Art: Project Backboard

Project Backboard is proof that sport and art are two of the most universal languages we have. The world over, amazing artists are transforming basketball courts and bringing communities to life

By Glorious

Project Backboard was founded in 2015 in Memphis, TN. It was originally an effort to simply add game lines to the basketball courts in public parks that had none. Soon after, Project Backboard began incorporating artwork into courts when Memphis artist, Anthony Lee, created a design for an entire court (instead of just advising on colours for the game lines and keys) to match the sculptures he had previously installed next to the basketball court. From there, the idea of using public basketball courts as a canvas and collaborating with local artists was born and ultimately led to what Project Backboard is known for today. We chat to Project Manager Alyssa Barnes about the process for each project and the joy each court brings to its community.

Glorious: What attracted you to the work of Project Backboard?

Alyssa Barnes: Somewhat serendipitously, I became involved with Project Backboard in late 2020. As a former collegiate athlete and creative with a background in art direction and design, I’ve always looked for a way to stay at the intersection of art, design and sport. I knew of and admired Project Backboard, but never quite knew how to get involved. I happened to see an artist’s social post about needing local volunteers to paint a basketball court in Knoxville, TN, so I immediately reached out to say that I would love to help, and I was willing to travel from my home in Boston. When I arrived, it turned out that it was being led by Project Backboard. I meshed really well with the team, which was easy because they were so welcoming, picked up on the process quite quickly, and fell in love with the work through that experience. I’m now designing for the organisation and leading projects with a particular focus on female athletes and artists.

Glorious: How is Project Backboard funded?

Alyssa Barnes: Projects are funded in a few different ways. Some projects come to us fully funded by brand sponsorships or ongoing partnerships, while others are funded by local community fundraising efforts and grants. We also have individuals or communities reach out to us directly and we are able to help them to create a fundraising plan and/or put a funding request out to our network of partners.

Glorious: What is the process for each project from commissioning an artist through to installation and completion?

