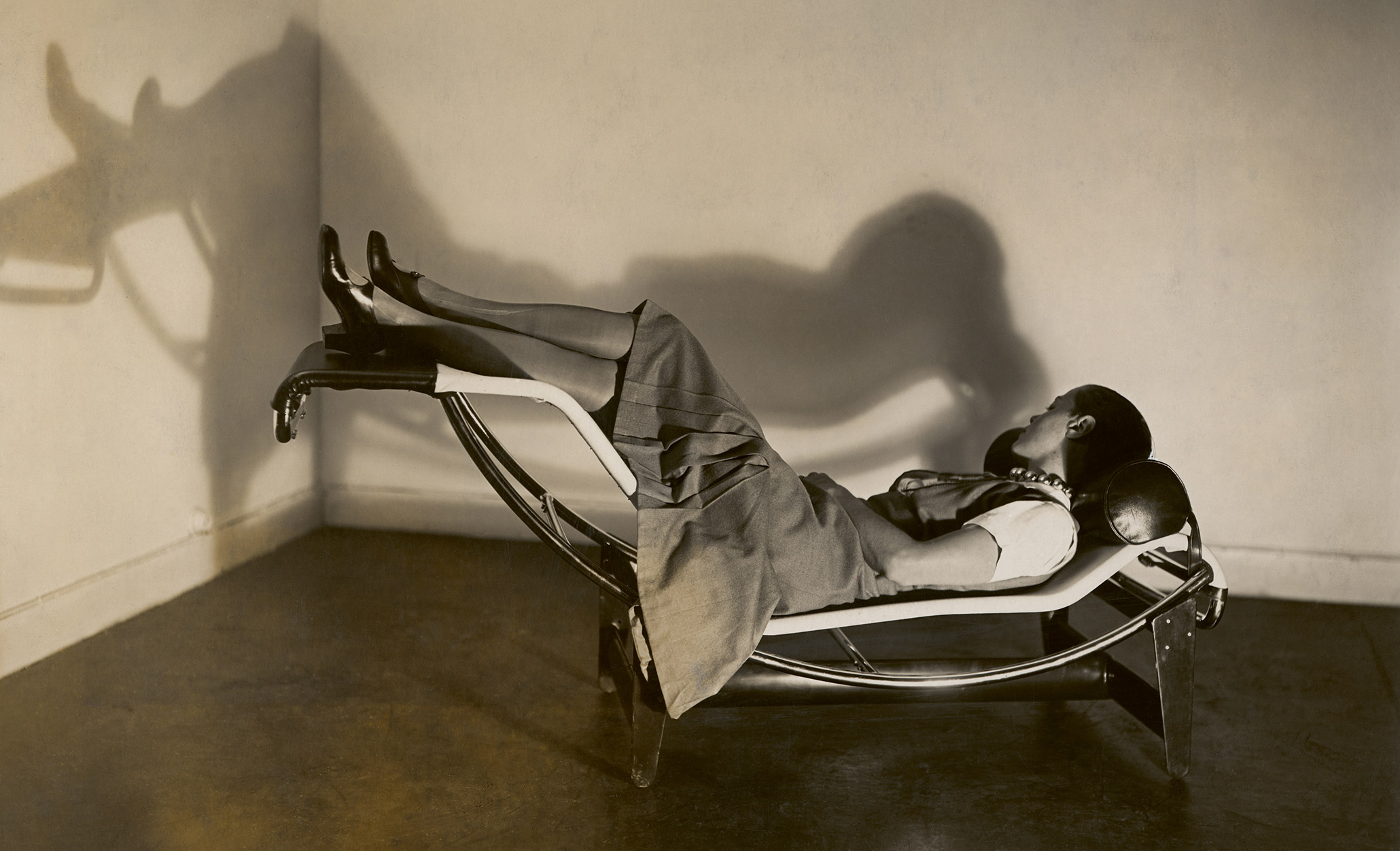

In October 1996, a pair of bright pink Nike trainers walked energetically into the Design Museum in London. The feet in them belonged to Charlotte Perriand, a French designer whose work was being curated there in her very first UK exhibition, and were 93 years old to the day.

From 1968, when she was in her seventh decade, right through to her ninth, Charlotte had been working on a project she’d devoted the last 20 years of her career to: the radical design of the ski resorts known collectively as Les Arcs in the French Alps. But as if being an ‘older’ woman in the then male-dominated discipline of architecture didn’t already mark her out as a French great, it’s what she sought to achieve in the execution of that project that seals her status as a visionary. Decades before the French government appointed Marlène Schiappa its Secretary of State for Gender Equality, decades before the climate chimes of doom sent tourist boards into a whirlwind of eco-initiatives, and decades before a pandemic gently reminded us all that immersion in nature works wonders for mental health, her conviction that design could play an important role in society was the driving force behind her sketches. Way ahead of the 21st century zeitgeist, and very much led by instinct not trends, Charlotte, it seems, had something of a crystal ball.

