The Velo Challenge

“Won’t you get bored riding in circles?” Writer Amy Sedghi chronicles the joy and hardships of a charity challenge that sees riders cycle 500km in one go around Herne Hill Velodrome!

By Amy Sedghi

Sometimes the simpler and more straightforward an idea on paper, the harder it is in reality. That’s how I would begin to try and sum up cycling 500km in one go on an outdoor velodrome overnight. The how and why, we’ll come to later, but for now believe me when I say, it’s an experience you’ll want to do once and once only. Dreamt up in 2020 by Boru McCullagh, former Herne Hill Velodrome (HHV) head coach, and Tim McInnes, Chair of the Herne Hill Velodrome Trust, the challenge puts a twist on the popular Rapha Festive 500 – an annual challenge that sees thousands of cyclists around the globe ride 500km between Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve. The aim for Boru and Tim’s remix? Up the ante, dig a little deeper and in doing so, raise money for charity. After all, cyclists do have a propensity to make rides harder and tougher than they need to be.

Since the pair completed their self-confessed “bonkers” challenge, others have rushed forth to try it out for themselves and in response, HHV have allowed ten riders each year to attempt the challenge, with successful applicants raising funds for the velodrome’s charity, Friends of Herne Hill Velodrome (FHHV) and a charity of the rider’s choice (mine was Dementia UK . At the time of writing, the ten riders who took part this year had raised more than £17,000 for a mix of charities. Even though all ten of us – seven men and three women – cycled our way to 500km on that same track, each of our experiences, highs and lows were different. That’s the beauty of an endurance event. If you want to know what it felt like to ride for almost 22 hours, here’s a glimpse into my experience – no chamois cream needed.

27th December:

3pm – 0km

When I tell people what I’m about to do, I’m asked why. The simplest answer? Well, why not! If I put my name in the hat and it’s chosen then I have to do it. Sure, it would be hard, but the sense of achievement would be huge. Taking it on also means I’d have a multitude of opportunities: to raise funds for a charity close to my heart, give myself an activity to get my teeth stuck into and delight in the spirit of those who gather around to support us.

Having completed the London Marathon earlier this year, I was overwhelmed and buoyed by the encouragement from friends, family and strangers and moved by their belief in the causes I’d chosen to raise money for – in honesty, I was hungry for another slice of that. Riding 500km (around 310 miles) or approximately 1,112 laps of the velodrome seemed like the next, shall we say, logical, conclusion. For context, that’s around the distance of cycling from London to Newcastle (and a tad more).