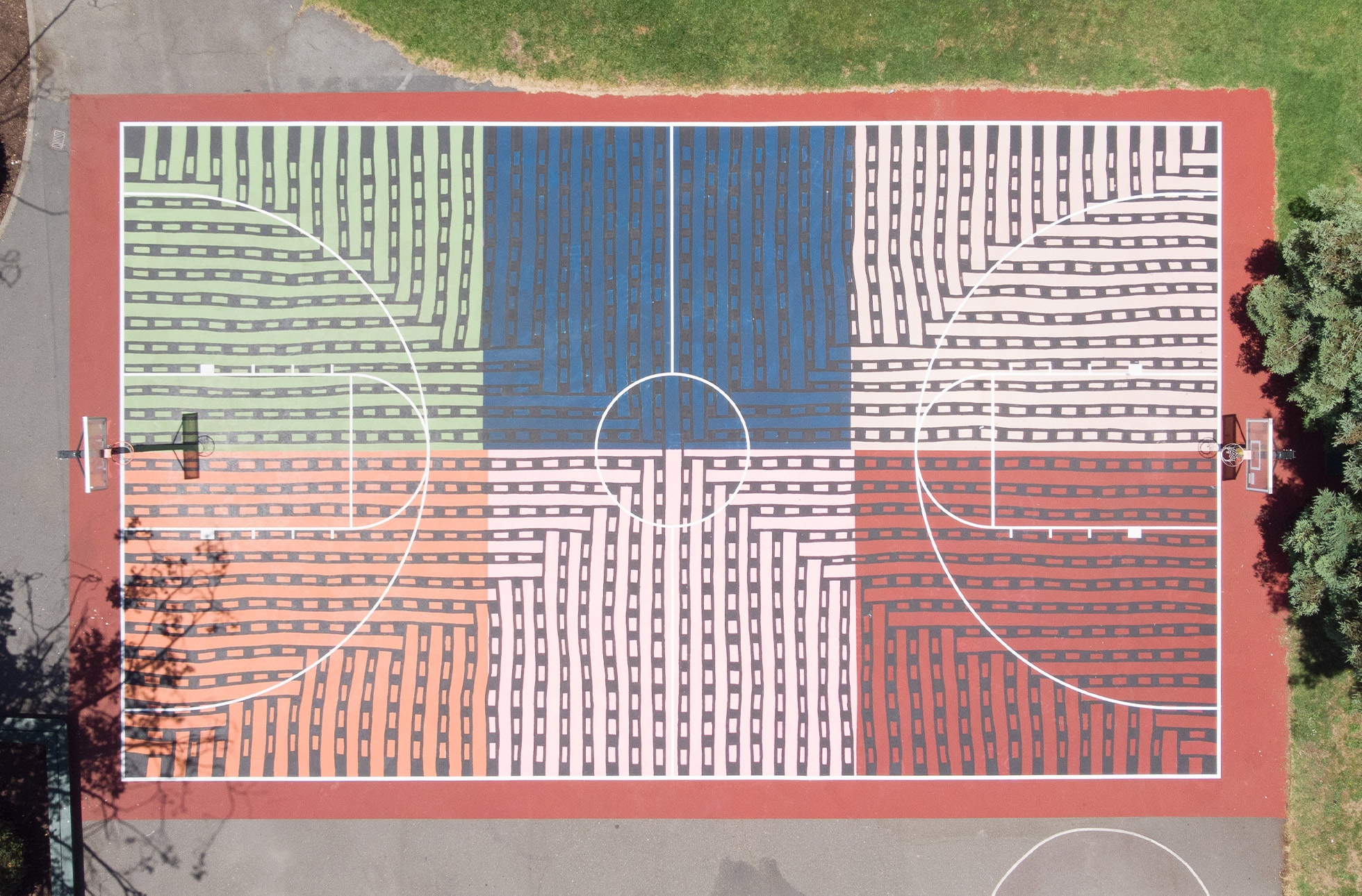

Alyssa Barnes: We always try to be intentional when it comes to selecting an artist for a particular court. Typically, we try to find an artist who has ties, a connection, or is from the community where the court is laid. We want the court to feel meaningful to the community and we try to involve the community in decision-making as often as possible.

CONNECTION

Timelines for projects always vary. There are some projects that have been in the works for years, while others come about quite quickly. In terms of process, once we have approval and permits from the city and approved artwork, we prepare the artwork for installation, order supplies, and assemble a team. We have cultivated a great network of team members across the country with people in LA, New York City, Boston, Baltimore, and beyond.

We also try to bring in members of the community who are interested in volunteering and we’ll hold volunteer/ community days when possible. For me, those are truly the best days. It’s so rewarding to see the genuine interest and excitement from the community to be able to join us in painting. Once we’re on site, installation takes roughly 5-7 days depending on the complexity of artwork, number of courts, and of course the weather.

Glorious: What are the criteria for selecting an artist, or do artists approach Project Backboard?

Alyssa Barnes: It’s important to find an artist who is either from the community or has a connection to the community so that there is an authentic story to tell. For me, authenticity, the story, and being intentional are the things that matter most when it comes to selecting an artist. Artists do reach out to us, and there are also so many amazing artists and designers that I admire, so I am always looking for opportunities that would make sense to be able to collaborate with them, or see their artwork brought to life on a basketball court. Corita Kent, Ellsworth Kelly, and Stuart Davis are all artists on my bucket list. While at galleries and shows I find myself looking at art through the lens of how it could translate to a public space. I find myself now, looking at art while at galleries and shows, through the lens of how it could translate to a public space. In the future, I would love to think beyond the basketball court and more about how we can bring in more sculptural elements and playscapes into these public spaces as a way to make them more immersive and attract even more people.This would in turn open up opportunities to collaborate with more artists in a wider range of mediums.

PASSIONATE

Glorious: Do you work collaboratively with an artist, ie do you give them a brief, or do they have free rein?

Alyssa Barnes: We try to let the artist have free rein to create what they think will best serve the community for which the artwork is being created. An artist will either create an original work for the court and community, or will choose to use a piece from their existing body of work.

Glorious: How long does each project take and what are the challenges?

Alyssa Barnes: Once the court has been resurfaced and our team is on site, installation ideally takes about 5-7 days depending on the complexity of artwork and number of courts. There are instances where it takes longer because there is almost always something unexpected to navigate once we’re there, but, I love a good challenge or problem to solve. I’ve had stencils tear and had to make my own on site, tools have broken, supplies haven’t arrived on time, we’ve run out of paint, and it’s almost guaranteed that people will walk through wet paint (guilty!)

However, the biggest challenge we face is weather. Other challenges we can figure out as a team, but when it comes to weather, it’s ultimately out of our control and sometimes we have to just wait it out. We’ve had days where the heat index soared over 111 degrees in Moss Point, Mississippi forcing us to stop working between the hours of 12-2 because we were literally melting. And while in Sitka, Alaska, it did not stop raining, so the team constructed a makeshift tent over the entire court in order to stay dry and finish on time.

Glorious: Is there a team of people that work on the installation or is it just the artist?

Alyssa Barnes: For an install we usually bring a team of 5-6 for each project. Our amazing team members are located throughout the country and like myself, many of them do other work in addition to Project Backboard, so who we bring depends on availability and location. We also try to allow people to be a part of projects that they are personally passionate about, so either an artist or an athlete they admire, or a location they are interested in or have ties to.