Imagine for a second that Instagram had been ‘a thing’ back in Charlotte’s day, then scroll down from the pink trainers post. What you’ll detect from the timeline above all else is a series of wintry landscapes showcasing modernist architecture more commonly associated with metropolises. But this is in fact Les Arcs in alpine territory, a cluster of ski resorts each differentiated by a digit denoting its altitude – Arc 1600, Arc 1800 and so on. Most significantly, these constructions weren’t just progressive in the way their facades packed an aesthetic punch, but in the way they were conceived to bring tangible social benefits to everyday French citizens.

CONTOUR

“After World War II,” explains Alison Fisher, Curator of Architecture and Design at the Art Institute of Chicago, “the French government started initiatives to really try to open leisure activities to the masses, and they did this in two areas: seaside leisure on the Mediterranean and winter sports in the French Alps.” Firm believer that the mountains shouldn’t just be the playground of the wealthy elite, Charlotte threw herself into the challenge: to design – in close collaboration with a team of architects, engineers and artisans – mountain accommodation with lower-income families in mind, thus throwing open the pure thrill of alpine recreation to a wider demographic. And the plans for the resort were complex and ambitious, to include “over 28,000 units”. It was imperative to Charlotte that, even with a project on this scale, the mountain should remain the showpiece, not the architecture. And so, in a spirit of innovation, buildings were designed to match the contours of the slopes, so that they’d appear to be cascading down the mountain, without crowding or degrading it.

