Wheels Of Change

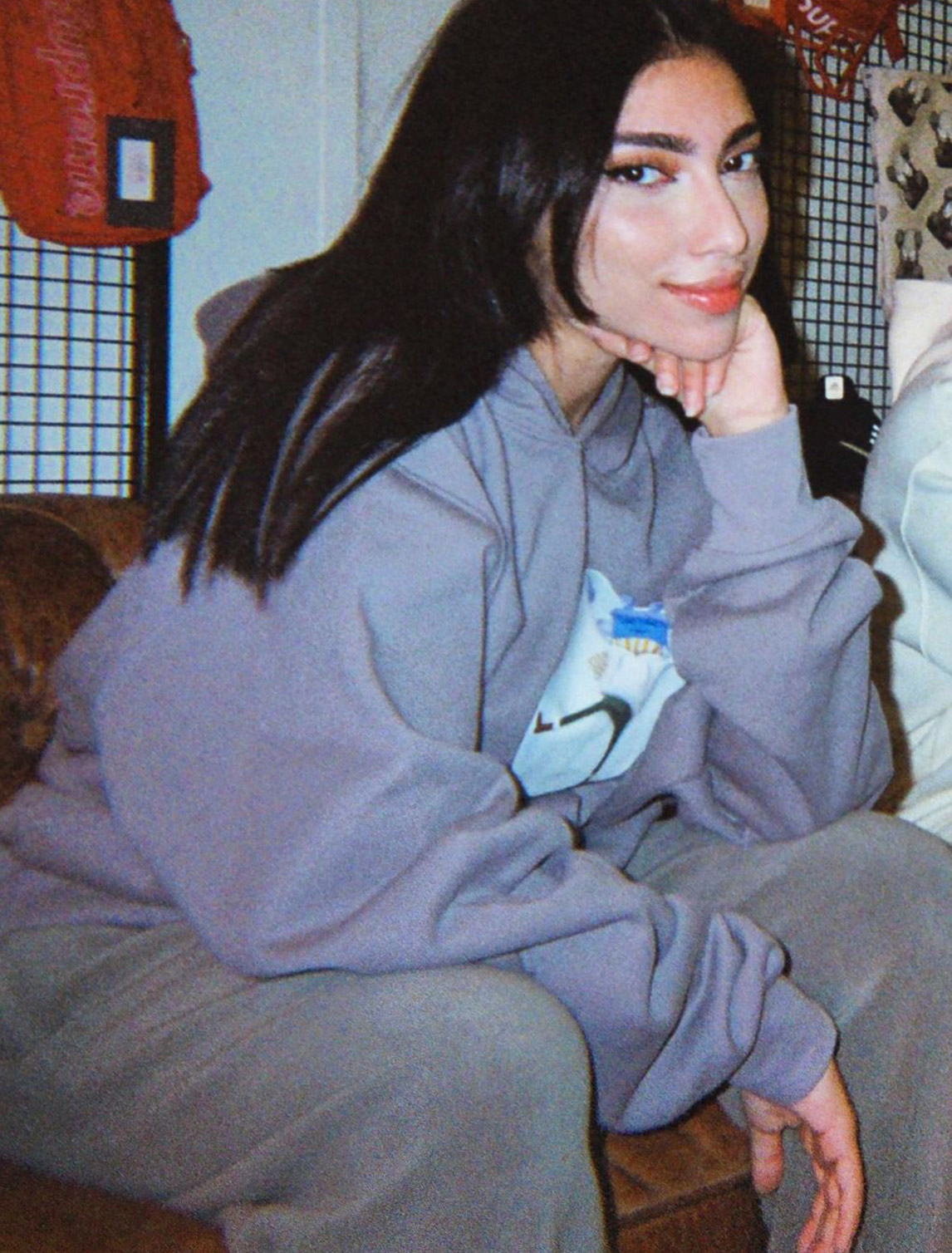

What is it like to break down barriers? Middle Eastern racing driver Amna Al Qubaisi studies, models and roars around a racetrack. We find out more

By Katy Fairman

As a young child, when my parents had their friends over for dinner parties, conversation bounced between their boring jobs, politics or world news. However, for Amna Al Qubaisi, the guests her father bought round for dinner was what led her to fall in love with motor racing. Now a successful racing driver in her own right, Amna is rewriting the rules in the Middle East for women and helping inspire the next generation to follow in her footsteps.

Born into a motorsport-mad household, Amna is one of four siblings. Her father, Khaled al Qubaisi, is also a professional racer, but in an unusual twist it’s both his daughters that have chased the same career as him and not his sons. “He was actually very supportive and shocked,” Amna says when she first told her father she wanted to give racing a go, at age 14. “He expected my brothers to ask him to take part in the sport.” Her two brothers did give karting a try. The youngest decided it was too hot to drive and he would sweat too much, whereas the other labelled karting “an aggressive sport”, which is rather ironic as he now does kickboxing.

Amna was taken to a karting track, and coached by her father on all the things she needed to know. Around that time, an academy was looking for drivers that had the best time, with no judgement on who set the laps and no concerns about your age or gender, for example. “They just picked the top 20 from a list with the best times. And I was among that top group,” says Amna.

