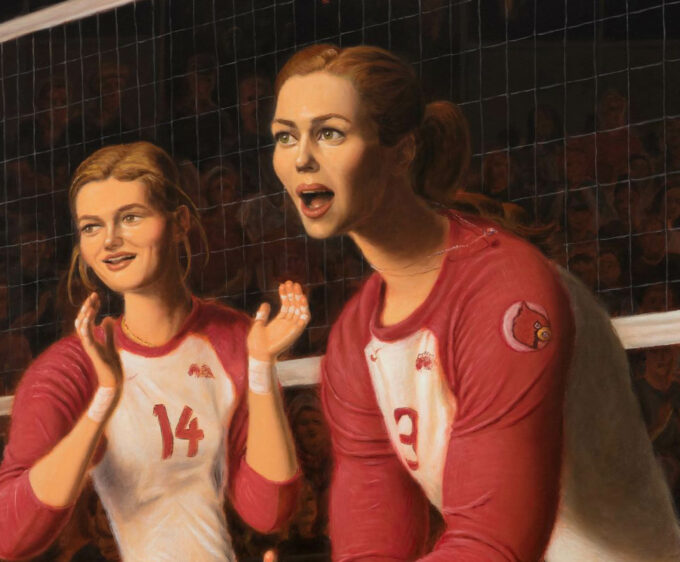

Art: Martin Schoeller

“Why shouldn’t women train their muscles? Why are women supposed to look weak?” Photographer Martin Schoeller captures the strength and dedication of women bodybuilders