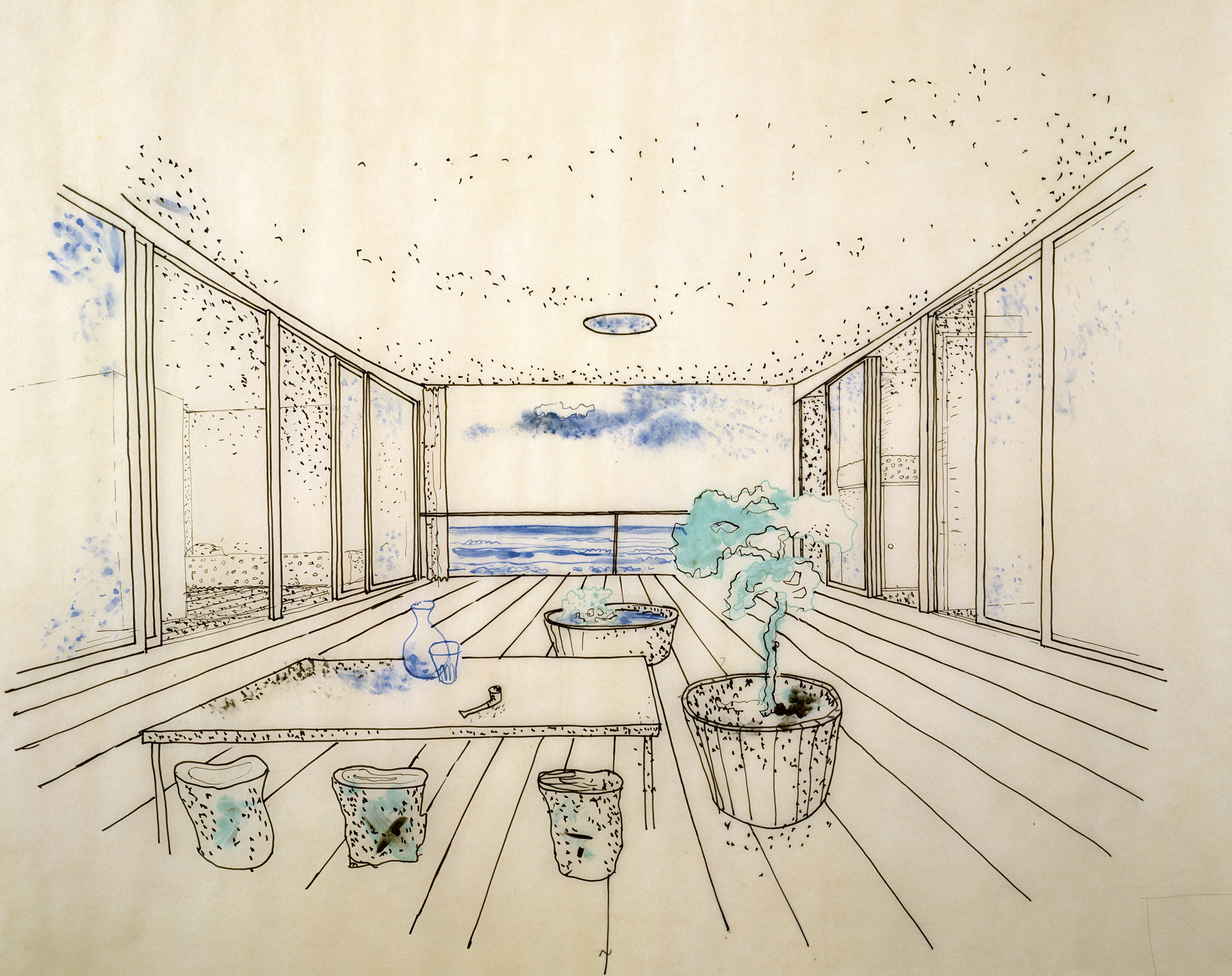

Minimising the visual impact of large-scale constructions wasn’t the only way Charlotte sought an environmentally responsible approach to architecture either. It was also vital to her that the footfall of increased visitor numbers should not negatively impact the countryside and, as such, the decision was made to ban cars from the resorts. Simultaneously, she insisted that ‘mazots’ – existing stone cottages that had been built by mountain shepherds – should be preserved, and where new buildings were to be constructed, traditional elements such as wood cladding, stone and slate should be integrated into them. Charlotte also played a part in establishing the notion of a summer season: a year-round suite of multisports made available not just to make the resorts more viable but also to give visitors the same kind of access to nature that she herself had always enjoyed: she was after all a true “hiker and adventurer,” Alison Fisher adds, “and was extremely comfortable being in the outdoors by herself.”

INNOVATION

As with any architectural project on this scale, it wasn’t all about the exterior aesthetic; the design principles within the walls of Les Arcs’ buildings were of equal importance. Central to Charlotte’s vision was that apartments should be open plan, so that women wouldn’t be locked away cooking while the rest of la famille sat back and enjoyed their holiday on and off piste. Granted, by today’s benchmark, the assumption that women would still be tied up with the domestics may seem like a half victory, yet this was nonetheless groundbreakingly progressive in its day. Apartment owners who put up resistance to her revolutionary layout plans came to recognise that Charlotte was not for turning after she announced she wanted to personally meet each of those who wanted to return to a classic closed-off kitchen. And this conviction that women could throw off the shackles of their housecoats was nothing new to her; “Better to spend the day out in the sun,” she said in a 1950 publication called Art d’Habiter, “than dusting your useless objects.”

Minimalism

For cost effectiveness and thus affordability, apartments were identical, prefabricated, modular and small, whilst windows were huge and balconies raised, giving the illusion of seamlessness with the outside world. Apartments’ minimalism and subdued palettes had a dual function: to focus the eye on the mountain rather than the interior, and moreover to be practical – Charlotte had a lifelong love affair with storage and the sense of calm gifted by empty space. Furniture – the backbone on which she’d gained her reputation – had to be locally made, she stipulated, marrying modernism with rusticity. Almost like a French Barbara Hepworth, sensual engagement with the natural world was core to her art.

GEOMETRIC

Yet Charlotte is all around. Ask the people who live in Les Arcs apartments today, who’ll tell you that the timeless living space is so well organised, so functional and so simple, that it is a pleasure to live there. Ask the kids – now adults – from those lower income families, to whom Charlotte opened up the possibility of experiencing the pistes. Ask Les Arcs tourist office, who half a century later still refer to Charlotte’s legacy when they set out their vision for sustainable mountain tourism. No doubt Charlotte would approve of its latest eco-initiatives: water direct from the mountain source in a bid to eliminate plastic bottles, and return funicular passes supplied to virtuous visitors who’ve opted to arrive at the resort’s Bourg St Maurice by train.

