Meet The First

Moon boots, elitist skiers and men-only contests. Tina Basich revolutionised snowboarding by breaking the mould so others could follow in her footsteps

By Sam Haddad

As part of the historic first generation, Tina Basich led the charge for women’s snowboarding from the sport’s renegade origins in the mid 1980s to its inclusion in the Winter Olympics in 1998. One of the first ever women to be sponsored, she rode in contests, jumped off cliffs, and starred in magazines and films. She even started her own women’s outerwear brand as she was sick of wearing men’s clothes that didn’t fit. Every woman who snowboards today owes it all to this mould breaker, and in March 2023 Tina will be inducted into the Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame.

In 1985, you didn’t see snowboarders on the slopes. This was across the world, not just at Soda Springs, the small California resort where Tina Basich and her younger brother Mike first strapped on their boards and began to carve their first turns. Resorts were just skiers, and more skiers, as far as the eye could see.

Back then skiing had a reputation as a snooty, elitist sport. It really wasn’t a scene that the Basich children were drawn to, even though they grew up in Sacramento, just a couple of hours from Lake Tahoe (which boasts some of the best ski resorts in North America). “We weren’t a ski family,” said Tina,“We were a skateboard crowd.” Growing up, Tina was a sporty, outdoors-loving kid. She enjoyed soccer, softball, building tree forts and racing dirtbikes with her brother. But most of all she loved skateboarding, which she took up when she was aged 10. Some years later, her mum found a snowboard in a local ski hire shop and suggested that Tina and her brother might like to give it a go. She was 16 by then, her brother 13, and wearing moon boots instead of snowboard boots (as that’s all they had), they took to it immediately “Snowboarding is like skateboarding,” she said. “And we found it much easier than falling on concrete. We were hooked right away. Not just because it was a thrill, but also as it was something new and a little bit creative and edgy.” Yet when they tried to visit some of the other ski resorts dotted around Lake Tahoe, they soon realised not everyone was so enthusiastic about their newfound passion. “The resorts had never seen a snowboard before, so when we went to buy a lift ticket, they said no,” explained Tina.

“The resorts didn’t want us there and the skiers didn’t want us there, they were giving us glares. We were just a bunch of wild punk rock skateboarders. I had bright green hair! We were the rebels and we liked it.” Eventually, they did find one resort, which along with Soda Springs, was happy to have them. Donner Ski Ranch was run by a man named Norm Sayler. “He was up for kids having fun,” said Tina. “He looked at our boards and asked, ‘That thing doesn’t come off your feet, right? No, then we’re good.”

The siblings connected with a bunch of other like-minded snowboarders at Donner. This resort would go on to play a pivotal role in the development of the nascent scene, hosting some of the first snowboard contests in the US and nurturing the early careers of many professional snowboarders, including Tina and her brother Mike. But in the beginning, for Tina at least, it was enough that they “had a place to go.” She had no grand future plan involving snowboarding, though it did quickly become clear it was something special and compelling; a sport a lot of people were suddenly upending their lives for. “Everybody just had to get on the hill every day, no matter what,” she said. “It was not uncommon for people to quit their day jobs and go wash dishes at night in restaurants just so they could snowboard all day.”

Tina changed her plans too by going to college in the summer so she could have the winter off to snowboard. She saved up for her season lift pass by babysitting and tutoring art, as she’d always been creative. “I grew up with a paintbrush in my hand,” she said. Indeed, for Tina, part of the appeal of snowboarding and skateboarding was that she could express herself and style was paramount, unlike the more rigid team sports of her childhood.

