Female Bikesmiths

A history of bike builders: past, present and future. We speak to the women breaking the mould by welding bespoke frames

By Emily Chappell

Almost forty years ago, a young engineering student called Georgena Terry was teaching herself to weld in her basement in Rochester, New York. “There was this pile in the corner of rejected tubesets and forks all different lengths,” she recalls brightly. “It was one mistake after another, until I learned.”

She explained that in those days, bicycles were always built with a horizontal top tube, no matter what sacrifices this might necessitate elsewhere in the frame. For a smaller build, these were considerable. A bicycle frame is composed of nine tubes – in Georgena’s case, made from steel – and a frame builder will cut these to different lengths, and join them at different angles, to account for a rider’s size, proportions, flexibility and riding style.

These days you can buy a mass-produced women’s bike, which will usually have a shorter top tube to accommodate the fact that, on average, women are claimed to have shorter arms proportional to their legs than men do. In order to provide the same riding experience, every other measurement on the frame has to be reconsidered, so that the overall fit of the bicycle feels right.

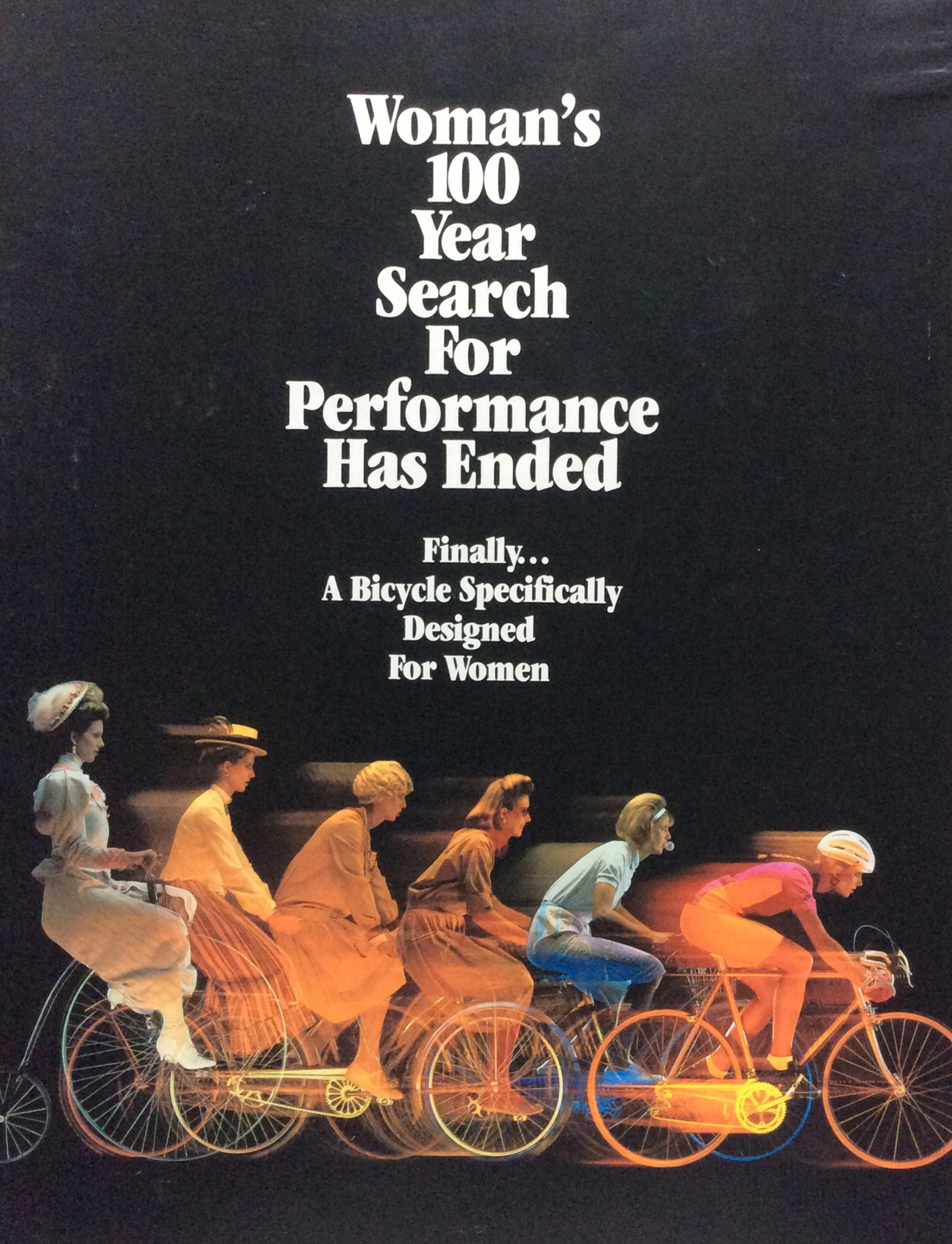

“If you can figure out why people can’t build small bikes properly, then you understand frame geometry,” Georgena smirks. One of her initial strokes of genius was to incorporate a smaller front wheel which, she is hasty to emphasise, was not her own idea, and originally appeared on track bikes in the late 1800s. Building a frame around a smaller front wheel solved a couple of the design problems presented when building bikes for smaller people. Within a few short years, a one-woman frame building operation in a basement rapidly evolved into Terry Precision Bicycles, a company that, as well as pioneering women specific geometry, popularised the cut-out saddle, arguably the most significant innovation in women’s cycling technology.

Georgena’s creation caught the eye of other riders when she rode with her cycling club. Many of them had also struggled to find a bike that fit them properly, and requested that she build one for them too. “At first I was doing bikes for men and women, and then I thought – you know, men have plenty of stuff to choose from. I’m just going to focus on women.” She exhibited her creations at rallies and trade shows around the country, and soon had more orders than she could fulfil on her own. Outsourcing the building to Japan meant the bikes could be sold at a much lower price point, making them accessible to even more people. By the early 1990s, thousands of women were riding Terry bicycles. Without entirely meaning to, Georgena had identified a yawning gap in the market, and offered a convincing solution to fill it. Not only did this lead to the success of her own business – it was also the first wake-up call to an industry that had barely even begun to consider that people might need different bicycles, depending on their different shapes and sizes.