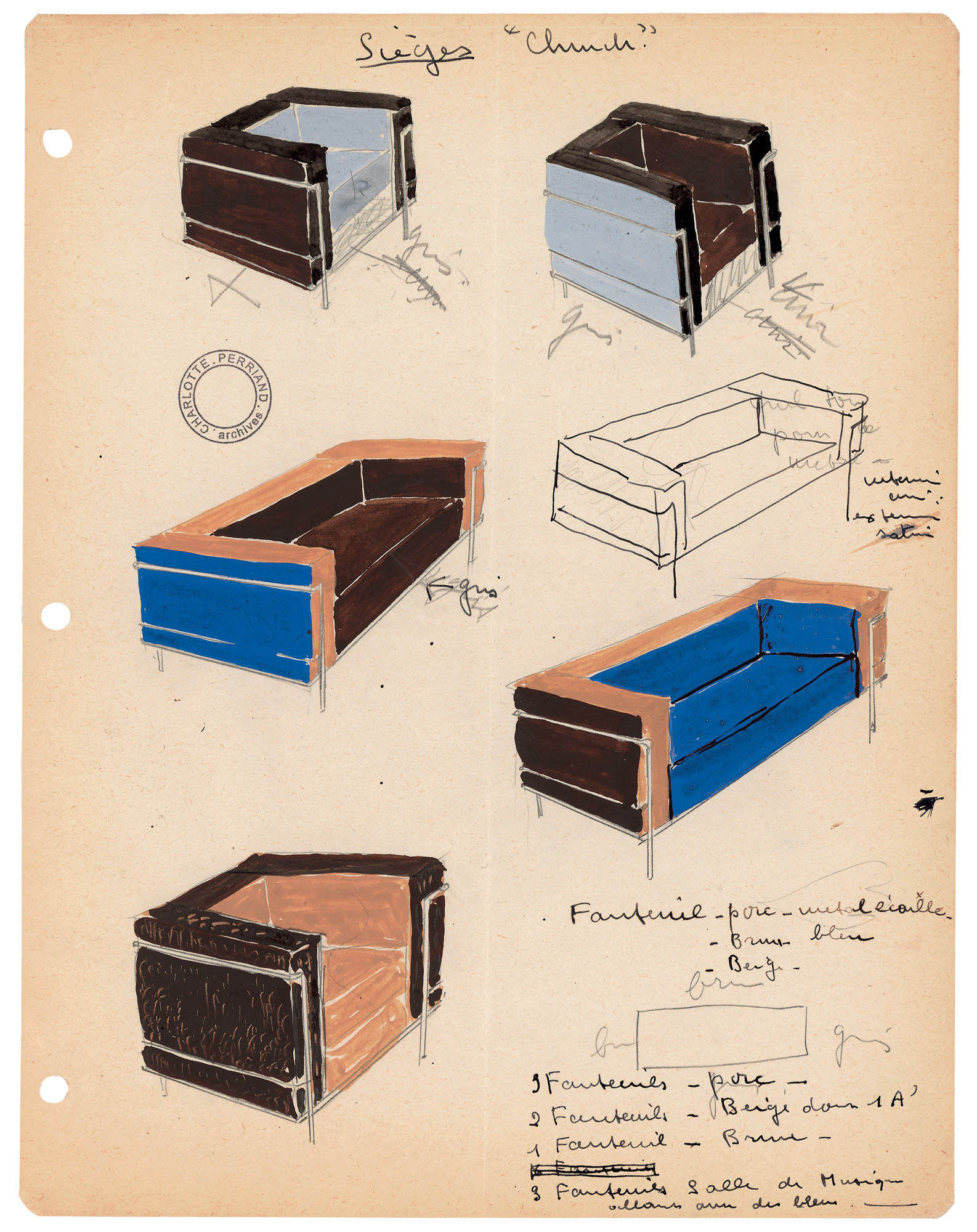

FUNCTIONAL

Scroll down the timeline again and you’ll find the powdery scenes giving way to sketches, prototypes and realisations of her earlier career’s classic furniture – characterised by clean lines, tubular chrome, geometric form and ergonomics. And it was a reputation she’d fought for after tenaciously elbowing her way into the male arena of design and architecture – all pre-1940s when French women were still denied the vote. Early rejections – including one from the utopian architect Le Corbusier who initially dismissed her with a ‘we don’t embroider cushions here’ – became firm and enduring collaborations, yet recognition for her work was frequently attributed to her male counterparts. This was an injustice echoed years later in her autobiography when she recalled the comment: ‘This was done by some old lady who worked with a geezer called Le Tordusier’, overheard by a tourist in Les Arcs. After Charlotte’s death in October 1999, no grandiose monument was ever erected in her name, the only tangible trace of her achievements was a French Ministry of Culture plaque testifying to ‘Remarkable 20th Century Architecture’ and a series of guided architecture tours conducted by the tourist office – on skis.