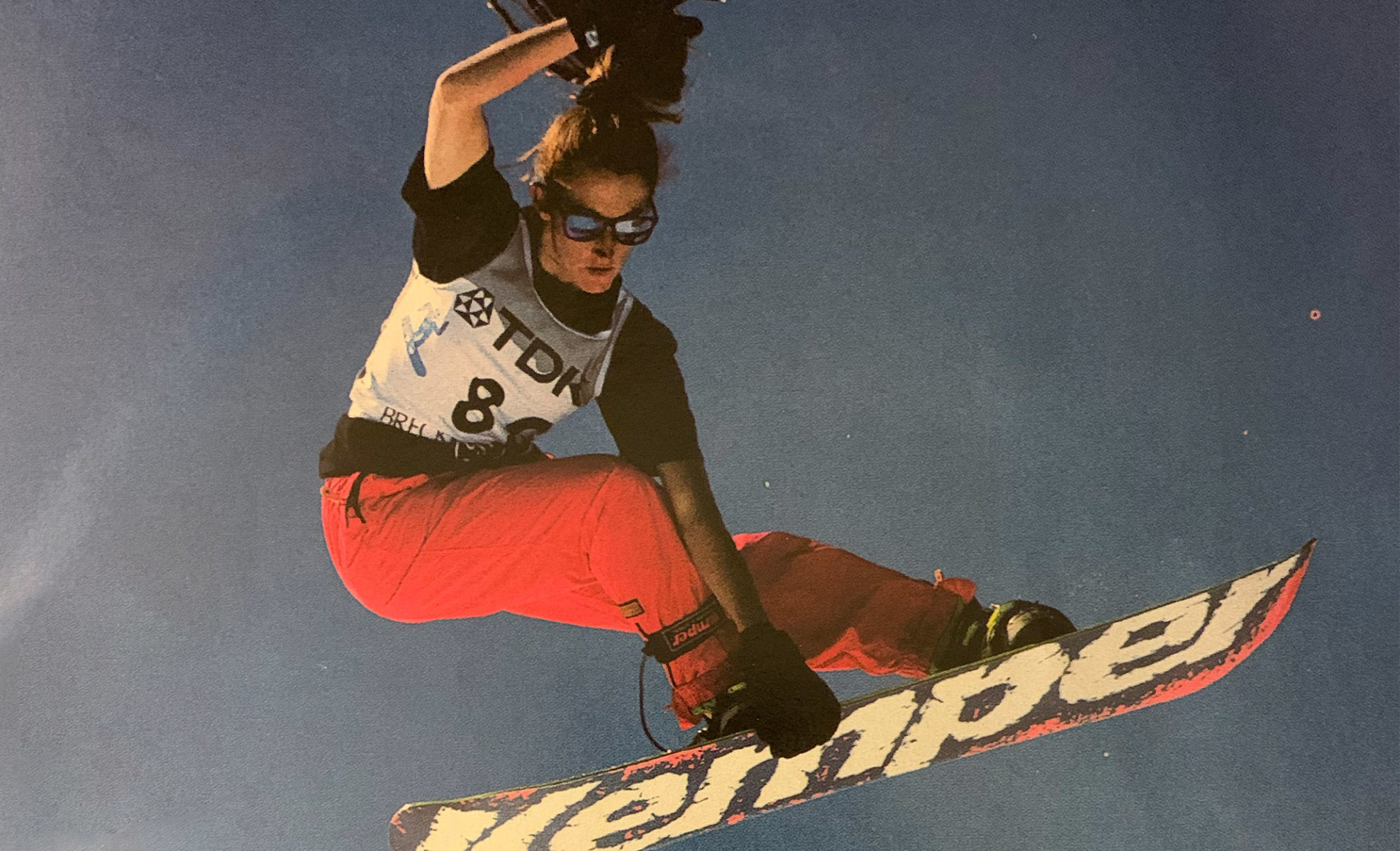

Even though the contest set-up was still quite rudimentary, she started to enter local events, competing in half pipe, where riders are judged on a run of tricks performed on a U-shaped ramp of snow. Tina once added duct tape to her bindings to get better forward lean. Soon she began to compete further afield in Colorado, where, in 1987, she rode in the World Snowboard Championships at Breckenridge. After which she managed to snag her first main sponsor, Kemper Snowboards, who would pay her a modest $250 a year.