By Diane Smyth

Photography by Martin Schoeller

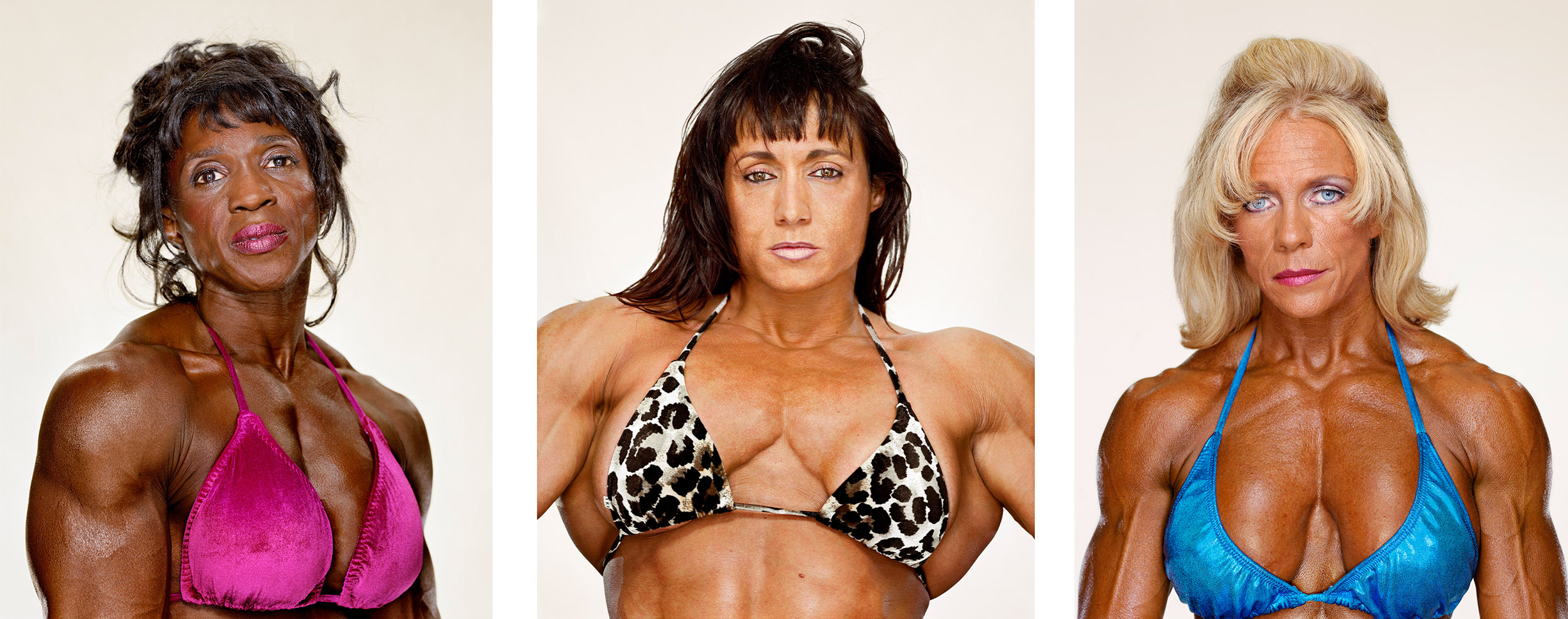

“I was so intrigued by these women and the questions that came along with them,” says Martin Schoeller. “Why would a woman be willing to put so much time and effort into bodybuilding? Being big is something many people find unappealing or unfeminine, having muscles is associated with looking manly. But talking with the female bodybuilders, I found their arguments fascinating. Why can’t women be muscular? Why shouldn’t women train their muscles? Why are women supposed to look weak? I loved the self-confidence and their dedication that came across. And visually speaking, it was amazing.”

We’re discussing his series ‘Female Bodybuilders’, which he started in 2003, when an assistant dragged him along to a bodybuilding competition. Immediately curious, Schoeller went on to attend elite competitions for the next five years, photographing female contenders from all over the world; by the time he had finished he had shot 66 women, practically the whole scene at the time. In 2018 he published the work as a book, including an artist’s statement which vigorously defended the women’s right to do what they wanted, in the face of fierce criticism from mainstream culture.

“Many of the subjects in this book raise children, maintain marriages and pursue full-time careers, while straining the natural capacities of the human body,” he wrote. “In the process, they risk easy ridicule from people outside of their tiny competitive community. They challenge the boundaries of not only the shifting, maddening and ruthless standards of the female beauty industry, but of what constitutes ‘(un)natural’. For many observers, the outsized development and hyper-articulation of these ladies’ every muscular detail, present an affront to acceptable standards of femininity, of beauty, of taste.”

“I felt very protective of them,” he tells me. “I got really mad at all these stupid comments whenever I showed the images.” Still, he happily admits, competitive bodybuilding is hardcore. To achieve the look, the women adhered to ruthlessly strict dietary and exercise regimes, and many also took steroids and drugs. Before competitions they would starve and dehydrate themselves to trim off residual moisture or fat, some even taking diuretics to this end. Spray-tanned to emphasise their muscles, some then took more drugs to pump them up still further.

The women only looked this way for the duration of the competition, Schoeller explains, and were often quite weak and disorientated because of it; he doesn’t condone the damage but points out that male bodybuilders were the same, yet met nowhere near the same level of criticism. For him, the difficulties they faced just made these women more extraordinary, enduring so much in pursuit of an ideal shared by so few. And the fact they also looked unusual was just as important. As he puts it: “Anyone who doesn’t fulfil our expectations of what people should look like is always more interesting.”

Schoeller hired a room at each venue he attended, taking along three assistants and his large-format film camera; he lit each shot with an array of 16 lights and, because of the limitations of his old-school camera, had to ask the women to be quite static. But he tried to help them relax, spending about 45 minutes per portrait and starting each session by playing music and talking. The women would do their own makeup and decide which one of their bikinis they wanted to wear, while Schoeller asked them about their muscles and which ones they wanted to show off. Other than that, they were free to present themselves as they chose.

He looked for moments in which the women were resting, rather than visibly posing, keen to get something unforced and to record each individual impartially. He felt compelled to build a catalogue outside the range of judgement, he writes in his book, not to celebrate or condemn but “merely to show”. “My goal is always to document people,” he tells me. “People just end up looking the way they’re looking in real life. Too often we alter reality.” Later he adds he was hoping to capture a “spirit of open-mindedness”.

