Barrier Breaker

Women didn’t run marathons in the 1960s, but fortunately, Kathrine Switzer’s defiant Boston entry changed the course of history

By Rachel Ifans

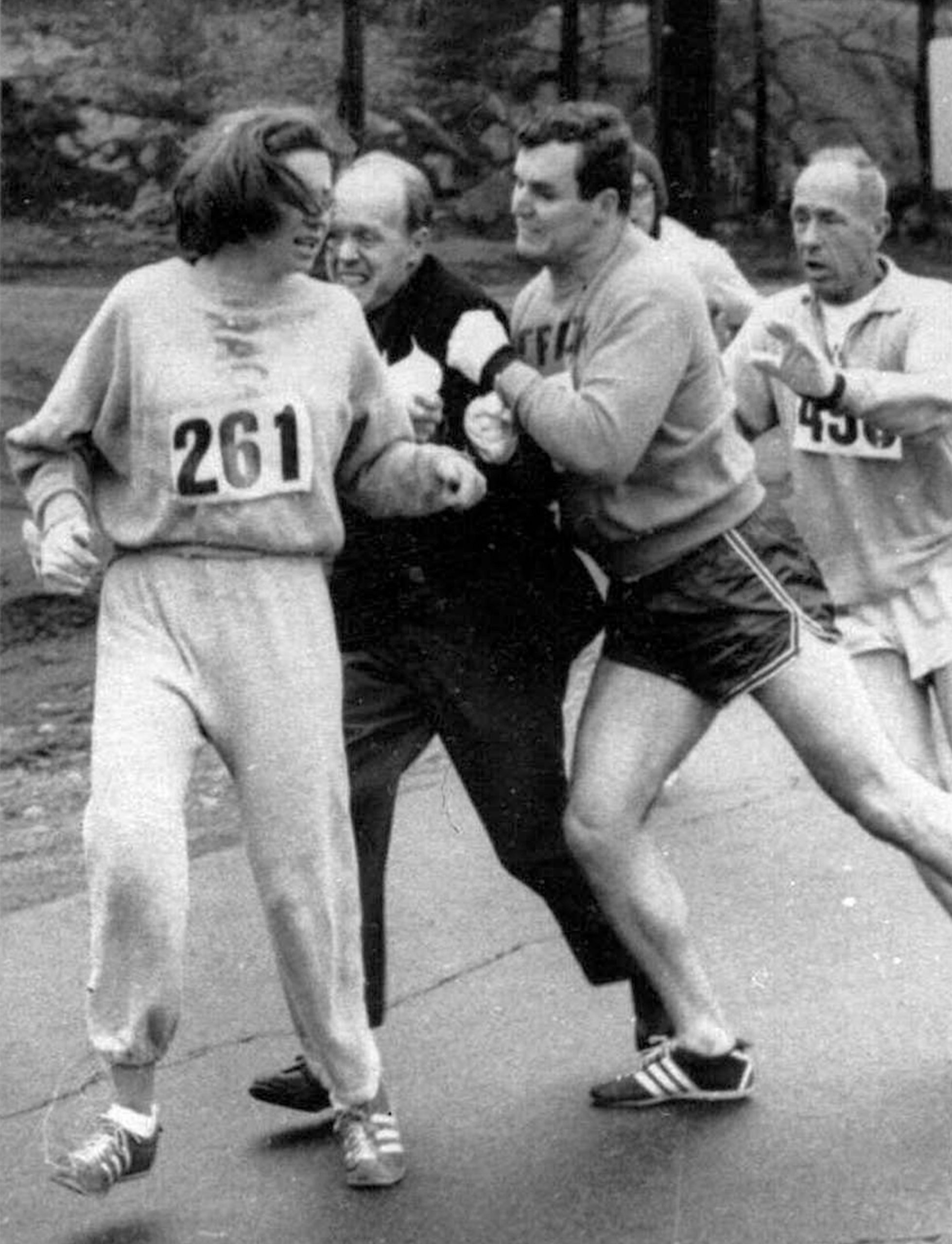

In 1967, Kathrine Switzer became the first woman to officially register and run the Boston Marathon. A photo taken that day became an icon in the history books of women’s rights.