Glorious: In your opinion, what has been the biggest project and the one that has received the most media attention and why?

Alyssa Barnes: I would say the Faith Ringgold court because she is such a legend and there is a fascinating story behind that court.

(1) it is located in Harlem, the epicenter of outdoor basketball

(2) CUNY originally rejected her proposal to gift them a free mural, so instead she went on to paint the mural for the women’s prison at Rikers. The court now being in the shadow of CUNY’s campus, corrects a historic wrong

(3) It was the first court renovation that was done with funds from the sale of Common Practice, (4) It was also recognised in People Magazine as #6 on their Travel List: 25 Things to Do, Eat &See This Year!

COMMUNITY

Glorious: Community is clearly at the heart of what you do, so tell us how some of these projects have enhanced a community and people’s lives.

Alyssa Barnes: It has been so rewarding to see the immediate impact the work we’re doing has on a community. It brings people out and together, and provides an opportunity for new connections to be made and new experiences to be had. One thing I notice, and find the most meaningful, is when we have opportunities to connect with the local community directly while we are on site painting. People love to come out and share their appreciation for what we’re doing, ask if they can help, or just learn more about who we are and what we’re doing. Everyone typically is so welcoming and truly supportive. Not only are we able to create spaces that inspire, but there are opportunities to activate them and create experiences that, I hope, are also inspiring and memorable.

While leading the renovation and installation for the Paige Bueckers and Jamad Fiin court, in partnership with StockX, we planned an afternoon of drills and games with a local girls’ youth team. Seeing their faces light up as they got to hoop it up on the court that we had just finished painting with two amazingly talented athletes they admired, was absolutely everything.

I also notice that when we renovate courts with artwork, it brings new life and energy to the space, and starts to bring new people to the court who may not have been there before. You begin to see more families and more women and young girls because the use of art and colour makes the space feel more vibrant and welcoming. My hope with incorporating artwork onto these courts is that they will feel more accessible and inclusive for all to play and will inspire those who may have never played basketball before, to try something new.

Glorious: The combination of art and sport is very powerful, but how would you describe this based on your experiences since Project Backboard was established?

Alyssa Barnes: Sport and art are two of the most universal languages we have. Many of us share the experience of growing up without seeing a lot of examples of individuals who were both artists and athletes. It always seemed as though you had to choose to be one or the other. Part of what we are doing through this work is showing people that you can be multidimensional. You don’t have to choose to be identified as one thing. You can be both an artist and athlete, and in many ways, they aren’t all that different from one another.

Glorious: Does this concept only exist in the US or has it been rolled out in other countries?

