Spotlight: Muslim Sportswomen

Why does the hijab tend to grab more headlines in Western media than the success of the woman wearing it? Glorious, with the help of photographer Giulia Frigieri, examines the subject

By Martina Žoldoš

Photography by Giulia Frigieri

A dominant image of a typical female athlete in international publications, social media and even Google search results is of a woman wearing tight-fitting shorts and a T-shirt with visible sculpted muscles and long hair wildly fluttering in the air. Very rarely does a photograph appear of a sportswoman wearing a hijab and a garment covering most parts of her body.

The representation of Muslim sportswomen in international media is often superficial and stereotypical. A hijab worn by a female athlete will often draw more attention rather than her achievements – as if a piece of textile should define performance and identity. Guilia, an Italian photographer, whose work mostly centres on Muslim athletes, agrees that images of sportswomen wearing a hijab are still rare and do have a surprising effect on audiences. “I think that in Western societies people tend to assume that the hijab means repression and constriction. However, that’s not the case.”

As an example, Giulia describes her experience of photographing Amaya, Maysa and Layna, three young Muslim sisters from Hull in England, who spend their free time in a skate park. As the girls, who call themselves Insistergaters, pointed out in an interview for Huck, they never intended to challenge stereotypes that skateboarding is a boy’s sport and that Muslim women are locked in the house, working in the kitchen. They just wanted to do what they liked. “For them, both are empowering tools, they feel better wearing the hijab, they feel better skating,” says Giulia, adding that we shouldn’t centre so much of our attention on the hijab. “These kinds of images are still surprising to some people, but they shouldn’t be. For many women who I have met and do sport, the hijab is not an obligation.”

Another powerful story for which Giulia collaborated with photographs was one about Les Hijabeuses, a collective of young female football players, campaigning against France’s hijab ban. Although the international football organisation FIFA lifted its hijab ban in 2014 and thus recognised it as a professional outfit in official football matches, the French Football Federation still doesn’t allow women professional football players to cover their heads. Hijab-wearing women are therefore asked by the referee to remove it while playing football or leave the pitch and watch the match from the bench.

The women who refused to put down the hijab, but also wanted to continue with their passion for sports, formed Les Hijabeuses. By organising training sessions and connecting with football teams across the country, they encourage other hijab-wearing women to play football and also campaign against Islamophobia in the country in general. As Giulia points out, they’re demonstrating that “playing sport with a hijab is the same as not wearing one, and a hijab shouldn’t create obstacles. They fight for their right to choose whether to wear it or not.” Giulia, who has lived in France for over two years and has now moved to Marseille, is disappointed by France’s attempt to erase every sign of people’s religious difference and diversity. She hopes that the growing media coverage Les Hijabeuses has been receiving will eventually result in France respecting FIFA rules.

represent

Since the beginning of her career as a documentary photographer, Giulia has been focusing her camera on women, especially those from South West Asia and North Africa, also known as the SWANA region. “I think I started this fascination with the Middle East because my first partner when I was a teenager, with whom I was together for a long time, was an Italian Lebanese. At the time, you could only see stories from the Middle East when something bad happened, however I’ve always been intrigued and wanted to know more because what he told me wasn’t what I heard from the media.” Giulia wanted to cut into the flow of negative news by trying to capture positive moments and sharing the stories of everyday life and courage. “I kept asking ‘why is no one telling these stories?’”