Switzer’s legacy endures, with her groundbreaking 1967 run now marking nearly 60 years since she challenged the norms. Even in 2017, training in New Zealand for the 50th-anniversary Boston Marathon, she continued to inspire generations of women.

It’s a brutally cold day in Boston on April 19th, 1967. A 20-year-old woman stands bundled up in sweatshirts, track pants, and gloves on the start line of the Boston Marathon, hood up protecting her against the snow and biting wind.

Anything can happen in a marathon, and although she’s trained up to 31 miles to leave nothing to chance, nothing can prepare Kathrine Switzer for what’s about to happen, a race that will determine her life path, change the course of women’s sports, and become a milestone in women’s rights history.

History

Back in 1959, Kathrine was 12 years old when running burst into her life. She came home from school one day and told her father that she wanted to be a cheerleader when she went to high school. He replied: “No, you don’t. You want people to cheer for you. Cheerleaders cheer for other people.” The game is on the field, he told her. He said that her high school was introducing something new the following year, called a ‘field hockey team’ and that if she ran a mile a day until then, she’d be the best player on the team. So together they measured out the yard, marked it into laps, and off she went.

“People think the Boston Marathon changed my life, but actually it was all the years in the lead up to that event; the one mile a day I was running as a kid,” said Kathrine, “When I went to high school and was surrounded by big kids, the daily run put a victory under my belt that they did not have. In one class, there was an 18-year-old who was set to graduate and get married the next year, and there I was still playing with dolls. But I wasn’t that intimidated because I was empowered by running.”

Kathrine kept on running. She went to Syracuse University – a powerhouse of sports then and to this day – to study journalism and found there were no sports for women, even though there were 25 on offer for men! She said: “I asked the men’s cross-country coach if I could run on the men’s team and he was flabbergasted. He said no, because it was against the collegiate rules, but he did say I could go and work out with the team if I wanted. “Well, I know he never thought in a million years that I would show up to practice because, when I left his office that day – you know how you hear somebody laugh just before the door closes? – I heard him burst out laughing and say to his colleagues: ‘Well, I guess I got rid of that one.’”

Kathrine remembers how hurt she was at the time, but she showed up to practice nonetheless. She recalled: “The guys were really nice to me so I knew from the beginning that running was somehow different.” There was one guy in particular who wasn’t a runner on the team; Arnie Briggs was about 50, he was the university mailman and ran the Boston Marathon every year. “He was basically a volunteer coach with a clipboard and he felt sorry for me,” said Kathrine. “So, he took me under his wing and he would jog with me every day and tell me stories about the marathon.”

The training miles piled on and one night Kathrine told Arnie that she wanted to run the Boston Marathon. “He said a woman couldn’t possibly run a marathon because women are too weak and too fragile,” she laughed. “I mean we were running 10 miles in a blizzard when he said that but he still maintained I wouldn’t be able to do 26 miles! I asked if he was kidding. I remember saying that my ancestors were pioneers; those women came over to America in 1723, went out homesteading with the wagon trains, had their kids on the way, and busted the sod… I said, c’mon Arnie! But he remained firm; he said: ‘No dame has ever run and no dame ever will.’”

Kathrine explained: “I was so indignant, so I played my trump card. I told him that six women had actually run a marathon already, including the previous year in Boston when a woman jumped out of the bushes and ran the race. I’d seen it in Sports Illustrated.”

Eventually, Arnie agreed that if Kathrine could prove she could run the distance in practice she could enter the race. So they trained the distance – and it was tough. There was one time, at 30K, when Kathrine was so tired she sat down and slept on the side of the road. But she proved her mettle by not only making the 26-mile marker but doing another five miles on top. From then on, Arnie was right behind her. They were filling in the entry form when Kathrine realised there was no mention of gender. “Arnie said, of course not, because nobody in the Boston Athletic Association or the whole world would believe a woman could run a marathon.” They checked the rulebook but there was no mention of women there so she went ahead and signed the form as she always did – K V Switzer – and sent it in.

