Pioneer Of The Deep

Californian daredevil Dottie Frazier’s love of scuba diving meant that she had to break into a man’s world. We explore the life and achievements of the adventurer and heroine of the deep

By Annabel Herrick

In 1955, Dottie Frazier was the first woman to become a qualified scuba instructor. But that’s just one accolade on the long list of achievements from her 99 years on the planet. A tenacious go-getter, barely 5ft tall and weighing under 8 stone, Dottie consistently conquered a man’s world where women before her wouldn’t have dared go. Sadly, Dottie died on February 8th this year, not quite reaching her 100th birthday, but this remarkable woman broke barriers and displayed a fierce independence and go-getting attitude that stayed with her throughout her life.

Growing up in California, Dottie felt an affinity with the sea from a young age – she was swimming at the age of three, sailing competitively aged six and a water taxi driver aged nine. It’s not just what Dottie did but when she did it. In the 1920s, she was boating, surfing and ‘skin diving’ (otherwise known as ‘free diving’) before these activities had become recognised pastimes. The sea represented her work and life; her entrepreneurial spirit saw the ocean’s bounty as an opportunity to make money from a young age. She joined commercial fishing trips, searched for sunken coins and entered diving competitions. The deep blue presented endless opportunities for a young girl who couldn’t sit still, but it was also the setting for some harrowing moments in her childhood. Aged seven, Dottie saved her five year-old sister Jeanne from drowning when she fell overboard, “I dropped my pole and jumped over the bridge. I managed to keep her head above water,” she remembered. Later in her career, she even came face-to-face with a great white shark, which she fended off by swimming directly towards it, “It looked like a big submarine with a mouth. I had nightmares for a long time,” said Dottie. Needless to say, stories like this are common throughout her life, and yet her raw instinct and love for the wild waves kept pulling her back.

instinct

As someone who was never afraid to stand out, even Dottie’s childhood pet was outlandish. “I had always loved snakes and lizards. I had a six-foot Gopher snake named Buddy who would swim with me,” she explains. Seeing as so much of her life revolved around the sea, it was only natural that she would take Buddy along. “He would wrap around my neck and I would wait for a big wave. Then he would slip off and swim by my side for half a mile.” These stunts drew crowds daily, where locals would gather to watch this tiny young girl swim laps in the Pacific with a giant snake rippling at her side. Strangely enough, Dottie’s foray into watersports began in the snow. “I took to skiing like a duck takes to water. Since it was seasonal I started water skiing in the Long Beach area,” she says. However, taking it one step further than juvenile playtime, go-getter Dottie joined an acrobatic team of water-skiers that consisted of three boys and three girls who put on numerous shows. Even an injury didn’t stop her in 1964, when falling off her snow skis resulted in a spiral fracture to one leg. “I was in a cast for two years. For the last six months, my buddies would remove the brace and zip me into the wetsuit,” she says, “I did all my kicking with one leg until the injured leg was completely healed.”

Once she was back on two feet, Dottie looked for the next challenge and started learning how to springboard dive from the top deck of her father’s boat, “I could do a jackknife, swan dive, somersaults, back and front flips,” she recalls. Forever encouraging her antics, Dottie’s father put her forward for the Junior Olympics when she was 10, where she suffered yet another injury; 13 lineal fractures of her lower back. It was uncertain if she would ever walk again. And yet, she persevered and every chance she got she was skin diving, although she admits, “Even now I can’t remember going a whole day without back pain.” Shortly after, Dottie took up tennis and racquetball. “I always loved competitive sports,” she says. In school, she played soccer and water polo and was a member of the surfing and swimming teams. Dissatisfied with simply taking part, Dottie joined the Red Cross to become a certified instructor in small craft, sailing, canoeing, kayaking, water safety, lifeguarding, and first aid. Before long she began teaching classes just as skin diving was becoming popular. “I had taken a secretarial job after graduating from business college but I lasted just two months.” Dottie continues, “It was not for me to sit in an office all day.”