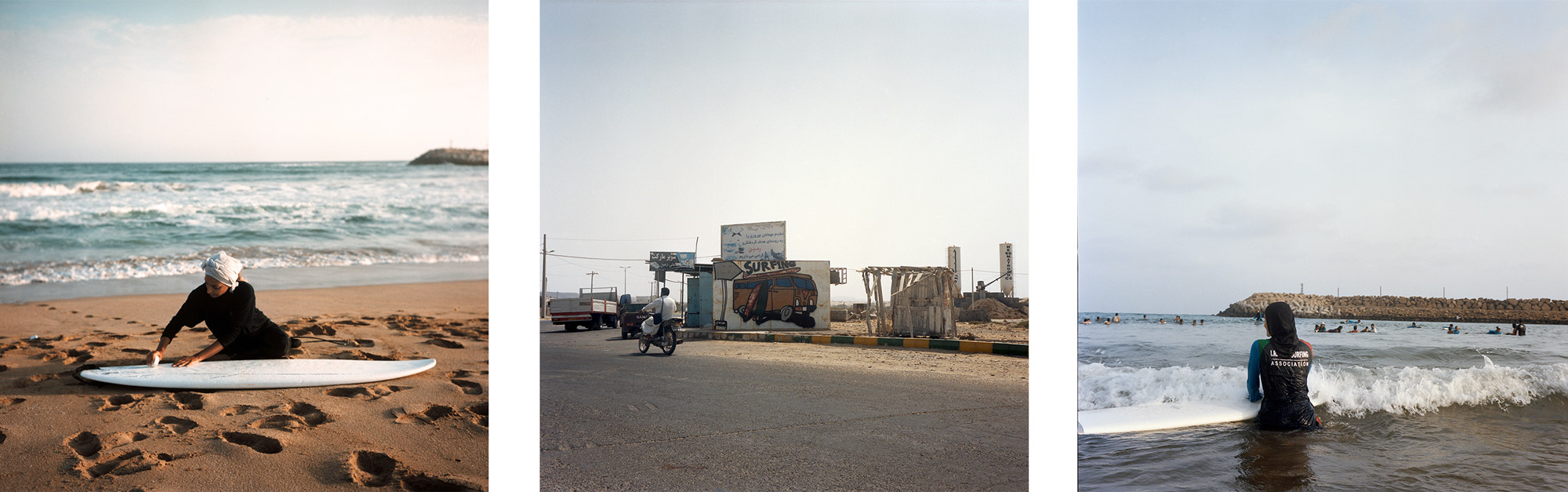

Her attraction to the SWANA region led her to visit Turkey, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman and Iran where she accidentally stumbled upon a story that would make her the winner of a 2019 Portrait of Humanity prize. She says: “When I went to Iran in 2014 for the first time, I met some people who told me about a group of people surfing in the region of Chabahar in southern Iran.” The story really intrigued her; Iran usually doesn’t appear on the maps of the world’s greatest surfing spots. “Until recently no one was surfing in Iran because no one knew it was possible.”

After doing some research, she found information about an Irish professional surfer Easkey Britton, who a few years earlier discovered that the waves along Ramin beach in Iran had potential. With a French filmmaker Marion Poizeau, Easkey filmed an award-winning documentary called Into the Sea and started an Iranian surfing revolution by teaching snowboarder Mona Seraji and diver Shahla Yasini to surf, the first two women in Iran to do so.

With Easkey’s help, Giulia contacted Shahla, one of the protagonists, who pioneered the scene that has been rapidly developing ever since. Between 2017 and 2019, Giulia visited Shahla twice. During the stay, the two young women developed an intimate relationship and the result was a series of photos Giulia titled Surfing Iran. The portraits of a young Iranian woman with a surfboard soon appeared in several major publications. Giulia argues that she never intended to make a statement or cause shock by portraying a Muslim woman. “I just wanted to highlight a positive story from the Middle East, capture a moment of everyday life, of people doing positive things, normal things.” Despite the fact that no other woman had surfed in Iran before, Giulia confirms Iranian women regularly engage in almost all sports disciplines (boxing is, for example, forbidden); at least they did in 2019, before the protests, when she visited the country for the last time.

She says: “It’s true that they had to respect the regime’s rules, such as covering the head, but it was possible and this was something I wanted to picture.”

Giulia, who herself is a passionate sportswoman, dislikes it when communities are excluded from practising sports. “Everybody should be given the opportunity to access sport,” she says. For years, she has been practising yoga and swimming, and more recently aerial dance. “I was also running but I stopped because my body couldn’t take it anymore. I’ve also enjoyed diving and would love to do more.” For Giulia, sports is a healing process, a powerful empowering tool that boosts confidence, makes you feel more comfortable with your body and creates a bond with the people who share the same activity. “When everything is bad around you, sports is the only thing you can return to to find peace in your mind.”

For Giulia it was natural to combine her two passions, sports and photography, which she considers a great bonding tool, especially when the photographer and the portraitist don’t share the same language, as often happens in her case. “I believe photography helps you get closer to people.” Her most faithful companion has been a Rolleiflex camera, a medium format reflex camera with two lenses of identical focal length, where one transmits the image to the film and the other serves as a viewfinder. The latter is mounted on top of the camera, which the photographer holds at the waist and looks into from above. “I love this way of photography because I never point my camera directly into their faces. I don’t like to work with normal cameras anymore because it feels like I’m entering into people’s intimacy too intensely. I do get close to people but I find it a nicer way to start my relationship with my subject.”

When talking about portraying hijab-wearing sportswomen, Giulia touched on the sensationalism of Western media and their reporting about Middle East sportswomen who have put down their hijab to participate in international competitions. The most recent events that went viral were stories about an Iranian boxer and climber. Giulia admits that Iran is a situation of its own, because the hijab is obligatory and many people don’t want to wear it. She absolutely supports both women and their actions, “because it’s a very political statement towards what’s happening in the country” and she hopes the regime will fall. “But I feel that there’s a little bit of glorification of Muslim women in sports or women in general taking off their hijab. There’s a tendency to make a hero of people who decide to become more Western.”

Giulia recognises this tendency as wrong and hopes that “in five or ten years’ time there won’t be any difference between women succeeding in sports wearing a hijab and women succeeding in sports without a hijab.” She also believes the key is to continue publishing more stories depicting hijab-wearing sportswomen as something ordinary.

Photography by Giulia Frigieri, Editorial Design by this is root

Title Image – Shahla & Shams, Ramin Chabahar, 2017. From the series Surfing Iran.