In Conversation With Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi

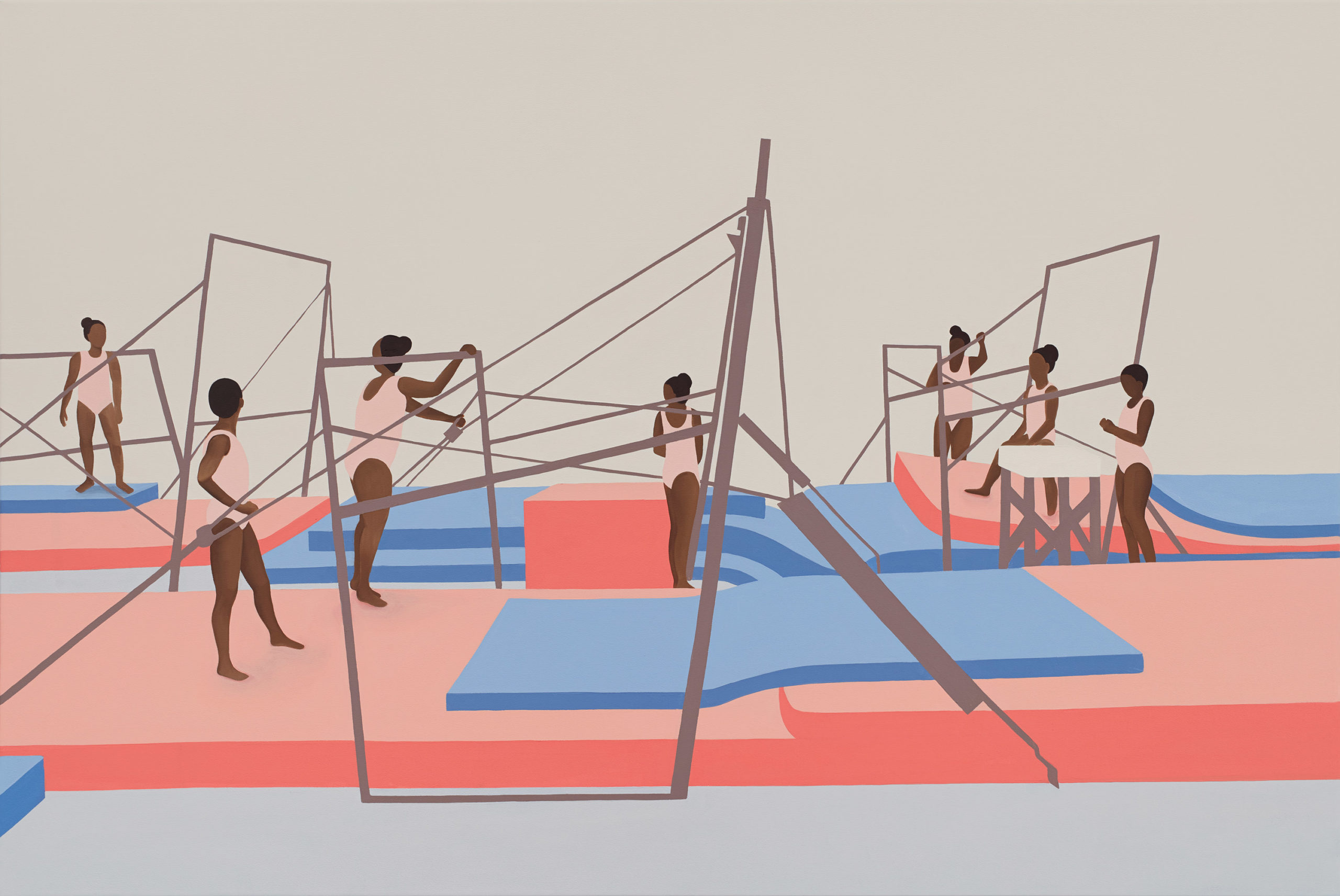

Exploring the performance of identity, this artist’s pastel-hued paintings of young Black gymnasts are manifestations for a future world

By Ashleigh Kane

In 2012, artist Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi was clicking through an online image wormhole when she stumbled on a series of gymnasiums in the 60s and 70s. One image in particular stuck out to her; a white gymnast on the sprung floor with judges and media surrounding them. At the time the image was taken, gymnastics was a predominantly white arena.