It was at the World Champs that Tina realised snowboarding was a far bigger thing than the parochial scene she’d known in California; people had come from all over the world to compete. “Everybody was tripping out on the gear,” she continued, “The Europeans had hard boots, the California crew was all freestyle with people doing tricks no one had seen before. The excitement was totally addictive, and we were not going to let that go, we wanted more.” She also remembers the half pipe as a “little home dug out thing,” a far cry from today’s professionally shaped superpipes, which are constructed by machines and can reach almost seven metres high.

addictive

Things moved pretty fast after that, with Tina’s success mirroring the rapid growth of the sport, which by now was allowed in most resorts. She picked up more sponsors who began to pay for her travel for photoshoots. Tina remembers a memorable winter in Utah in 1990: “The snow was amazing, and all the pros had moved there. We were scouring the mountain and building jumps and shooting photos for magazines. The scene blew up.” Tina also started to become more involved on the creative side of snowboarding, designing her first pro model board with Kemper. “I took on every opportunity,” she says. “Not because I was trying to further my career but because it was just so rewarding.” Snowboarding was still very much a male space back then. It didn’t bother Tina directly; she’d spent much of her life surrounded by boys and was happy in men’s company. But when it came to snowboard kit, it was becoming a problem. “I never felt like an outcast in the scene, but we were drowning in the big men’s clothes,” she explained. “The style at the time was oversized pants and chain wallets and wide snowboards. You couldn’t ride in that stuff.”

