Why I Get Up at 5AM

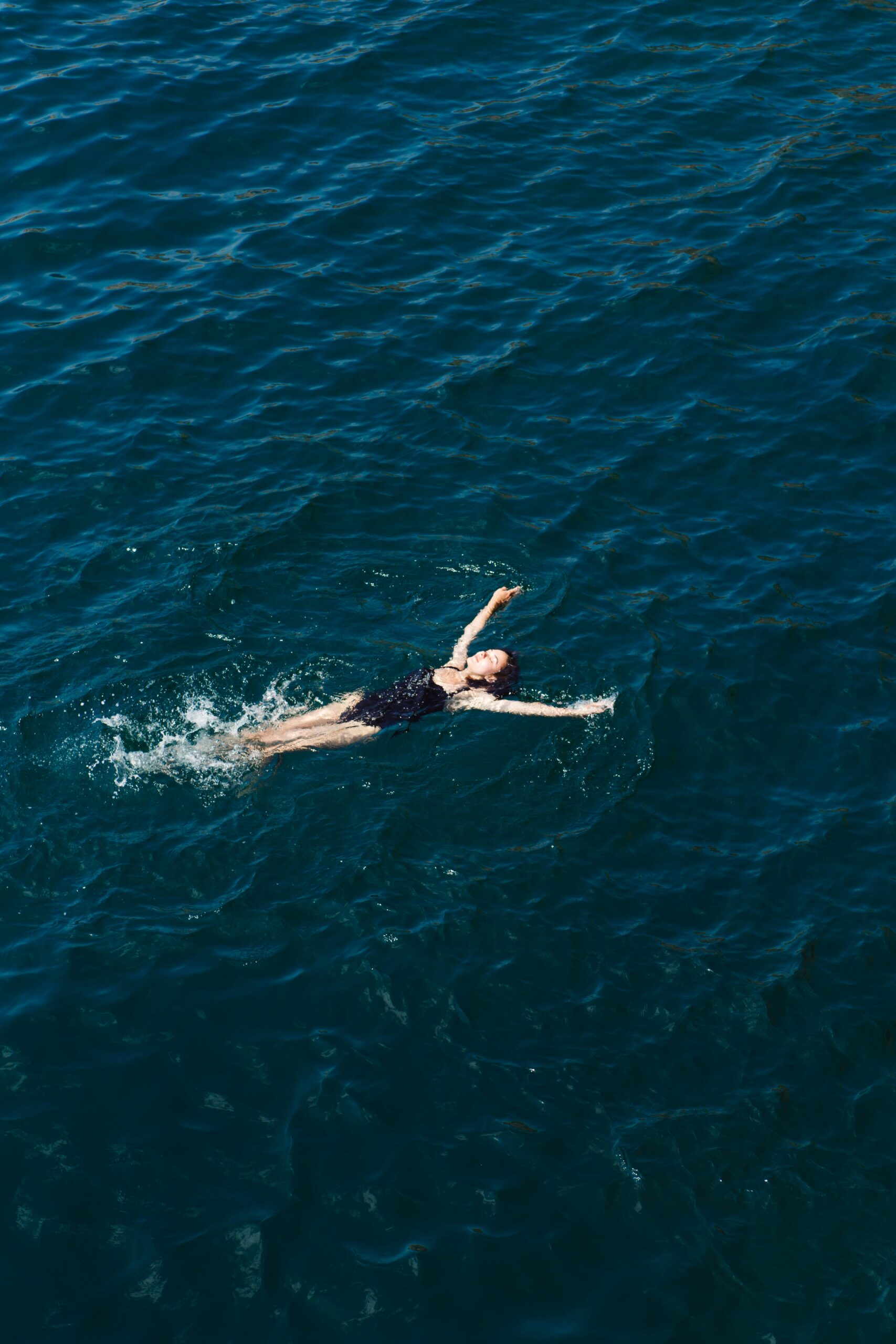

They say water heals, but can it silence decades of self-doubt? I thought swimming in London would be a bleak compromise, but through early mornings, cold water, and crowded lanes, I found an unexpected freedom—and a way to quiet my inner critic.