In the six decades since that image was taken, Black women in gymnastics have become a force to be reckoned with – Lucy Collins, Dominique Dawes, Gabby Douglas, and Simone Biles are but a few who have made history. However, in terms of numbers, Black women still make up a minority percentage when compared to their white and Asian competitors. Nkosi painted the found image, re-envisioning the gymnast, the judges, and the media as Black characters. It was the first painting of a series which is now known as ‘Gymnasium,’ an artistic journey which is eight-years-and-counting in the making.

While the presence of these great athletes can be felt in the scenes Nkosi paints for ‘Gymnasium,’ her figures are intentionally unidentifiable, with the hope that anyone can see themselves on her canvas. For Nkosi, it’s not about the moments of triumph or lack thereof, but those that happen in-between; two young girls moving mats across the floor, a gymnast awaiting the reaction of the judges, a group huddling around each other in matching pink leotards.

IDENTITY

Initially drawn to the architecture of gymnasiums, the symbolism of the Black gymnast dawned on Nkosi in 2019. After creating two paintings, in 2012 and 2014, she decided to continue the series and found an unexpected affinity with the sport by linking the performance of gymnastics with that of a Black woman’s identity. What might initially pass as everyday scenes that could be taking place at your local gymnasium, Nkosi’s paintings are in fact manifestations of a more equitable world. One where people can share in their own moments of glory or failure, or in everything that happens before, after, or in the midst of those milestones.

Ashleigh Kane (AK): The seeds of this work stem from 2012, can you tell me about this journey? Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi (TNN): I was working on portraits of buildings and portraits of people. I would rarely put a person in an architectural space but I was looking at sports imagery and interested in the architectural and interior space of different stadiums. I landed on this image of a gymnast on the spring floor with judges and the media surrounding them. That was that first painting I did [in 2012]. It was very intuitive for me to make all the characters Black. I altered the judges into something else, either ancestors or witnesses of some otherworldly figure. I have huge image banks. Periodically, I’ll go into them and scrounge around and ask myself ‘What was I thinking when I searched for this thing?’ I found some other images that I’d saved of gymnasiums, and I painted a second image in 2014, which is of the practice room. There’s a bunch of girls in the mirror, and a coach and gymnasts in the corner. Again, I made the characters all Black. In 2019 I was looking for something else to do so I went back and looked at them and then started the project for real; reading, researching, watching a lot of gymnastics, and thinking about what I was actually trying to do.

AK: Did the works become more political as you learned about gymnastics and worked on them over the past decade? TNN: Definitely. Architecture is political as a tool for social control and painting figures is also political for me. The first image that I chose to paint was from the 70s or the 60s. I switched the characters into people who look like me, that are characters of colour in spaces that are typically – or were then – dominated by white athletes. The addition of Black judges and Black gymnasts was a political decision, but it just wasn’t articulated back in 2012. At the end of 2018, when I decided to work on the series, I educated myself about the history of the sport. I also realised there was a personal connection – the metaphor of the world of gymnastics, the field, and the struggles within this field would be powerful. It centered around topics I wanted to talk about; being a woman, a Black woman, having to perform under scrutiny, and, in some ways, perform one’s identity. I didn’t fully understand the power of it – although I understood the potential power was there. I needed to sit down and really parse through it, articulate it, both in words and through the action of painting.

PERFORMANCE

AK: Can you expand on your thoughts on the connection between sports performance and the performance of identity? TNN: On some level, athletes of colour and Black athletes are performing and I think that their identity is inescapable as being part of their performance. It’s something that is thrust upon them. There’s no escaping a reading of your performance outside of your identity. We see that in how people write about Black sportspeople, how they’re reacted to – just think about Serena Williams. She is the perfect example of that. I often think about her in relation to someone like John McEnroe, and the ways in which their behaviour is tolerated or not tolerated; condemned or not; cute or not. That extended to me in my personal experience of being an artist. I’m proud to be a Black woman artist, but can you see my work as work too? Or is it sequestered into this category because of who I am?