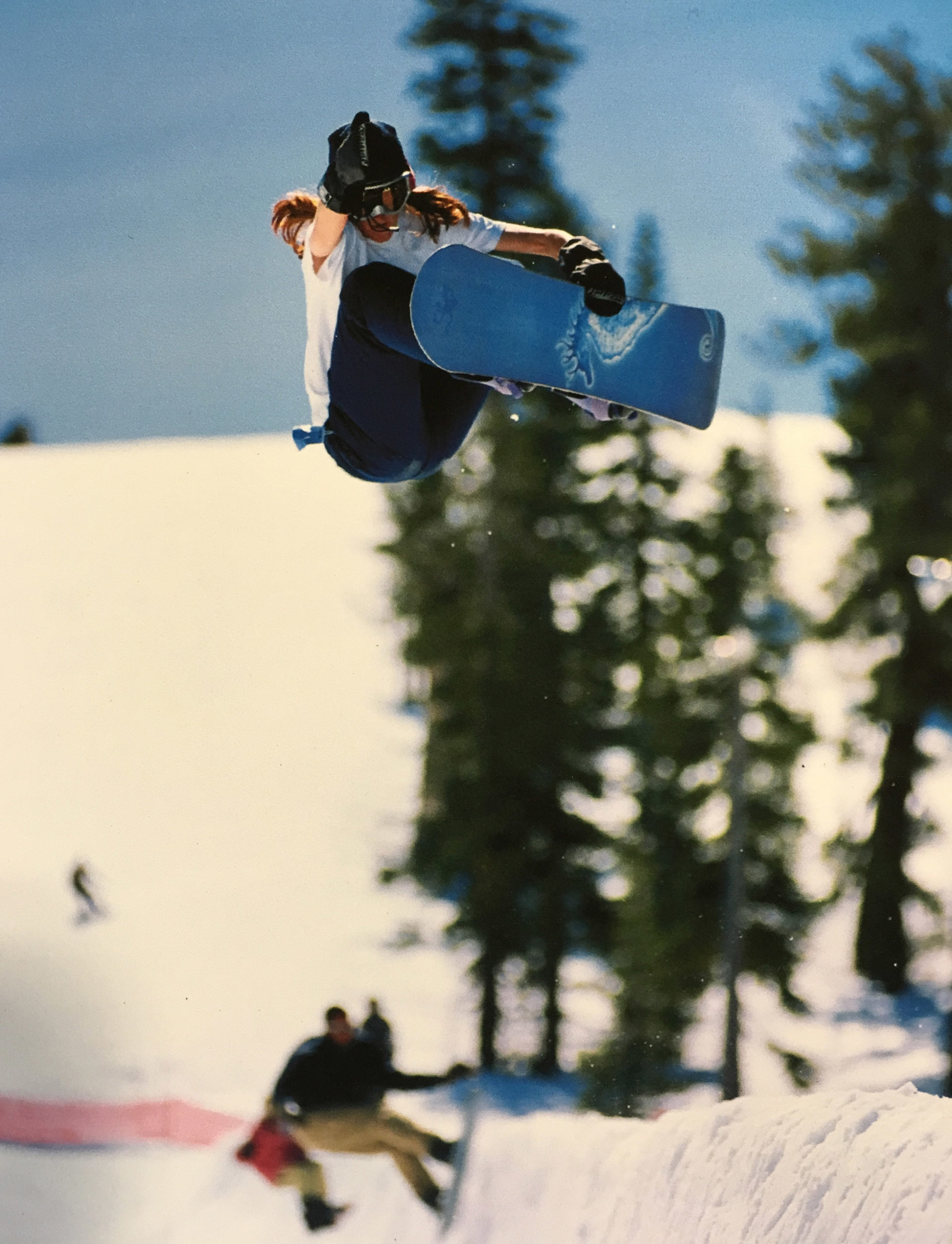

One of her closest snowboard friends was Shannon Dunn, who Tina loved riding with because she raised the standard of women’s snowboarding every time she rode. “She was the first girl to start landing 540s in the half pipe (where a skater and board spin one and a half rotations in midair) so she really upped the level. We clicked personally and we pushed each other, along with Lisa Hudson,” she said. Tina is still close to both women today. Back then the three friends were always sewing up their kit to make it fit, or stitching belts on their pants, so they decided to create their own women’s outerwear brand, another first. They called it Prom Clothing, and made it deliberately feminine, with pastel pink jackets and butterfly logos.

Tina and Shannon also got their own signature pro model boards. Again, a first for women. The boards were made for narrower feet in a lighter weight with more flexibility. “It put some power behind us,” she explained. Tina and Shannon came over to Europe to compete in the Air & Style competition; a historic big air event where riders compete to see who can pull off the best tricks while jumping off a ramp on the snow. But the contest had no women’s division. “They said: ‘No girls allowed,’ but we showed up with our girl boards and pastel pink clothes with hair in ponytails, and we just snuck up the back and dropped in.”

The announcers said: “Those crazy American girls want to jump!” so the women were allowed to jump during the intermission. “It was terrifying,” says Tina, “but those are the moments when you have to push through and be strong and brave. We made our mark.” Tina doesn’t necessarily think the snowboard event organisers at that time were being sexist by not running women’s contests, she thinks it was more a naivete about what women could actually do on a snowboard. “I think it was purely about safety,” she added, “they thought we couldn’t do it, scared we were going to get hurt or weren’t capable, so we really had to show them that we were.”

In big air contests it was commonplace to build a small jump for women and a big jump for men – a debate that still rages today. But Tina and her friends would always hit the big one. “The fact they made a jump for the girls made me want to jump the men’s one more, as that’s how I’m wired,” she laughed. “You think I can’t do that? Watch me!” Tina got a big kick out of confounding people’s expectations around what a girl – or woman – could do. She wanted to close the gap between the genders. “I would come ripping down the hill. At the bottom people would come up to me and say, ‘Woah you’re a girl,’ and it would just make me want to go bigger.”