Kathrine remembers feeling nervous when the bib was handed to her – number 261 in big numbers front and back. “I realised I’d really be noticed wearing that big number. Arnie said, ‘I know and I’m proud of you.’ Isn’t that great? Here’s a 50-year-old guy who’d run the Boston Marathon 15 times – he’d finished in the top 10 a couple of times – and he was putting his reputation on the line for a 20-year-old girl.”

She remembers the whole race as clear as day and the atmosphere being so friendly in the stalls before the start. “All the guys knew I was a woman and they came up to me and said how great it was to have me there. They called ‘way to go!’ and ‘we’re with you all the way!’ as we ran along together.”

But a mile and a half into the race, the atmosphere changed. As the press truck pulled up alongside Kathrine, it slowed down and the journalists on board started yelling at her and teasing Race Director Jock Semple that he had a girl in his race. He lost his temper, leaping off the vehicle and running over to Kathrine. She recalled: “I heard somebody rushing up behind me, so I turned and this fierce guy was right in my face. He grabbed me and he threw me back and told me to get the hell out of his race. He tried to rip my bib off but I jumped back and he missed my chest. I turned to get away from him but he grabbed me by the sweatshirt. Jock knocked him away, then he came back at me and went after the number on my back, catching it and ripping the corner so it was flapping in the wind.”

Kathrine’s boyfriend, who was also running with them, body-blocked Jock so hard he threw him to the side of the road. “Arnie’s eyes got as big as saucers and he screamed ‘Run like hell!’ so we set off running like crazy.”

But Semple was not done. He got up and went to the officials’ office, called the federation, and had Kathrine disqualified from the race and expelled from the athletic federation on multiple grounds: that she’d run more than a mile and a half and that’s all women were allowed to run; that she’d fraudulently entered the race by signing her initials; that she’d run with men; and that she’d run the Boston Marathon without a chaperone.

She remembers the long run and the emotions she went through. “I did get angry at women for a few miles; furious that they weren’t there running with me. And then I realised I was being stupid. I’d had all this reinforcement from parents who motivated me, Arnie who took me under his wing, the guys on the team who were great… Most girls at that time got to age 13 or 14 and were told to no longer climb trees, not to take part in sports, to just look good because their destiny was to get married.” It was this moment when she decided to train hard to become a better athlete and work to create more opportunities for women. And she did. Kathrine, in her own words, “trained her brains out.” In 1975, she ran Boston in 2:51, having won the fight for women to enter officially in 1972 (and won New York Marathon in 1974 with a time of 3:07:29).

She said: “That 1975 time was the third best in the US and sixth best in the world. Wow! I figured if I could go from a 4:22 to 2:51, there were millions of women out there who could run better if they only had opportunities, and that’s when I set my sights on getting the women’s marathon in the Olympic games.”

And the fiery Scotsman, Jock Semple, seemed to grow from the experience too. 1973 – the year after women were first officially recognised in the Boston Marathon – he grabbed Kathrine on the start line and gave her a peck on the cheek for the press photographers. The next day the New York Times ran a piece noting that if Semple was welcoming Kathrine Switzer to the Boston Marathon then times were definitely changing for women. She winked: “I know you’re shaking your head at this, but we actually became best of friends. I’m a very forgiving person and he became a great supporter of women’s running in the decades afterwards. I went to visit him a few hours before he died and as I walked out of the hospital I just knew that his obituary the next day would have the picture of him trying to throw me out of the Boston Marathon.

