Fearless In Finland

Icy tracks and scary skids are no problem for Finland’s new breed of female rally drivers. We find out what it’s like to race with the country’s young drivers

By Alex King

Photography by Ossi Piispanen

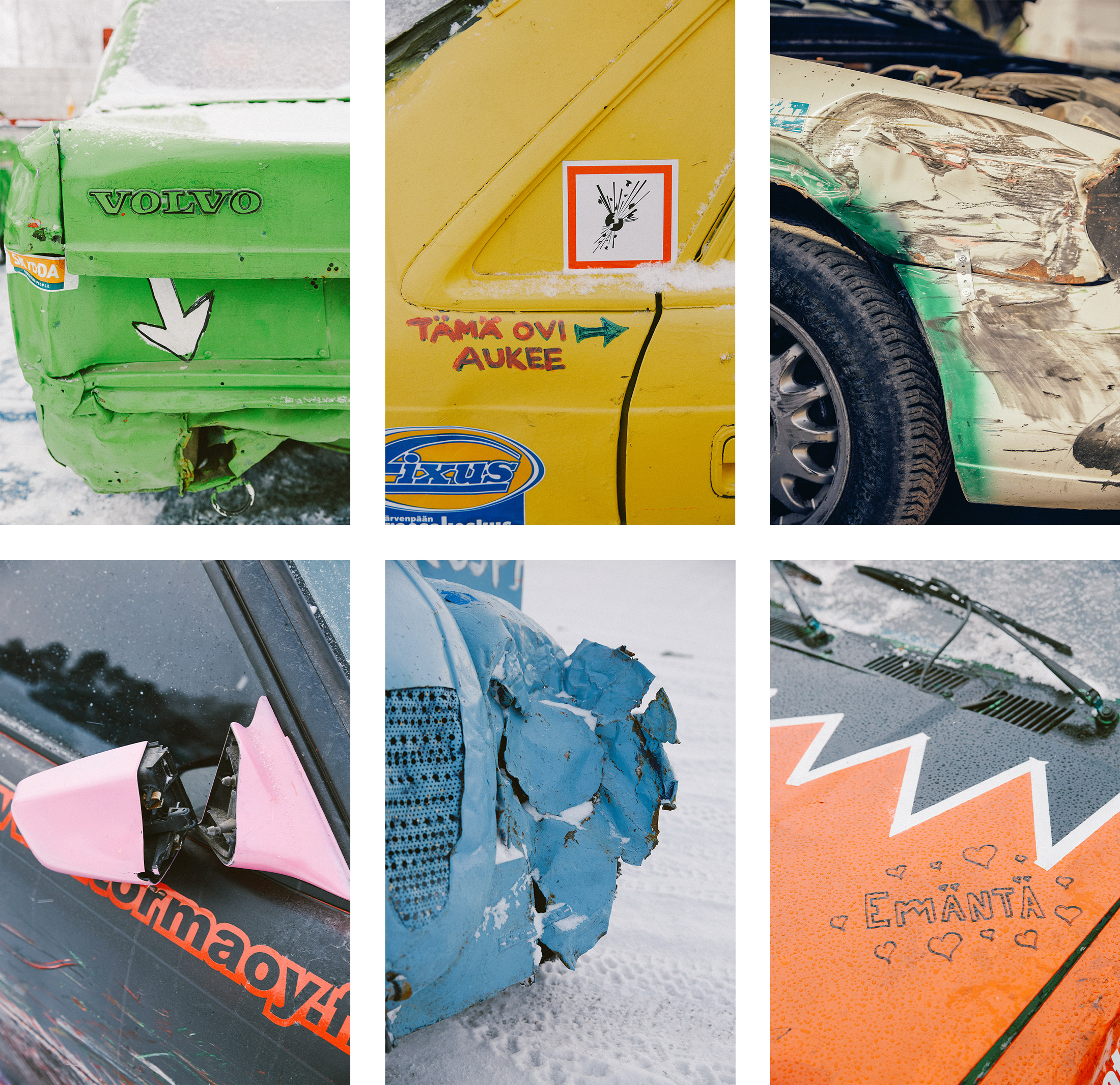

A bizarre collection of battered and brightly coloured cars are lined up side-by-side on a makeshift starting line. We’re in Pihtipudas in central Finland for the semi-final of the Rokkiralli junior series. The roar of engines and whoops from spectators massed on the banks around the track drown out the usual tranquility of the surrounding forest. Noora Savela, 17, is revving the engine of her blue Mazda 626, whose appearance has changed over the years after repeated bumps and dents from crashing and racing. Noora has christened the car Luotto 626 (which translates as ‘Reliable 626’) and covered it with hand-painted drawings of her favourite cartoon characters. To both sides are more teenage racers, whose hand-built and hand-painted vehicles look equally un-roadworthy.

The starting light turns to green and Noora floors it. Her misshapen Mazda hurtles forward, throwing up dust in its wake. Noora realises she’s in first place as she approaches the first bend. When she turns into the corner, her car begins to drift sideways as she’s shunted by the one behind, pushing her out of the turn and into the sandbank at the edge of the track. The Mazda is launched into the air, flipping three times. “When you lose control, you don’t realise what’s going on at first,” Noora reflects later. “It was a dry day and super dusty: I couldn’t see anything at all. Then at some point, you realise you’re no longer facing the right way up. It’s a bit scary.”

Eventually Noora’s car stops flipping and comes to rest – miraculously – on its wheels. But it’s obscured by the huge dust cloud kicked up by the car as it ploughed through the side of the track. The dust begins to settle and Noora stumbles out of the car, visibly shaken. She brushes herself off as the race is called to a halt – standard practice in the junior league when a racer flips their car. Noora is whisked off to the paramedics for a compulsory check-up. While she’s sitting in the ambulance, her car is given a post-crash safety check and Noora’s team of family mechanics get it ready to make the start line again later that day. “After the crash, it was scary coming into the first bend: it’s always really fast and all the drivers are taking huge risks to get into the lead,” Noora says. “I took the start a bit slower for the next few races. But soon enough, I overcame the fear.”