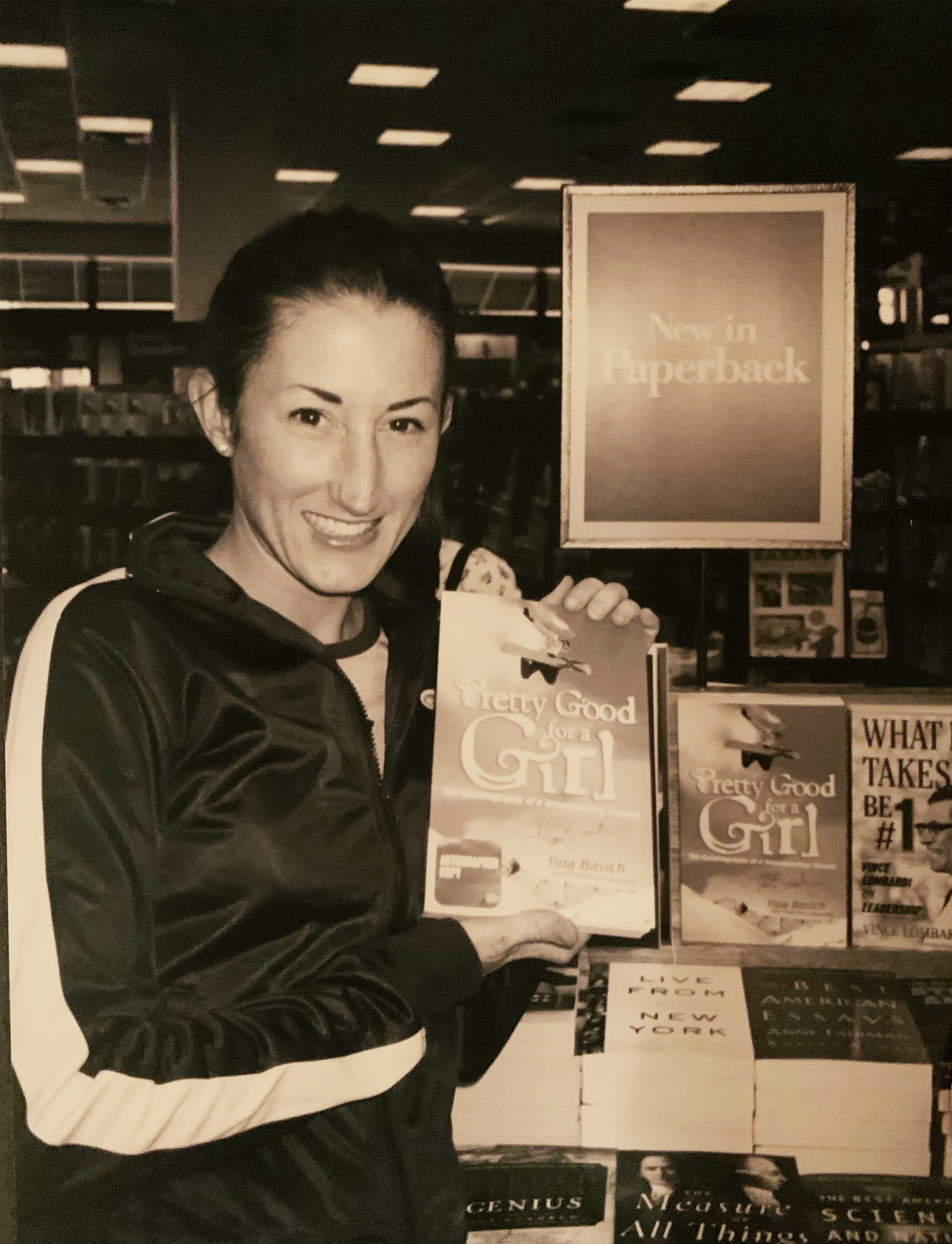

Such moments happened so frequently that when HarperCollins approached Tina in 2003 to write a memoir on her snowboarding life, she knew the title had to be ‘Pretty Good for a Girl.’ Tina cuts a humble figure, but it’s clear that she, Shannon Dunn and others in that first generation of female snowboarders inspired all the women riders who came next.