By Lou G

I used to be rolling in from the club at 5 AM, grabbing a couple of hours’ sleep before work. Now, I’m up at 5 AM after a solid eight-hour slumber to… swim.

Before you roll your eyes and think, Oh no, another personal essay about the transformative power of cold water and why you too should start rising with the larks, hear me out. I’m not here to sell you some wellness fantasy or preach about ice baths and green juice. I’m not here to tell you to overhaul your life. What I’ve found in the water isn’t some neat, Instagram-ready epiphany. It’s messier than that—something harder to pin down but undeniable. And it’s forced me to confront the one thing I’ve spent years trying to avoid: my body.

Let’s get some things straight. My favourite day out when I was ten? A trip to Guildford Spectrum, bombing down the water slides and fighting over inflatables with my sister. School swimming lessons? I wasn’t one to fake an illness; I liked them. I’ve always liked swimming.

But did I swim after leaving school? Not really. My relationship with water was surface-level—literally. A paddle in the ocean after a long day sunbathing? Always. A trip to the lido to escape London’s oppressive summer heat? Yes, absolutely. But calling myself a swimmer? No, not by any stretch of the imagination.

It was late May, and I was in Cornwall for a friend’s wedding on one of those rare bright weekends that almost made you forget how unpredictable English weather can be. I’d done the usual—rolled up my jeans, dipped my toes in the icy sea, and retreated quickly, wrapping myself in a jumper before sitting on the beach with a beer. One morning, my boyfriend’s snoring jolted me awake at an ungodly hour. Frustrated but unable to fall back asleep, I stared out the window. The sun was just rising, casting a golden glow over the beach. The rock pools shimmered in the early light, the kind of quiet, untouched beauty that demands your attention.

A group of women, all ages and shapes, were navigating the pools in their dry robes and Uggs, carrying flasks and chatting quietly. I brewed a coffee and watched as one by one, they shed their layers and leapt into a natural plunge pool, the water catching the sunlight in a way that felt almost otherworldly. By the time my coffee was done, they’d gone, leaving only ripples.

Inspired, the next morning, I did something completely out of character. I set my alarm for 4:50 AM, pulled on a tracksuit, and headed down to the same spot. Normally, I’d have sighed, said something like, “Oh, that’s nice for them,” and left it at that. But for some reason, I knew I needed to do this.

Just as the sun began to rise, I peeled off my layers and stepped into the crystal-clear water. The cold hit me like a slap, sharp and unforgiving, but instead of retreating, I leaned into it. My breath caught in my chest, then steadied as my body adjusted. It was as if my senses woke up before my thoughts could catch up—a moment of pure, involuntary clarity.

By the time I climbed out, dripping and exhilarated, I felt alive in a way I hadn’t in years. That solitary swim shifted something in me. My boyfriend had offered to come along, but I’d waved him off with a gentle “No, thanks.” This wasn’t about company; it was something I needed to do alone. I wouldn’t call myself spiritual, but in that moment, I felt deeply connected—maybe to myself, maybe to the quiet, ancient rhythm of the world around me.

Why had I not done this sooner? Was this destined to be a one-off—a fleeting “That’s a holiday thing” experience—or could I bring this feeling back to London?

I could easily blame geography or weather. I could say that I’ve denied myself this simple pleasure because I live in the UK, where it’s bloody freezing for most of the year, or point out that stumbling upon a rock pool in inner-city London is not just laughably impractical—it’s impossible. Both are valid excuses, but they’re just that—excuses.