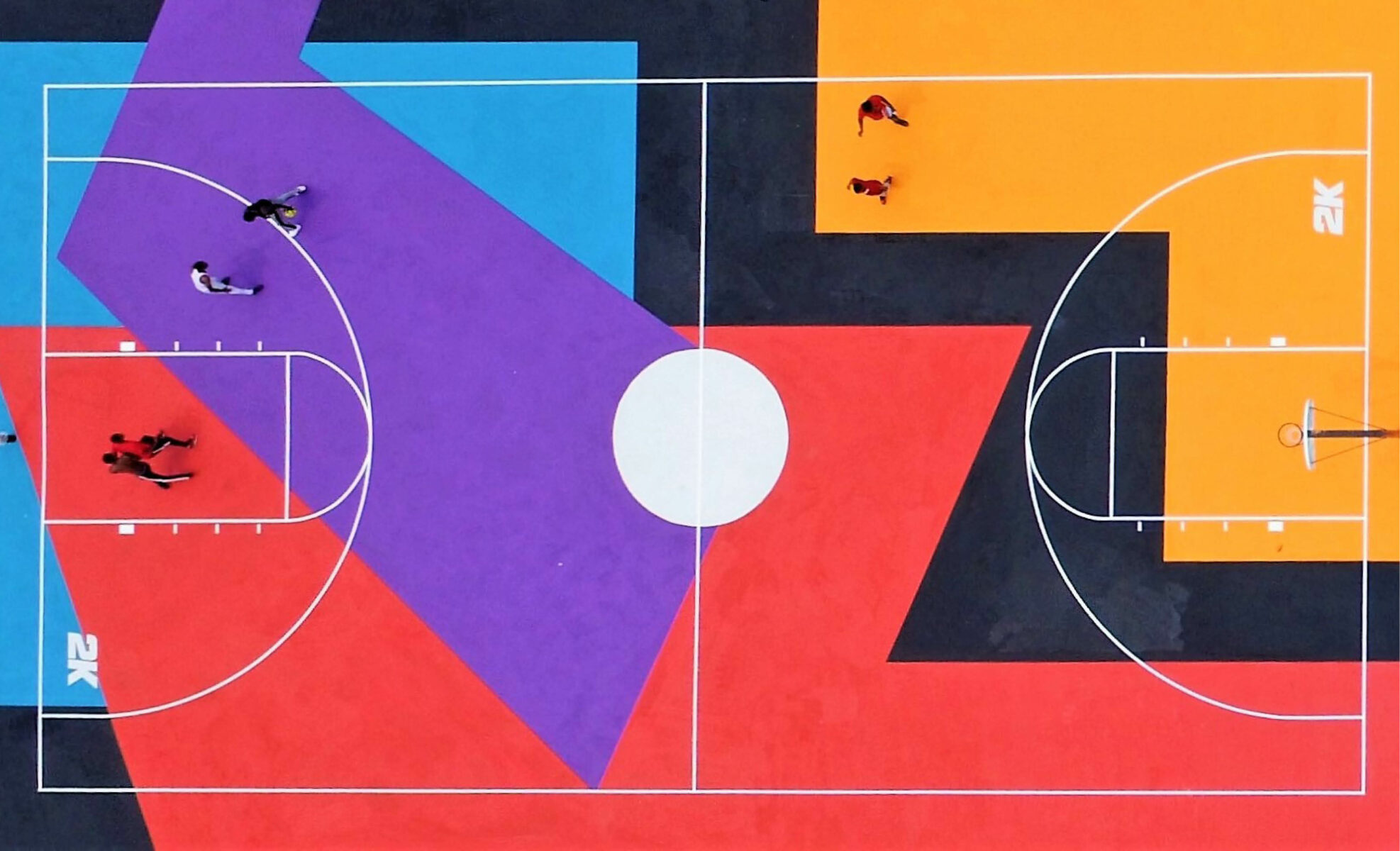

Alyssa Barnes: This concept definitely exists abroad. There are quite a few beautiful and well-known courts around the world. We have also installed and painted a handful of courts outside of the US and have goals to continue to support more work internationally in the coming years.

Glorious: Another arm of Project Backboard is the book Common Practice: Basketball & Contemporary Art. Tell us about this book and where can we find it?

Alyssa Barnes: Common Practice is the original book and this is the third in the series that expands the world of Project Backboard beyond physical courts and uses the intersection of art and basketball to create community impact through curated programming, exhibitions, artist collaborations and publications. The hope with Common Practice is that the ideas and concepts we are exploring through Project Backboard reach a wider audience, and an audience beyond just the folks who get to hoop on one of our courts. All purchases made through https://commonpractice.online/ go to support Project Backboard.

Glorious: What’s next for Project Backboard?

Alyssa Barnes: Of course, we want to keep renovating more courts in more communities while also pushing ourselves to continue to get better and better each year. We are constantly learning more and new ways to improve and take pride in the quality of our work and the commitment to the integrity of the art and the artist. We’ve also had several conversations, exploring the idea of building an online community and providing more resources for those who want to renovate courts in their own communities.

Editorial Design by this is root

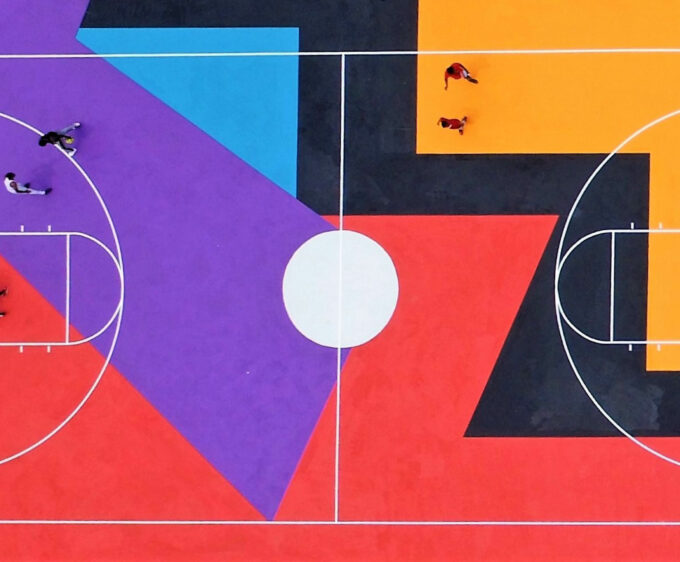

Title Image – Adrienne Gaither, Lincoln Recreation Centre, Cincinnati, OH (2019).