AK: When I saw the paintings, first I appreciated their beauty, and then, when I began to learn more about why you did them, I saw them in a totally different light. TNN: I decided that I wanted to be an artist to make things, and put them out into the world for people to think about. I wanted them to react but also feel seen or heard. There’s something affirming about people identifying or being interested in this series. Firstly, it’s because of the aesthetic, and then they’re compelled to look further into it. That’s what I’m trying to do – capture you and hold you. To catch your attention and say, ‘Hey, can we think about this together?’ I’m really moved by the response to this work. It’s the first time I’ve had this visibility. I turned 40 last year and I’ve been working for a long time. I often wondered if anyone was seeing me or hearing me.

AK: The characters don’t have defining facial features, which is different to your previous series ‘Heroes.’ What made you want to leave these characters more vague, or open to interpretation? TNN: One thing I was consciously trying to do in this series was to have the Black girl, young woman, or woman figure act as a stand in for every person. Can this protagonist be anybody? Can you see yourself in this person? They’re a universal person. There’s something similar here to what I was trying to do in the ‘Heroes’ series. I have this belief in the idea that everybody is special, that everybody is a hero, that everybody who I want to remember deserves to be remembered. That all those people make me who I am. I think of that series as a protracted self-portraiture experience. These gymnasts might be at the top of their field or they might not be, but they’re all unique and no one needs to stand out above anyone else. It’s about counteracting some of the individualism that pervades the societies that I live in. Growing up in the US and South Africa, we love celebrity, we love stardom, we love singling out. In South Africa, it’s such a part of our national history – like Nelson Mandela. There were so many people who contributed to the struggle for people and democracy in our country in all sorts of ways. They also need to be talked about and they also need to be memorialised, as do you and I.

UNIVERSAL

AK: Do you have a personal relationship to gymnastics, or to sport more generally? TNN: I don’t have a history with gymnastics, but I studied Wing Chun Kung Fu from my mid-teens into my 20s. It was the single most important discipline for me. It really shaped my interest in the potential and limitations of the human body – how we set those or create them, and how they can be related to our psychology and mental state.

AK: I read that you have described yourself as an artist who is navigating the field of artists social practice. What does that mean? TNN: I come from a family of activists – like people who have actually done real things in their life [laughs]. The big question for me has been: what is your contribution to making this world a more just and equitable place? It’s a reminder to myself that there’s also a world outside of making objects. It’s something that I aspire to – work that is more radical than art.

AK: What do you hope people will see when they see your work, this series? TNN: People feeling seen. I get emails from parents like, ‘Do you have prints of your work? My child is a gymnast.’ The idea of people, and young people, seeing themselves in the work is really beautiful. For me, the idea of Black excellence is important for all of us – that we acknowledge our power, our talent, our hard work, our potential. But I think Black excellence can go hand in hand with Black vulnerability and the need for rest. The need to sometimes not succeed – to fail and learn. I don’t believe in the idea of failure – I don’t subscribe to it. You are in process and progress, so that’s also part of the work; the moments in between where you’ve tripped and fallen. The judges are this weird entity that I’m still figuring out but I’ve painted them as ancestors. The idea of being witnessed but still being adored. I think everybody deserves that.

AK: So these figures are in-between moments of glory or failure, and that’s okay… TNN: Yes. They’re not in the peak moments of success that we usually associate with sport, like, ‘Oh, that person is on their third flip, in mid-air.’ I love thinking about in-between moments, the ones that we would like to hide from public view. The fear of exposure can shut down all potential conversations or lessons. These fear-based ideas of failure are a distraction, they’re obstructive. I’m trying to put my faith in work with my focus on just learning.

Editorial Design Root