The truth is harder to admit. It’s not about the climate or the lack of natural swimming spots. It’s my body. Or, more accurately, how I feel about my body. That’s the real reason I’ve held back. It’s not something I want to admit—not even to myself—but there it is. It’s not the water that intimidates me. It’s the idea of standing there, exposed, my insecurities laid bare for all to see. It’s the years of internalised critique, the relentless tug-of-war between wanting to dive in and fearing how I’ll look doing it.

exhilarated

This makes me sad because, in hindsight, I realise how much joy I’ve denied myself. Swimming was never just about fitness or leisure; it was a kind of freedom I didn’t allow myself to have. I spent years letting my self-consciousness win, and in doing so, I held myself back from something that now feels transformative.

I’ve always envied women who could walk around in bikinis with the kind of nonchalance that borders on heroic. Those women who strip off without hesitation, their confidence an armour I’ve never possessed. For me, there’s always been a ritual of awkwardness: the too-tight towel, the quick glances around, the little adjustments that scream, Don’t look at me too closely.

Has self-consciousness held me back from experiencing joy? Probably. Has it held me back in other areas of life? Almost certainly. But could I change this? That’s where the quest began.

There’s something profoundly humbling about water. It doesn’t care what you look like. It doesn’t judge whether your stomach is flat or your thighs jiggle. It simply exists—steady, indifferent, holding you up, carrying you forward, and sometimes reminding you, in no uncertain terms, of its immense power. In the water, you’re not defined by how you appear but by how you move, how you feel, and how fully present you are in that fleeting moment of weightlessness.

That was my first lesson: water doesn’t discriminate. The sea doesn’t care if your legs aren’t perfectly shaved, and the pool won’t eject you for having cellulite. It’s not Instagram; there’s no curation, no filters. The only critic is the one in your head, and, if you let it, the water has a way of silencing that voice.

This is not to say that I had an instant transformation. That first swim in Cornwall was magical, yes, but it didn’t erase decades of self-consciousness. I had spent years tethered to the idea that my body was something to apologise for, something to manage. That kind of thinking doesn’t dissolve with a single sunrise swim—it’s unpicked over time, like an old knot slowly coming undone. And the truth is, swimming became my unpicking.

Swimming has long been recognised as a powerful tool for improving mental health. According to Swim England’s Health and Wellbeing Benefits of Swimming report, 1.4 million adults in Britain say swimming has significantly reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression, with nearly half a million reducing their visits to medical professionals for mental health concerns as a result. The repetitive nature of swimming strokes creates a meditative rhythm, calming the mind and promoting relaxation. In a city like London, where overstimulation feels relentless, that kind of quiet consistency can feel almost revolutionary.

But let me not romanticise it too much. Swimming in London is an exercise in perseverance. I returned from Cornwall on a high, determined to keep the habit alive, only to be greeted with the realities of urban life. There are no tranquil rock pools here, no sparkling seas to wade into. Instead, there are leisure centres and lidos, both of which come with their own unique set of challenges.

I joined a leisure centre first, mostly out of convenience. It was close, affordable, and open early enough to fit around my work schedule. But it was also bleak. At 6am, the pool was already teeming with activity—triathletes zipping through the fast lane like torpedoes, older men dominating the slow lane with their leisurely backstrokes, and me, stuck somewhere in between, trying not to crash into anyone. The chlorine was another issue. Within weeks, my hair had become dry and brittle, shedding at an alarming rate. I spent countless evenings Googling “best swim caps for hair protection” and “how to reverse chlorine damage.” Spoiler: there’s no miracle cure.

Desperate for a change, I signed up for a membership at my local lido. At first, it felt like I’d struck gold. There’s something undeniably beautiful about swimming outdoors—the cold air, the sharper cold of the water, the way the sunlight dances across the surface. Those early morning swims in June felt otherworldly. I’d nod at the other swimmers, a fleeting but sincere acknowledgement of our shared madness for being there at such an hour. But by 8am, the lido would transform. Crowds of families arrived, inflatable flamingos and unicorns in tow, turning the lanes into chaos. What had felt serene became claustrophobic.