Rokkiralli is a Finnish DIY rally series that is certainly not for the fainthearted. Unlike the professional rally leagues where successful drivers need to spend huge sums to put themselves in contention, no Rokkiralli driver is allowed to spend more than €650 on their car. Keeping the big money out maintains a level playing field and keeps the focus on racing in its purest form. It also makes rally accessible to everyone: from oddball petrolheads to larger-than-life characters, but also women and girls. Yet, it’s not just the low price of entry that makes Rokkiralli the most inclusive rally series in Finland: a huge emphasis is placed on making the series raucous fun and inviting to all. If you can race, you’re part of the Rokkiralli family.

ACCESSIBLE

The summer Rokkiralli meets go off with a carnival atmosphere of skids, spills and silliness in the pits. But when winter rolls around, Rokkiralli becomes an altogether different beast: a sub-zero spectacle of racing skill and spectator endurance. Once the ice freezes thick enough, racers assemble on frozen lakes across Finland to put their bargain basement machines to the ultimate test. The settings are idyllic: often surrounded by snow-topped fir trees and quaint wooden churches. But on the improvised tracks and in the pits, things are anything but serene: it’s a cacophony of revving engines, frantic last-minute repairs and Finnish racing banter.

ENDURANCE

“There are fewer winter races each season because they struggle to find enough people to organise them but it’s a nice change to drive on ice,” explains Noora, who recently turned 18. “Racing on ice with studded winter tyres is a completely different experience. There’s very little grip on the track, so it’s much harder to control the car. But the importance of your car’s power decreases in winter.”

The frozen surface is a leveller: your car matters less, while the challenge of just staying on the icy track separates out the Sunday drivers from the serious racers. On the ice, Noora thrives. After competing in two seasons since she began racing in 2019 (the 2020 season was cancelled due to Coronavirus), she placed highest on the ice, coming in third in Saarijärvi – home turf – in winter 2021.