While Georgena Terry was taking the trade shows by storm, an English teenager called Isla Rowntree was negotiating with her school to be able to study design (considered a boy’s subject). She was working in a bike shop and spending much of her spare time exploring the West Midlands with her local cycling club.

INNOVATION

Isla went on to ride professionally, winning the National Cyclocross Championships three times, but as well as her strong legs, her success relied heavily on her mechanical ingenuity. As a woman of diminutive proportions, she had found – like Georgena – that commercially available bikes didn’t fit her, and so set about making her own improvements.

“I think I bring my lived experience of my physical size to bicycle design and frame building,” she told me. “In terms of frame design and fit, but probably more in terms of component design and fit.” She continued: “I consider myself to be a confident and competent cyclist in terms of bike handling,” she said, “but that is altered dramatically when I’m riding a bike with brakes that I can’t reach. If you extrapolate that to somebody who’s new and is terrified of falling off, it becomes a barrier to entry.”

INGENUITY

Isla’s knowledge and expertise meant that she was the natural person to turn to when her friends started looking for starter bikes for their children. But Isla found there was nothing she could recommend – at that point, children’s bikes were cheaply made, scaled-down versions of adult bikes, with proportions that didn’t suit children’s anatomy, and weighed almost as much as the children themselves. Concerned that these monstrosities would put children off cycling altogether, she applied her design skills and cycling expertise to the problem. The result was Islabikes, a company that has single handedly reinvented the children’s bike market, selling lightweight, high-quality bikes, designed to instil a lifelong love of cycling.

“With a young child, you’re at the limits of what’s mechanically possible. Tiny developing hands have to stop their own body weight. I made smaller diameter handlebars, thinner grips, adjusted the lever shape itself and the weight of the springs. You add up all the tiny little bits, which individually you think wouldn’t make any difference, and the collective difference is significant for the person you’re designing for.”

