Pitch Pandemonium

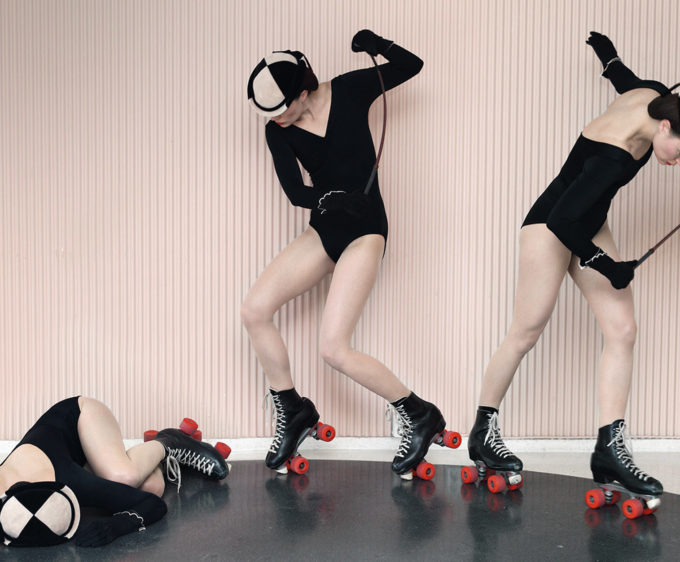

Ducks, dives and Dionysian chaos. American photographer Pelle Cass' composite pictures distil all the excitement of athletic events into single, tumultuous tableaus

By Daisy Woodward

Photography by Pelle Cass

Some one hundred volleyball players leap vigorously around a court, endless balls flying, ponytails caught mid-swing. A group of pole vaulters appear to have leapt at the exact same moment, resulting in a suspended, disarrayed mass of bodies and poles. Dozens of divers hypnotically swoop, loop and plunge into a pool, with dangerous proximity to one another.

At first glance, the images of American photographer Pelle Cass look like sporting events run wild – as if quadruple the usual number of players in any given event have been let onto the pitch at once, with no referee, producing heady patterns of movement.

Look a little closer, however, and you’ll notice that none of the protagonists seem perturbed by their frenetic surroundings, instead remaining entirely focused on their own pursuits. This is because Pelle is far from your average sports photographer. His images are in fact composite pictures, made by taking up to a thousand photographs during the course of a single sports match and using Photoshop to create one work – or what he termed “a kind of a still time-lapse” – from these thereafter.

“I got into composites with my earlier series of street photographs,” the Massachusetts born image maker told me over Zoom from his home in Boston. “I was looking right out of this window,” he said, gesturing to a tall window to the right of his desk. “And wondering what had happened on this street in the past. In my mind it turned black with activity: cars, people, birds, dogs, presumably smoke, fires… And then I realised I could capture some of that [activity] myself with a camera, just by waiting.”

Pelle, who is now in his mid-60s, has always been an avid sports player, but it was only when a magazine approached him to shoot a basketball game in 2015 that he decided to turn his lens to athletic occasions. “And of course the set-up, with everything happening in a contained space, was perfect for making composites. But I can’t even claim pure credit for my own idea,” he chuckled.

MOVEMENT

It wasn’t until two years later, however, after being made redundant, that Pelle started making his ongoing acclaimed series, ‘Crowded Fields,’ capturing student athletes in all their energetic glory. “I was sitting there with tons of time suddenly wondering what to do. Then it occurred to me that you can walk into almost any college sports stadium in the United States and take pictures – as very few of them require a permit. So I started checking calendars, seeing when somebody was playing something, and going along with my camera and tripod. And that’s when it took off.”

THEATRICALITY

What is evident throughout Crowded Fields – which spans everything from hockey, lacrosse, tennis, track and field to swimming, basketball, kayaking and beyond – is Pelle’s inherent understanding of all that competitive sport entails: skill and chance, losses and wins, camaraderie and ruthless resolve. And his rarefied method of documenting the events allows all of these components and juxtapositions to be conveyed within a single frame – a powerful memento of a game’s multiplicitous twists and turns. “I don’t like to watch sports as much as I like to play them,” he explained. “So I think my pictures reflect, for me, the way it feels to play a sport. You’re wrapped up in this turbulent game where the other side’s trying to force you out of control, while you’re trying to maintain it. My pictures fracture the action of sports into little bits, which hopefully creates a nice narrative.”