Despite the frustrations, I persisted, and slowly, something shifted. I began to care less about the things that had always felt so important. I stopped fussing over whether my swimming costume clung too tightly or whether my stomach was sticking out. It was as though the water itself had worn me down—not in defeat, but in release. There’s a psychological concept called “habituation,” where repeated exposure to a stimulus diminishes your emotional reaction to it. I didn’t realise it at the time, but swimming was my form of self-imposed habituation therapy. Day after day, I exposed myself—literally—to my fears, until they no longer had power over me.

Body Image

For context, research has shown that regular swimming can foster a more positive body image. A 2019 scoping review by Sabiston et al., published in Psychology of Sport and Exercise, highlighted that participation in physical activities, including swimming, is associated with a more positive body image. Activities that emphasise functionality over appearance—like swimming—help shift the focus to what the body can do rather than how it looks, fostering greater body satisfaction. There’s something about the act of moving through water, of feeling its resistance and buoyancy, that naturally encourages a kinder perspective on the body.

Still, it wasn’t always easy. On days when my self-doubt flared up, I’d find myself lingering at the pool’s edge, adjusting my goggles unnecessarily, delaying the moment when I’d have to walk across the tiles in full view of everyone. But then I’d remind myself: no one cares. Truly. How many times have you seen someone at a pool or on a beach and thought, Wow, they look awful? Probably never. People are far too busy worrying about themselves to notice anyone else. That realisation—that most people are as self-absorbed as I am—was freeing.

I swim alone most of the time. Not because I’m antisocial, but because I treasure the solitude. My mornings are usually the only moments not yet consumed by conversations, emails, meetings, or the constant pull of other people’s needs. When I slip into the pool, it’s a chance to set the tone for the day ahead, free from noise and demands. That’s not to say I don’t appreciate the presence of others—the older women at the lido who exchange knowing smiles with me as we brace for the cold, the triathletes who always seem to finish a lap just as I’m catching my breath. There’s a quiet camaraderie in those small interactions, a reminder that we’re all here for our own reasons.

On occasion, though, I do make connections. One morning at the lido, a woman named Shari struck up a conversation. She was in her forties, a regular swimmer who’d taken up the habit after a divorce. “Swimming is the one thing that’s entirely mine,” she told me. “No one can take it from me.” Another time, I met an older woman, Sarah, who swims at Hampstead Heath nearly every day, no matter the weather. She told me she’d started as part of her rehabilitation after a hip replacement, but now she couldn’t imagine life without it. These brief encounters aren’t friendships in the traditional sense, but they’re meaningful in their own way—a reminder that the water connects us, even if we swim alone.

There’s a misconception that sisterhood in swimming has to mean joining groups or forming communities (and there are some truly brilliant ones out there that I’d encourage you to explore if that’s your thing). But for me, it’s quieter than that. It’s a nod at the end of a lane, a shared glance of mutual understanding, the comfort of knowing there are others nearby without the obligation to engage.

It’s not about protection from physical danger but a gentle antidote to the isolation of modern life. In the water, we’re all just swimmers—equal, unguarded, and free.

But for all the poetic waxing, swimming is, at its core, a practical endeavour. It takes effort. It requires braving cold mornings, navigating crowded lanes, and, on some days, pushing through a complete lack of motivation. And yet, it’s this very effort that makes it so rewarding. The water doesn’t care if you’re having a bad day or if your stroke isn’t perfect. It meets you where you are, offering the same buoyancy to everyone, whether you’re a seasoned triathlete or a tentative beginner.

Swimming, I’ve found, isn’t about chasing some grand reinvention or aspiring to an unattainable ideal. It’s not a performance or an exercise in curating a new, picture-perfect identity. It’s about acceptance—of your body, of your limits, of the messy realities of life in a chaotic city. It’s not about becoming someone else but rediscovering who you already are. And in that quiet recognition, there’s a profound kind of freedom.

Let’s keep the conversation going over on socials: @glorioussport

Imagery posed by models via Unsplash.