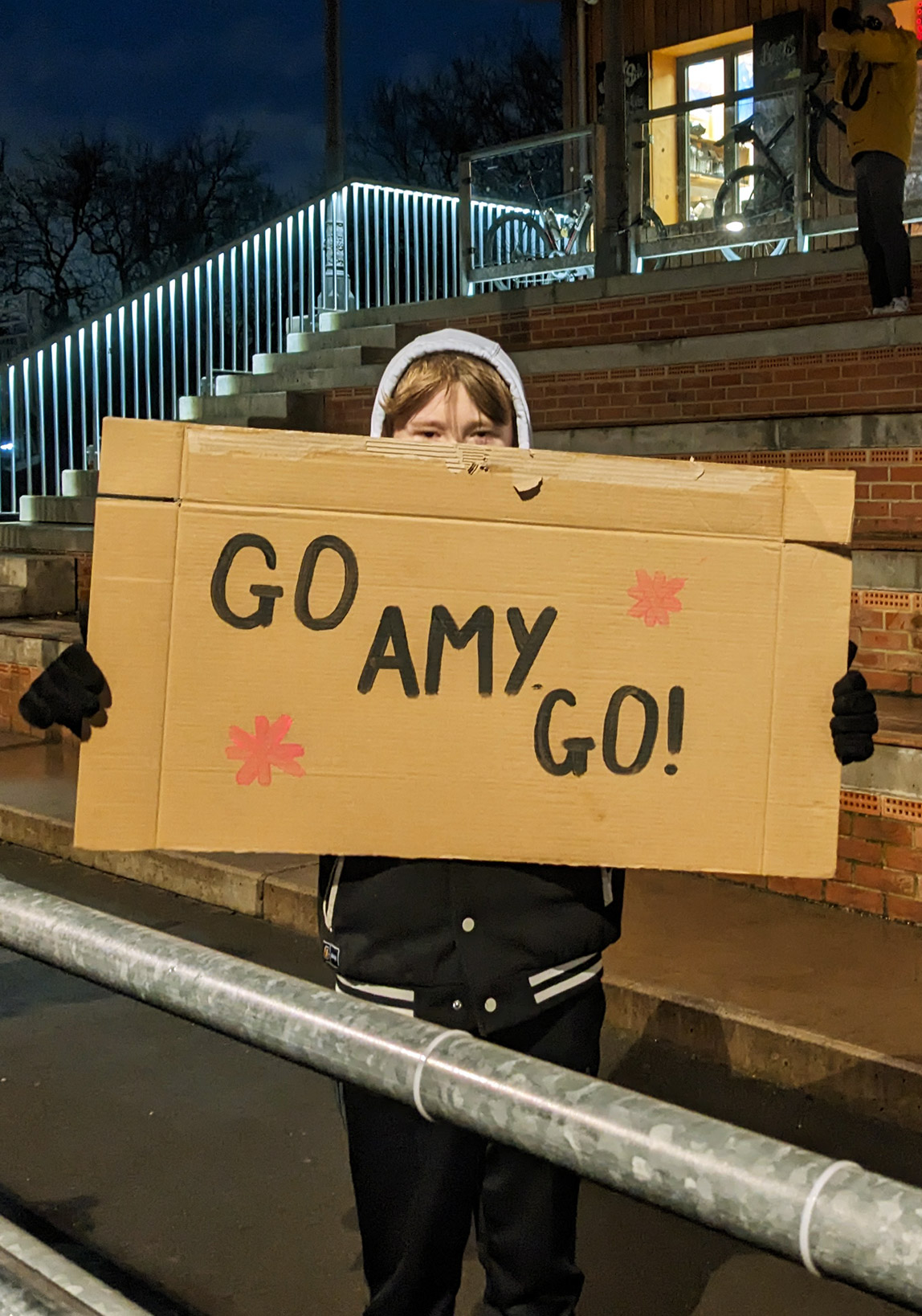

As hoped for, the first few hours passed with a flurry of faces – well known and new – coming down to cheer us on. Banners flapping in the wind, cowbells rung with enthusiasm and faces grinning from under dripping rain jacket hoods, it all helped to spur you on.

5pm – 50km

“I think the first mistake I made was treating this as though it was like a regular ride,” admits Jess Golding, one of my fellow F500 riders, who raised just shy of £1.5k for Crisis UK. Her longest ride previous to this was 360km – an extra 140km didn’t feel like too much of a jump, she says, but she soon realised that this was a very different beast. “It’s just not comparable to any other kind of ride… I think I was wildly unprepared for how challenging and difficult this was going to be.”

control

Sure, there are no hills to climb or tricky landscapes to navigate, but cycling continuously round and round on the flat brings other trials. “A lack of variation in terrain means your knees are pretty much always engaged. There’s no traffic to give you a quick breather. Those little things that break up a typically long ride, along with the constant spinning, is what really wears a rider down,” says Rachel Chung, an overnight volunteer who completed the challenge herself last year. Remembering the effect that motivational cheers and early morning chats had on her, especially during the ‘graveyard shift’ (2-6am), she was keen to give back at this year’s event.

8pm – 100km

There’s a famous saying popular among athletes: “Control the controllables”. The idea is that there’s a number of things within your control, but those that aren’t… well, don’t waste your time and energy on them. I had this in mind for the many hours during which 25kph winds made half of the track soul-destroying to cycle – I thought the headwinds in the Outer Hebrides had been bad, but this was constant. When I started yelling to my poor friend Sian, who was keeping me company throughout the night (and acting as a helper during the challenge), how intensely I hated the wind – as if it was a person with a vendetta against me – she gently suggested it might be time for a break and a cup of tea.

Jess and I both quickly found that sticking unwaveringly to a plan for breaks just wasn’t going to cut it – we’d both hoped to allow ourselves breaks every 50km but we found ourselves stopping earlier. There’s a fine line between pushing yourself just a bit further and not listening to your body. It may feel like failure when things don’t go to plan but that flexibility is crucial, especially when conditions are out of your control. As positive as I tried to be about the weather (it wasn’t snowing, icy or torrential rain, right?), I had to admit, the weather was consistently grim and that grinds you down. “Remember, it’s a marathon,” my boyfriend, James, tells me as I fork pasta into my mouth.