“Girls would say they started snowboarding because of me. Some would tell me their boyfriend was a snowboarder and after seeing me in a movie they were inspired to do it too.”

“Having those compliments and appreciation that I was not just making my mark, but also inspiring others, was a huge part of my motivation to push forward and not give up,” she said. Tina is also quick to point out that she always felt she had a lot of support from the snowboard community – on the men’s and women’s side – stressing the importance of the male allies who helped her progression. “This included my brother, obviously. It was just like we were continuing our fun childhood together. But this also included other pro snowboarders who helped me learn tricks in the early days, like Andy Hetzel and Dave Dowd.”

Strong & brave

And she benefited from film-makers and photographers backing her, as those relationships would help secure media coverage for her sponsors throughout her career. Tina believes that as snowboarders were already seen as outsiders by the skiing community and beyond, it helped forge a tight-knit relationship across genders within the sport. “There was never any animosity between the riders, we were always cheering each other on. We were the outcasts already, so we had to band together.”

The closeness of the community was really tested when Tina’s great friend and riding partner Monica Steward died from breast cancer at just 28 years-old. Tina and Lisa Hudson set up Boarding for Breast Cancer (B4BC) to honour their friend and educate the younger generation on the dangers of breast cancer and the importance of keeping active. The charity has generated over one million dollars for the cause and continues its crucial work today.

As snowboarding’s popularity grew, so did interest from mainstream media and big name sponsors, which amused Tina and her friends. “We couldn’t figure out why our contest went from having skate shop banners along the side of the pipe to Taco Bell or AT&T. We thought nobody liked us, then suddenly the X Games was broadcast to 110 million people,” said Tina. This meant she got to stay in better hotels and was flown to snowy locations for film or photo shoots.

When snowboarding was introduced to the Winter Olympics in 1998, a lot of riders found that hard to reconcile, and many boycotted the games. “We’re snowboarders, we don’t wear a uniform” was a common refrain, according to Tina. She describes the transition as “interesting,” and she did try out for the Winter Games in half pipe. But by then her focus was on big air, which was only added to the Winter Olympic programme in 2018.

Snowboarding’s inclusion in the Winter Olympics ushered in a new era of professionalisation in the sport, where many would argue technical trick performance and gymnastic ability supplanted style as the primary focus in contests. Social media has also changed the nature of professional snowboarding beyond recognition, and Tina is glad she came up in the sport when she did. “Back then we would do a photoshoot or film in winter but we wouldn’t know if we got anything in a magazine or movie until the following year!” she explained, whereas now everything is instant. A rider goes off a jump and watches the footage right away. The anticipation is gone.

“It’s not good or bad, it just evolves,” she said, “but I would not trade the chapter I had for anything, not even an Olympic medal. The newness and the rawness; being a part of the revolution of snowboarding was priceless to me.”

As a parent now, when she looks back at the crazy stuff she’s done in her snowboard career, she often thinks of her own parents and what she put them through. “I would call from Alaska and say, ‘Oh I got avalanched today but I got out the way, it’s all good. We’re going to a different area tomorrow, it’s going to be a killer. Bye!’ Safety didn’t really cross my mind. But they were always so supportive.” Tina doesn’t do a lot of snowboarding these days. Her daughter Addison has scoliosis, a rare spinal condition, which restricts her ability to snowboard or ski. She’s focused on family life right now, and making art and giftware as her main creative outlet (much of which she sells online). But when she does snowboard with friends, she appreciates it more than ever. “You do as time goes on,” she said.

“It’s funny because a part of me wants to go ripping around and just jump off a cliff or hit the jumps, but I have to be careful and remind myself that I’m not 20 years-old anymore! I still go flying down the hill though, and that thrill is like nothing else, even now.”

To view Tina Basich’s art and giftware, visit Scoliosis Warrior Art and Glitter Girl Studio.