As she looked for other work, Dottie’s father heard of a skipper who needed help on his boat. Despite being a girl, he put her forward, believing in Dottie’s impressive experience at just 19 years old. Dottie recounts the skipper’s reaction. “When he found out my dad was suggesting a girl, he said “no,” quoting his response: “I am not running a school and it is bad luck to have a woman aboard.” After much persuasion, Dottie was interviewed by the skipper, “I wore bulky clothes to hide my boobs, a knit watch hat and no make-up – so nothing feminine. I got the job.” Dottie worked solidly for two months and endured a ferocious storm whilst at sea. “I got the bus home looking very dirty and certainly not female. I didn’t feel like one either. I just thanked God I was still alive,” she says. The voyage didn’t dampen her spirits; she considered the experience an opportunity to deepen her understanding of her aquatic world and despite the terror of the storm, she recounts this magical period of her life warmly. “I learnt which planets would guide us and how the stars change their positions as the seasons change.”

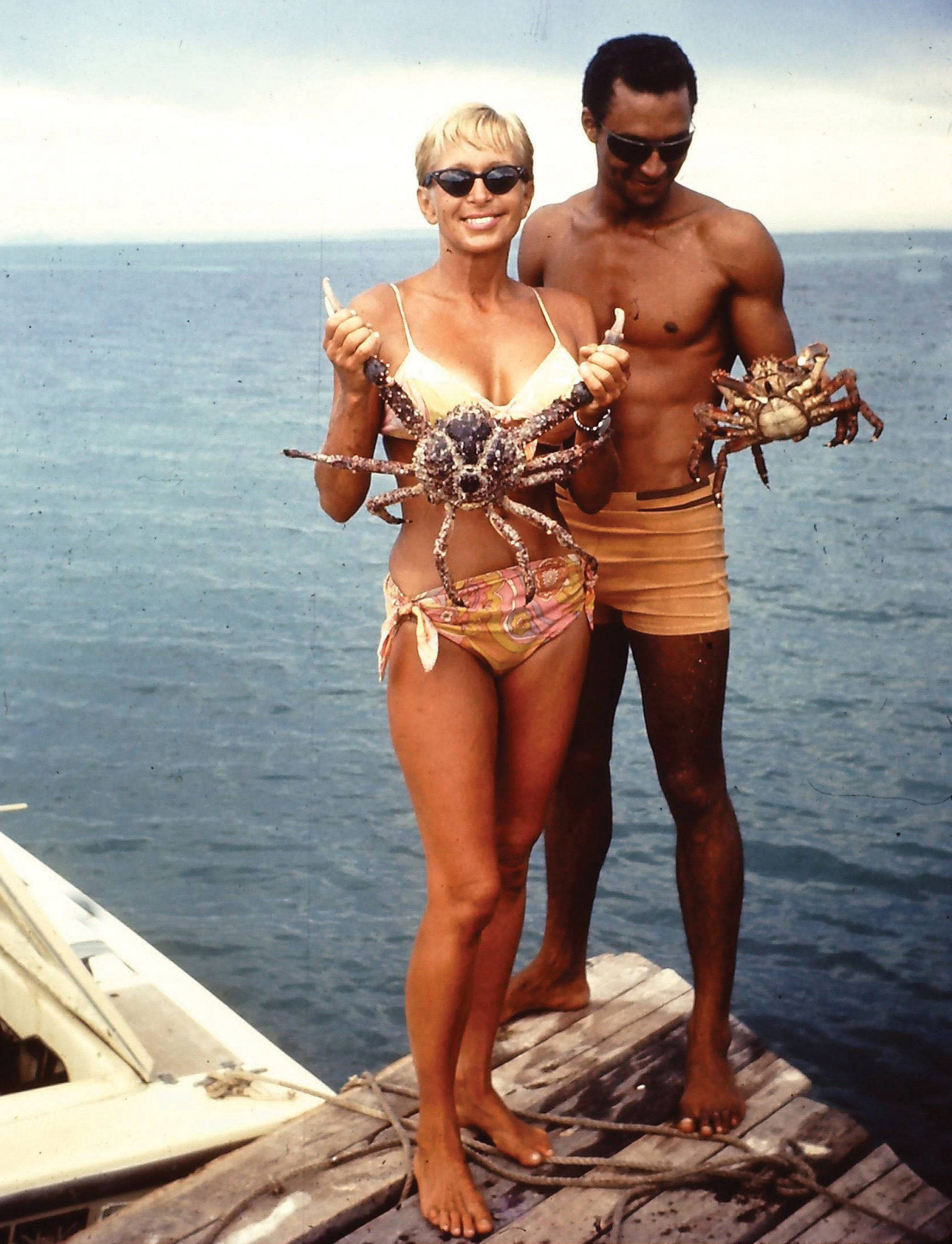

During this time, Dottie also learnt how to forage for food whilst at sea. “We would pick a cove and run into feral pigs, deer, buffalo, goats and foxes. We even hunted rattlesnakes, which we took back for supper,” she says. Her father would teach Dottie how to turn fisherman’s rags into equipment, as she remembers, “In no more than 15 minutes we’d have homemade cloth bags full of two-inch cockle clams. Dad made delicious clam chowder.”

One day with her father, a minor slip-up and an old sailor trick marked the beginning of her lifelong obsession.” Her dad dropped a coffee pot into 15ft-deep water. He convinced me I could go down and get it,” she recalls with pride. “He handed me a small anchor with a line attached to it. I fetched the coffee pot and after that day it wasn’t too long until I was diving at that depth all the time.” Next, her father worked on a piece of homemade equipment, which, little did he know, would launch Dottie’s career in scuba diving. He held a piece of fire hose up to her face and cut it to fit before attaching a piece of circular glass from a broken window. Using scraps from the boat, he had built a ‘faceplate’– also known as a diving mask. “The first time that I wore my mask was like a miracle,” says Dottie. “I could see the fish and all their vivid, beautiful colours, making the most unbelievable underwater forest.”