Rokkiralli was founded by a notorious figure from the Demolition Derby scene, Kristian ‘The Sheik’ Laakso, in 2000, when 28 drivers set out onto the frozen lake outside Kouvola in southeastern Finland. The women’s and junior series were added in 2004 and have ballooned in popularity to around 60 women and 40 teens competing in a total field of over 250 for the 2021 summer races.

“The basic principles of Rokkiralli are togetherness and having fun,” explains Mirtsu Heikkilä, who has been racing aggressively – and crashing regularly – since the very beginning. “We try to keep the sport cheap and easily accessible for everyone. Life in the pits is amazing: in summer we sit by the fire, blast out rock ’n’ roll and talk about the day’s racing. We have met loads of people and made friends through racing. It’s like a family event for us.”

Noora’s uncle took her to her first Rokkiralli event and now the whole family race and maintain their cars together. “We started building a car and the rest is history: it’s very addictive,” Noora explains. “As we grow older, we spend less and less time together. But the best thing about having a family team is that this shared hobby brings us together. Everyone puts aside their other commitments and makes time for rallying. It has brought our family closer.”

Even Noora’s younger sister Ilda, 17, who used to sit in the pits glued to her phone, now has her own car and began racing in the 2021 season. “Of course our sister dynamic is important and I hope she does well,” Noora says. “But if there is a situation where we are in the same heat and only one can win, it will get competitive!”

TEAM SPIRIT

Noora has grown closer to her own family thanks to Rokkiralli but also found a new family among her fellow women racers. “We girls have a really good team spirit both inside and outside of racing,” Noora explains. “The older women’s league drivers also give us a huge amount of support.” Spare parts and experience are often shared between racers and if someone has a mechanical problem that prevents them from racing, the teams in the pits will usually come together to lend a hand and see if they can get them back on track.

Up until age 18, teenage racers like Noora and Ilda race in the mixed junior league. Then they can choose to race in the women’s league or the main competition. The boys they race alongside in the junior league compete to have the most ridiculously decorated cars, which often include badly drawn penises. But even among the awkward adolescent boy contingent, there’s a family feeling that resonates through everything – and despite all the dick jokes and pubescent humour, young women like Noora are actively made to feel included.

COMMUNITY

“I don’t feel like there’s a big gender divide in the pits, we get on well with the men and boys,” Noora says. “All the boys are super nice, lend their support and congratulate me if I beat them. It’s nice that the boys dare to joke and include us girls in the banter. It’s part of the atmosphere and the culture. It makes you feel like you are part of the community.”

There’s little debate that the teenage girls are just as fast as the boys: that was settled long ago by Taru Mikkonen, 19, one of the best-known Rokkiralli drivers. Taru went from dominating the junior league to beating adults in the same car. “Rally is a male-dominated sport and they say women can’t compete, but we’re often better than the men,” Taru says with a cheeky grin. “Young girls in the crowd look up to me but many don’t dare to race. I’ve always tried to encourage them to be brave and show people what women can do. Boys are too hot-headed, so while they’re crashing into each other, I overtake them all… and they get annoyed when they lose to girls, so that feels great.”

Taru is one of many teen Rokkiralli drivers whose racing success has left them considering trying to break into the pro circuit. As for Noora, right now she’s focused on finishing high school in Saarijärvi, central Finland. She’s not sure what she wants to do next but she knows she wants to stay connected to cars – maybe as a mechanic or automotive engineer. “I have been driving ever since I could reach the pedals and the steering wheel,” Noora reflects. “My family instilled a love of cars in me and they have become an essential part of my life. Racing has really boosted my self-confidence. I know I can race just as well as the boys – or anyone else for that matter. If there are people who still think racing isn’t for girls, I would tell them to look at the rankings – then join me on the start line.”

Editorial Design Root