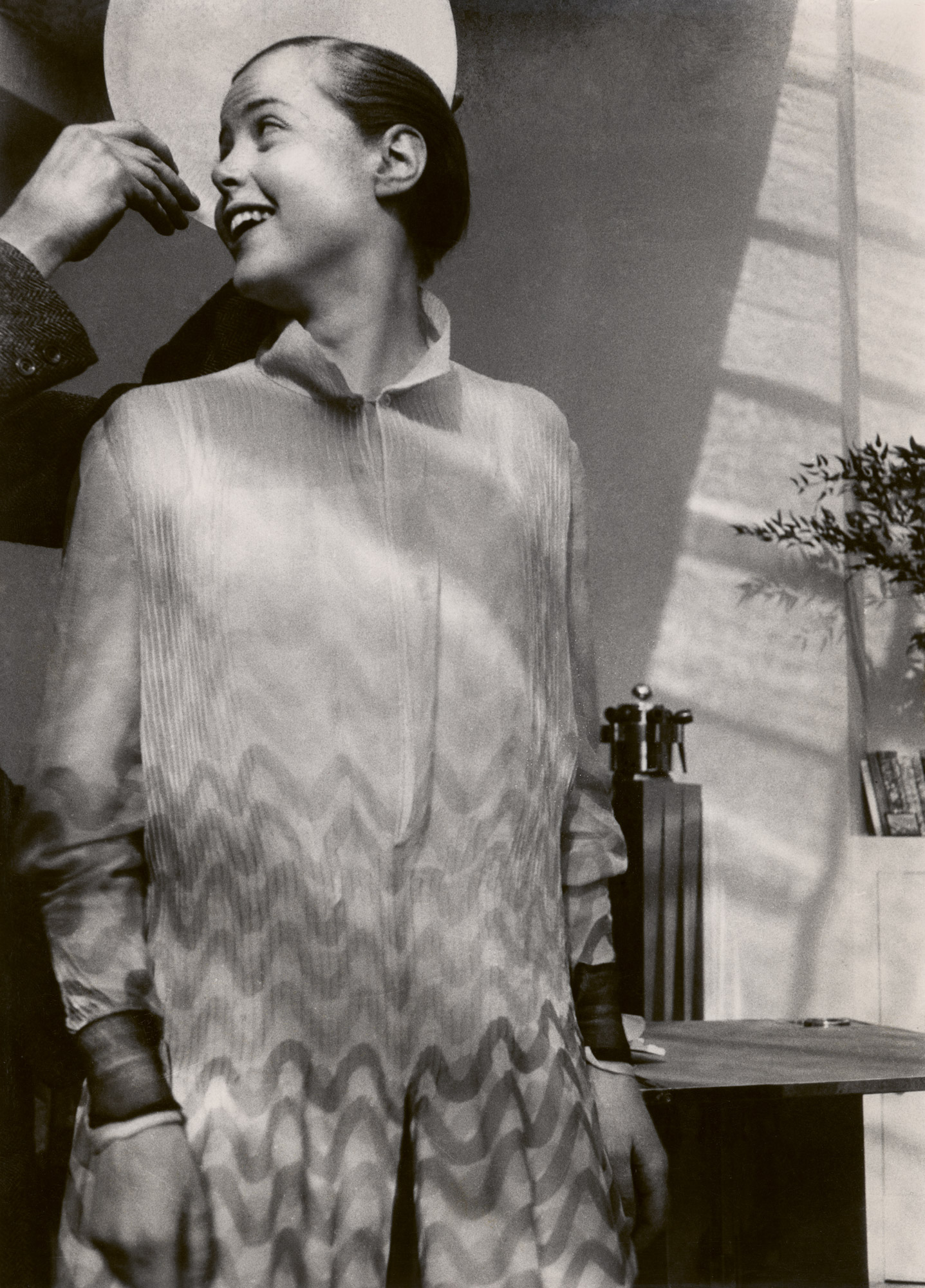

And off piste too, Charlotte – free spirit, bon viveur, luminary – continues to inspire. At London Design Museum’s latest Perriand exhibition – ‘A Modern Life’ [2021] – people noticeably lingered at the blown-up photographic portraits of Charlotte, her unmistakable joie-de-vivre pulsating in black and white. How many of those passers-by were encouraged by the realisation that women can achieve long after the stage of life they’re programmed to think of as their sell-by date “not bound by conventional expectations of what women could do” – in the words of Alison Fisher. Charlotte’s example demonstrates to women that passion, energy and creativity can increase with age, not decline. The ‘… old lady who worked with a geezer called Le Tordusier’ is some tour de force.

Editorial Design Root

Photography supplied by The Design Museum and Les Arcs Tourist Office