It’s a sentiment that runs through Schoeller’s work, whether he’s photographing President Barack Obama or exonerated Death Row prisoners, Angelina Jolie or older Holocaust survivors. Born in Germany in 1968, he moved to New York in the mid-1990s and is now one of the world’s best-known portrait photographers, working for titles such as The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, TIME, and The New York Times Magazine, and winning awards for his advertising work. He’s also published eight books, and exhibits his images around the world.

Shooting on commission or a much longer-term personal projects, working with a celebrity or someone much more obscure, Schoeller’s photography has this sense of clear-sightedness, this commitment to looking without judgement. He often focuses in on the face, in fact, stripping away the clues of his sitter’s clothes and surroundings to find something more essential; his images are often shown large in size and, though Schoeller argues the lighting is soft and the shallow depth-of-field flattering, he admits his gaze can be unsparing.

Powerful

Skin texture is held up to scrutiny, flaws are soberly recorded and, in the case of the female bodybuilders, cracks in the fake tan are clearly shown. But to Schoeller, these supposed imperfections are part of the person and make for something more interesting than the heavily filtered images shared on social media, or the painstakingly retouched shots reproduced in more aspirational magazines. To him, the apparently picture-perfect is just boring, and makes everyone – particularly women – look the same. “I’m not trying to make people look bad,” he says. “They look like themselves.”

And anyway, he points out, what’s perfect is in the eye of the beholder; his introduction to ‘Female Bodybuilders’ urges his readers to question their own reactions, and asks, “If a subject is proud of the way she looks, whose discomfort are you feeling?” More recently he shot footballer Megan Rapinoe for a Nike campaign, an athlete whose cropped hair rejects tropes of femininity which even the bodybuilders still followed.

Schoeller says that Rapinoe and the other female footballers he shot for Nike were great to work with, because they were relaxed, outgoing and fun – less concerned with their appearance than the average actress or celebrity. In general he loves shooting athletes, he says, because it’s “speedier to get an honest expression”; the Nike campaign also shows how fast things have moved on since Schoeller finished the bodybuilders, though, because assumptions about gender have undergone seismic shifts in the intervening 15 years. Back in 2008 female footballers didn’t get much publicity.

Schoeller has explored some of these shifts in his commissions, shooting drag queens for New York Magazine and LGBTQ celebrities for Out Magazine; he’s also overstepped the boundaries in less obvious ways, photographing leaders such as Angela Merkel, who was Germany’s first female chancellor. In 2012 he shot a story for TIME magazine on attachment parenting, which included a cover showing Jamie Lynne Grumet breast-feeding her three-year-old son. The coverline asked, ‘Are you mom enough?’ and Schoeller chose to show the child standing up “to underline the point that this was an uncommon situation”.

His recent commission for National Geographic focused on the Kayapo women of the Brazilian rainforest, who have very different conceptions of female presentation to the West. Schoeller often uses his Instagram account to show series such as these together, typically adding a quote from each individual to give an insight into their particular perspective. “The persona is inspired by female superheroes, shady, bitchy ladies from anime and cartoons,” reads a quote from drag queen Acquaria. “I always felt like I could relate to the super strong.”

And, while gender is far from Schoeller’s primary focus, in photographing groups of individuals across time and around the globe, his work naturally questions our norms, the assumptions so embedded we forget them. It’s one of the reasons he likes working in series, in so-called typologies that pick out shared standards. “I want to document people of my time,” he says. “But there’s got to be a substantial amount.

“It’s got to be a real statement,” he continues. “If you followed 80% or 90% of the group of people involved with an activity, then you can say ‘Yeah, this is really what these people looked like’.” And, as the female bodybuilders show, those standards evolve and mutate, and even disappear. Female bodybuilders don’t look like the ones in his shots any more because the culture around doping has changed; in general, he says, they’re not as big now. “I caught them at the height.”

Editorial Design Root