While there is certainly an air of theatricality intrinsic to Pelle’s images, there is also “an aspect of purity or fidelity to the real world,” as he put it. This is owing to the fact that the photographer always leaves each element of the final work in the exact same place it featured in the initial source image; in other words, “It all happened precisely as you see it, just not at the same time.”

And of course, he notes gleefully, it’s up to him what stays and what goes – “the more mess I can bring in, the better! Birds. Helicopters. Dropped bats!” These are things he scours for among the original photographs, his eye attuned to the smallest of details. It’s no wonder the composition process for one image can take around 40 hours to complete. “I know when I’m finished because it starts looking worse and worse,” Pelle said when queried. “So I stop and then maybe go back a few steps!”

It has always been important to Pelle to strike a balance between capturing male and female sporting events, although not because he has noted “anything particularly interesting” in the differences between male and female athletes. “It’s more about the sports themselves,” he said. “The ones I like to shoot are the more unusual ones. Watching a men’s shot put competition on a Tuesday afternoon is interesting to me. So is watching women’s field hockey on a Thursday evening. It’s the different techniques I look for – how you hold a lacrosse stick, how the games work – whether it’s men or women playing.”

This fascination with technique and physical form exudes from every work – single out any swimmer, tennis player or baseballer and their stance is always emotive, whether performing a balletic dive, bracing to whack the ball, legs akimbo, or caught mid-sprint. “Often I’m looking for a perfect pose within the context of whatever sport it is – that’s my one sports photographer match-up,” he expanded, “I don’t photograph bad athletes because the more athletic the person is, the more extreme their motion is. And I’m looking for the most expressive or energetic figures, a bit like a figure painter.”

TECHNIQUE

Indeed – as Pelle reveals later in our discussion – the gestural paintings of Italian Rococo artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo and the intricately detailed, vastly populated works of the Dutch painters Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Hieronymus Bosch have all influenced his practice, alongside seminal documentary photographers Gary Winogrand, Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander.

Amid our discussion of the many athletes that fill Pelle’s images, and the “Dionysian chaos” he loves to convey, the subject turned to the pandemic – if Pelle’s pictures were anxiety inducing in their conjuring of claustrophobic pitch based pandemonium before the arrival of Covid19, they were enough to set even the most aloof of hearts pounding. Did this affect viewers’ responses to his pictures? “Definitely. When there’s a pandemic, you see things differently – especially big groups. So people commented on this a lot. Sometimes they expressed feeling frightened, sometimes hopeful, because there are bodies smashed together again; people being close.”

As was the case for many creatives, the pandemic forced Pelle to change tack when it came to the work he produces and how he made it. He actually made some Covid inclined adjustments to some of his previous works, including a basketball court with all players but two removed, socially distanced observers, and hundreds of balls lingering frozen in the air (“it reminds me of that suspended feeling at the start – the sheer sense of surprise that the world could just stop,” he said).

Other projects include “a GQ and Nike collaboration with a world-champion fencer” and a fashion shoot during the pandemic, “which happened in the streets of Vancouver while I was in Boston,” and went surprisingly well. “At first it felt like an essay in terror but I told them what to do: ideas on what sort of locations to use, and how to set up and take the pictures and it was really fun! I would like to do that with one of my regular sports pictures one day,” Pelle enthuses.

EYE-POPPING

A perusal of the photographer’s eye-popping images distils all the excitement of a game into a thrilling tableau of athletic exploits. A limited edition book is available from Just an Idea Books and Pelle’s work will also feature at New England’s deCordova Museum’s ‘New Formations’ exhibition from 7 October 22-22 March 2023.

Photography by Pelle Cass, Editorial Design by Root