28th December

1am – 170km

As well as the mental and physical fatigue, along with most of the riders, I battled with nausea. So much so, that I would place it as the number one challenge of the ride, up above the howling wind, rain and feeling saddle sore. After all, the key piece of advice we were given was to keep eating. How to do that while feeling like you’re constantly going to throw up… now that’s a puzzle. Turns out, you can very rapidly reach your limit of banana consumption, but luckily I’d prepped with a wide mix of snacks and food, from boxes of pasta, packets of brioche, pots of rice pudding, bags of my favourite sweets, crisps, electrolytes and gels. It’s after 1am when I give in to a 20-minute lie down. I have to remind myself that it’s allowed – later on when I see my total stoppage time of nine hours over the event, I feel foolish for even debating the rest.

3:28am – 210km

If you’d asked me beforehand if I was mentally prepared, I would have said yes. I still think my stubborn mentality is stronger than my physical strength but of course, we all have dips. “It’s a rollercoaster,” says Sebastien Lawson, an overnight volunteer who took part in the challenge last year. As he frothed the milk for my umpteenth coffee in the early hours, he reassured me that it is part of the journey to feel fine one moment and then be struggling the next: I just needed to ride the wave. Looking around at the tired faces, the lost expressions of those sitting on plastic chairs supping pot noodles and glancing out at those riders still doggedly turning the pedals out on the wet track, I realised we were all grappling with our own Everest, and in fact, there was something reassuring in accepting that. Like many things in life, it’s helpful when you realise you’re not alone in your feelings.

6:17am – 250km

Earlier on, Sian turned to me as we were riding round the track together and said: “The first inkling I got of what it was like for you was when I was riding at 4am, 15 minutes passed and I looked at my watch to see it was 4:05am.” People always ask about the tedium. “Won’t you get bored riding in circles?” but that aspect of it I was quite confident about. This was something I could control. I had music, podcasts and people to have conversations with. I could watch the famed – and very cheeky – velodrome fox popping up throughout the night and I actually enjoy getting lost in my thoughts. What I couldn’t do much about was the tiredness: inevitably at some point during the 24-hour ride, my body and brain would hit exhaustion point.

Sleep deprivation is something I knew I wouldn’t deal particularly well with. As Charlie – another of the riders who would go on to finish first – had put it about whether to sleep or not: plan a) was no, plan b) was yes. By 6am I was firmly on plan b and stumbled up to my yoga mat bed, falling asleep with my helmet still on. Upon waking, I was worried I’d missed a beautiful sunrise but nope, it was still grey… just a lighter shade.

4:47pm – 400km

In our application, we were asked what would motivate us to get through riding 500km overnight. My answer? Carbs, sweet treats and smiley faces. When it comes to describing how pivotal the support of those showing up, sending encouraging messages and donating to the fundraising pages is, it’s hard to do it justice. When I was at my lowest ebb, James and Sian listened to me tell them a hundred times I couldn’t do it, but with their kindness and generosity, I managed to keep going. Although you ultimately have to believe in yourself, that of others does have a huge impact when you need a helping hand. As Jess commented: “Don’t be a hero, let people help. It doesn’t undermine the achievement.”

9.12pm – 484km

I was hoping a secret rocket would light beneath me when I saw the last 10 miles (16km) and I’d finish in an Olympic-worthy sprint that would result in fireworks and cheers. In reality – like when I had the last few miles on the London Marathon earlier this year to complete – it felt like the hardest and longest distance that I would be unable to make a dent in. I wondered if my GPS bike computer had stopped working or maybe the track had grown. Sian rang the last lap bell and I cycled over the finish line with intense relief, literally falling off my bike when I stopped, showering champagne everywhere. Festive 500? Done.

If you’d like to donate to Amy’s fundraising page, where funds will be split between the Friends of Herne Hill Velodrome and Dementia UK, you can do so at this link.

In numbers:

- Outfit changes (bibs, base layers, jerseys and jackets) – three (some didn’t change, but for me this was a lifeline as with every fresh set of kit, I felt human again)

- Changes of socks – two

- Hot drinks – 6x coffee, 2x bidons of tea, 1x flask of tea, 1x hot chocolate

- Food highlights: – 4x rice pudding with jam, a flask of custard and one giant almond croissant brought to the track by a friend

- Naps – two (one lie down for 20 mins and another for around 45 mins)

- Hardest kms – 354-370km

- My most desired item during the ride – a cuddle with a cat (both warm and comforting)

Editorial Design by this is root

Title Image by Josh Gordon