Since 2017, 261 Fearless has expanded and grown into a global network, continuing to break down barriers for women in running. For all the good things he did afterwards, this one moment of complete misjudgement resulted in one of the biggest social changes in history. It created one of the greatest photographs not only in women’s sports, but in women’s rights; sometimes the worst thing in your life can become the best thing in your life. That picture wasn’t even about running; it was about women’s empowerment and women’s self-belief.

Just as Kathrine was one of the few women to run the marathon distance in the 1960s, she was also one of very few women pounding the streets and parks in training. She says that for the most part people ignored her and Arnie, but she recalled that sometimes they would throw things, shout out of the window, beep their horn or smack their lips at her. She said: “The worst were the women actually; they were the only ones who physically tried to run me off the road with their cars.

FREEDOM

“Arnie would say they were jealous of me. ‘You’re running, she’s not running, you’re powerful, she’s not powerful’. I couldn’t understand why they didn’t just put their trainers on too and Arnie reasoned, ‘You know that, I know that, but they don’t know that yet.’ And he was right. “So many women have contacted me over the years and told me they thought I was the craziest person when they were younger. They say they started running when they were 35, 40 or 50 and it changed their lives.”

In the decades since, Kathrine has worked tirelessly for women’s empowerment in sport, including the growth of her global running network, 261 Fearless, now thriving in 2024.

To satisfy the Olympic committee requirements, she created a global programme of women-only races all around the world in 27 different countries and secured sponsorship from Avon Cosmetics. She was creating change as she ticked off the countries: “I remember Brazil in 1978. I was there organising the first-ever women’s road race and the head of the athletic federation told me that the race was not going to be a success because, he claimed, women in Brazil were feminine and they wouldn’t run.” He predicted that 100 women would take part – 6,500 turned up. Those days it was the biggest women’s road race in the world and there were women taking part who didn’t even have a pair of shoes to run in. “But when somebody gives you a medal and a T-shirt and tells you you’re somebody, you are somebody. And many of those women got in touch afterward to tell me that race had spurred them on to get a job or finish their education.”

The races attracted growing media attention around the world and then in 1981 she met with the IOC in Los Angeles. “Just imagine how nervous I was when they made the decision to open the doors and let me in along with the media. The announcement was made by Madame Monique Berlioux who was the Executive Director of the IOS. I was so happy that she made the announcement because I knew it was significant for her; I couldn’t imagine how tough her job was as a woman leading the male-dominated IOC back then.” So, 1984 was the first Olympics Games to hold a women’s marathon, thanks in large measure to Kathrine.

And now, with the Paris 2024 Olympics just ahead, we can reflect on how the women’s marathon has evolved since 1984, with faster times, bigger participation, and a growing global community that owes much to pioneers like Kathrine Switzer.

Kathrine always kept her Boston 261 bib – with the torn-off corner from the fracas with Semple – and the number has now become a talisman for women’s sport worldwide thanks to the non-profit she set up called 261 Fearless: “The non-profit aims to take women by the hand and say: ‘Come and join us. Just walk with us or run with us, we’re not going to judge you. You’re not too old or too fat or too slow, we don’t care.” Now, in 2024, 261 Fearless is established in 11 countries and five continents – a network of run clubs for women along with an educational programme to empower them to run.

261 Fearless was founded in 2015. In 2017 Kathrine ran the Boston Marathon, 50 years after her first time, with 125 261 Fearless runners. “I couldn’t sleep or eat and I was so nervous. I went to the start line and my legs felt like cooked spaghetti, like I was having a stroke, but as soon as the gun went off, I felt fabulous; it was like the scales were flying off me; all I wanted to do was run.

“I’d always had this amazing fantasy of finishing a marathon and falling into the arms of somebody I love. So I came across the finish line, got my medal, grabbed [my husband] Roger and we had this long kiss and then somebody shouted ‘For heaven’s sakes, get a room!’ It was a moment, it just all came together that day.

“I had been the first woman in Boston wearing a bib 50 years before and now there I was surrounded by 13,500 women. And all along the course people were holding up, waving and wearing 261s and it was really amazing. That was a truly glorious moment.”