From there, Amna and her sister Hamda, continued to keep racing in the family. In 2022, they even took it to another level, competing in the Formula Regional Asian Championship – alongside their father. “It was actually a really tough experience. My father defends his position really well, Amna says. “It was really hard to compete with him, but he’s also quick among my other teammates, so it was very challenging. My sister as well. We were very competitive on track. We’re always either behind each other or one of us is in front of the other, and we always finish behind each other on the racetrack.” With racing being such a family affair, Amna also can’t switch off between races if her on-track rivals are sitting opposite her at the dinner table. “We had a lot of arguments and fights,” she remembers. “One time I got really mad at my sister because she had a problem with her car during a race. I was behind her and we were fighting for eighth place and she was blocking me when she had the problem.

“After the race, I was screaming at her and we argued even when we arrived back home. I was like ‘I could have finished in eighth but because of you I finished tenth’. So we were arguing big time.”

However, as much as motorsport is one of her passions, reality means most people can’t spend all day racing around in circles and expect to pay the bills. Therefore, Amna headed off to university to study. Records management and archival sciences was the major Amna opted for; the course offered a deeper insight into record-keeping and encompassed other elements such as coding, finance and programming. Nevertheless, prioritising education meant sacrificing some pretty big racing opportunities. “I wanted to compete in the W series,” Amna explains. The W Series is a free-to-enter championship exclusively for women, with a big prize pot to be won at the end. It’s also currently part of the F1 calendar, and is gaining more attention every year.

speed

“During the selection time [for W Series] I had exams and it was very difficult for me to talk to the staff and the head of department at my university. They were very strict and they told me ‘It’s either you do these exams or repeat the whole year’. I didn’t want to do the whole year again so I was just like, ‘that’s it, it’s fine, I’ll just do the exams’.”

Finding the balance between university and racing has always been a challenge. “It’s very difficult to be in between the two. I had the last-minute call to race in Europe for the last two rounds of a championship, and during that time I was in my first semester. I had to be away for two months and my university takes attendance very seriously.

“I tried taking my courses online, but with the time difference I’m always either at the gym, with the team or at the simulator. So it was very difficult to balance, but it was manageable. I had to make my university peers and staff understand that I’m taking the sport seriously. Eventually they understood and they were able to give me an athletic programme at the university. So even if I missed a few classes, I could do the exams and if I passed them, then I passed the whole semester.”

Amna also touches upon the stereotypes that come with racing drivers from the Middle East and how some journalists often don’t feel very supportive or understanding. “People immediately assume that we have a lot of money, which is why we’re taking part… like it’s easier for us to enter the sport.” In fact, as Amna explains, it’s just the opposite. Like most racing drivers, she’s frequently running around to find sponsors or spend as much time on the racetrack as possible. “I don’t think people could understand the fact that, even though I’m a woman and I come from the Middle East, I’m not a multi-billionaire. I’m just like any other female driver.” And being a woman in motorsport is no easy task. Although times are changing, it’s still very much a man’s world. The last woman to take part in a Formula 1 race was Lella Lombardi in 1976, and the paddocks are still made up with a large majority of men.

“At the very beginning, it was very difficult. Being the only girl, my team was left out. I was very young and I felt like an outcast. But as the years went by and I started to do well in my career, I started to make friends and people were nicer to me.” “Another reason it was hard to make friends was because I’m from the Middle East. In my days of karting I dealt with racism. There were a few times when I thought I should stop racing, I didn’t see the point of it. People are very political about it and it is a sport which doesn’t involve politics.” The same day as our interview, the FIA, the governing body for Formula 1, placed a ban, from 2023, on drivers making political, religious and personal statements or comments without written permission. The move sparked a lot of outrage from fans with a landslide number of people disagreeing with the change. However, Amna has a different take on the rule.

“I think it’s for the better. It takes away from all the drama, from people causing hate toward each other for no reason. So I think it’s good – we’re all just focusing on sports and that’s the main thing. We shouldn’t really comment on anything political or religious.”

As well as continuing to challenge the ‘norm’ as a woman in motorsport from the Middle East, Amna still enjoys the same passions as most her age. Fashion is a big love in her life, so appearing as a cover star on Harper’s Bazaar Arabia last November was a dream come true. “Since I was young I have loved fashion and makeup but I have never got involved in it – I’ve tried to stay professional. However, just recently when I wasn’t racing I got invited to events and a few brands have reached out to me.”

When she’s not modelling beautiful designer garments on magazine covers, Amna’s personal style is a bit more relaxed. “I really like street style. It’s something I wear all the time, but I also like the DuneCore style. It’s too hot to wear it here, but I’ve tried out the style occasionally at parties or other events when they are indoors!” As a woman from the Middle East competing in motorsport, it’s fair to say Amna is helping rewrite the rules, something she’s been recognised for at ‘The Most Creative People In Business’ Awards.

“There are families that are very close minded and don’t really let their daughters do specific sports, or take specific studies, because they are known to be male dominated. So when I broke that barrier by competing in motorsports, I had a lot of women reach out to me and tell me that I was the reason why their father had allowed them to do something specific. “I felt happy that I had broken that traditional family rule that says women aren’t supposed to be intruding in a man’s world.”

Editorial Design by this is root

Title Image by Rima Wehbi