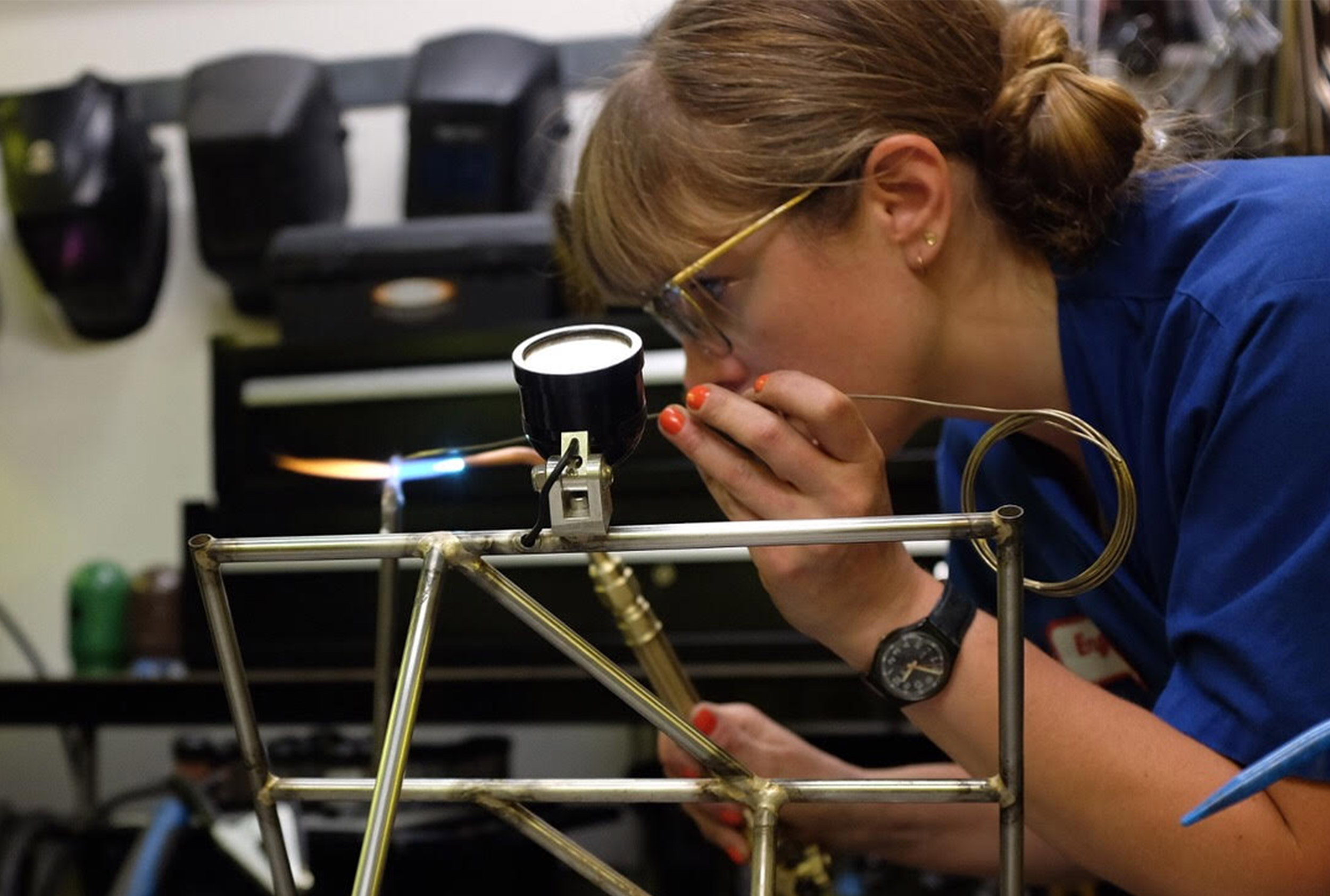

A couple of years after Islabikes was founded in 2006, the world plunged into one of the worst recessions in history, and a young sculptor called Caren Hartley found she was no longer able to find funding for the public art projects she’d been working on. So she sidestepped into bikebuilding and immediately took the place by storm. As an artist and jewellery designer, with only a recreational interest in cycling before she made it her career, Caren’s route into framebuilding was less predictable than those of Isla, who was steeped in bike shops from an early age, and Georgena, who worked as an engineer before setting up Terry Bicycles. But far from being a weakness, her background is what makes her stand out.

Almost overnight, Hartley Cycles became the talk of the town. Caren fulfilled her dream of exhibiting at London’s Design Museum, and won several prizes at Bespoked: the UK’s handmade bicycle show. Her bikes are ‘objets d’art,’ combining technical skill with a jeweller’s eye for detail, and finishes that vary from stainless steel to gold leaf. Some say they’re too pretty to ride, but that hasn’t stopped her doing a roaring trade out of her south London workshop.

And her bikes have been ridden all over the world, in races, on long-distance tours, around cities, and over mountains. Having had a long academic interest in how people engage with objects, Caren has revelled in putting this to more practical effect, and considering how to design a usable object around the fluctuations and inconsistencies of the human body. “Because it’s custom geometry, yes,” she explains, “but people change. [I ask myself] what kind of riding are they going to do? If they wanted to go for really long rides, I’d think about easing pressure on particular parts of their body, and how I might do that – would it be with tyres? Or position? Or the handlebars they’re using? Maybe it’s about how I build flexibility into the frame, so that it’s comfortable. I think in a much more practical sense now.”

PRACTICAL

Just as Isla Rowntree’s struggles with mainstream bikes and components led her to design new ones, some of Caren’s innovation stems from her initial outsider status – she had considerable metalworking experience, but knew very little about bikes beyond how to ride them. “It’s been an advantage for me,” she says, “that I don’t necessarily think about the correct way of doing things, because I don’t necessarily know the correct way.”

In an industry that is often held back by its slavish adherence to tradition, Caren’s approach extends beyond the workshop, and has been brought to bear on the way her bikes are sold and marketed. In 2017 she joined forces with fellow framebuilder Matt McDonough to create Isen Workshop, a bike brand that sits somewhere between the big companies that churn out thousands of identical bikes, and the traditional solo framebuilder who welds tubes in a leaky shed.

Isen has overhauled and streamlined the process of acquiring a custom bicycle. Every single part of the build, from design to painting, is done in-house, but rather than designing each bike from scratch, Caren and Matt offer several different prototypes that can be customised and upgraded in a mind-boggling number of ways, to suit each customer’s anatomy, riding style and budget. The duo are experimenting with 3D-printing components, which enables them to create unique parts in-house without a large production run, and have begun working with titanium, which enables them to improve comfort and save weight – and it looks great.

UNIQUE

I realise what a step forward this is when I speak to Adeline O’Moreau, an exuberant Belgian cyclocross racer, whose company Mercredi Bikes seems to be more or less an extension of her personality. Her cartoon hued bikes are far more at home when streaking around a muddy ‘cross course than posing in a showroom. “People who get a custom bike don’t really do it for the bike itself,” she tells me, “they do for the journey, and the relationship that they build with the builder. You have to give a lot of yourself; your attention, your time.” Adeline, I sense, prefers building a bike to running a business, and she’s happiest when thinking her way through a design problem, rather than putting together a frame that looks very much like the last one.

This constant innovative itch is something shared by the other framesmiths I spoke to, though they have all expressed it in different ways. Caren is attempting to refine the unwieldy and long process of tailor-making a bike to a person’s individual requirements; Isla and Georgena have each, in their own way, changed the face of the bicycle industry.

Most bike brands now offer the cut-out saddles and women specific geometries pioneered by Georgena Terry. I and many of my friends ride further, faster, more often and more comfortably as a result. A couple of years ago, just about every kid in my local park was riding one of Isla’s designs. Now there are even more young cyclists around, but only about half of them are on Islabikes – a sure sign that the rest of the industry is catching up. Isla doesn’t mind this – she sees leadership as part of innovation. “I hope that the cycling industry can learn from our experience, or any industry for that matter.”

PERFORMANCE

After carving out new niches for children’s bikes, Islabikes have set their sights on another underrepresented market. Their Icons range, launched in 2019, is designed to meet the challenges faced by older cyclists. Georgena eventually sold the majority of her business and has gone back to designing custom frames for individuals. Of course, we know that the best innovators are always looking ahead, thinking about what’s next around the corner.

Editorial Design Root