She explains this was a defining moment for her. “From that day on, this became my new world.”

Thrilled with her father’s latest invention, she was the envy of other children who, like Dottie, made pocket money by diving for coins. “No one had ever seen a diving mask before,” she says, gratifyingly. “We’d normally store the coins in our mouths but soon enough I had more than I could hold. I made a cloth bag, which I attached to my trunks with safety pins.” Clearly, she had inherited her father’s knack for nautical handiwork. With her new kit, Dottie was keen to show off her skills competitively and described how one of her diving friends asked if she would enter a Diving Derby as his partner. They ended up catching an electric ray, which won them first prize. However, Dottie wasn’t happy with her options as the only girl and protested to the committee, saying that the prizes were only set up for men. “Even though the men’s prizes included practical objects, such as wetsuits, spearguns, fins and masks, the women’s prizes were decorative and boring like bathing suits, beach sandals, hats and towels,” she remembers, in exasperation. “We never received equal prizes.” The committee eventually listened to her complaints and after a few years a women’s division was formed.

Dottie was used to representing the minority after spending years as the only female member of a local motorcycle club, “My affair with motorcycles began in the late 1930s. I was usually the only woman at outings,” she says. She then decided to use her diving experience to empower other women, starting a new club with friends called ‘Aqua Familias’ to encourage them to get involved.

“We always took turns to go out skin diving – the men went together then the women got their time,” she explains. The club became very popular and two years later they were too full to accept any new members.

It was Dottie’s friend Jim who helped take her diving to the next level. When Dottie was aged 32, he suggested she apply to the Underwater Instructors Certification Course. Once again, she was rejected, receiving an all too familiar response: “Los Angeles County thanked me for my interest but suggested that I would be happier taking a class at the local YMCA.” But her cheque was never returned. Feeling downtrodden, Jim insisted they turn up at the class anyway. The pair were greeted by the instructor who asked Dottie if she had received his letter. Jim spoke up, pointing out that the cheque had technically been accepted, “I guess she’s a paid member of this class. Let’s go sit down, Dottie,” he told her.

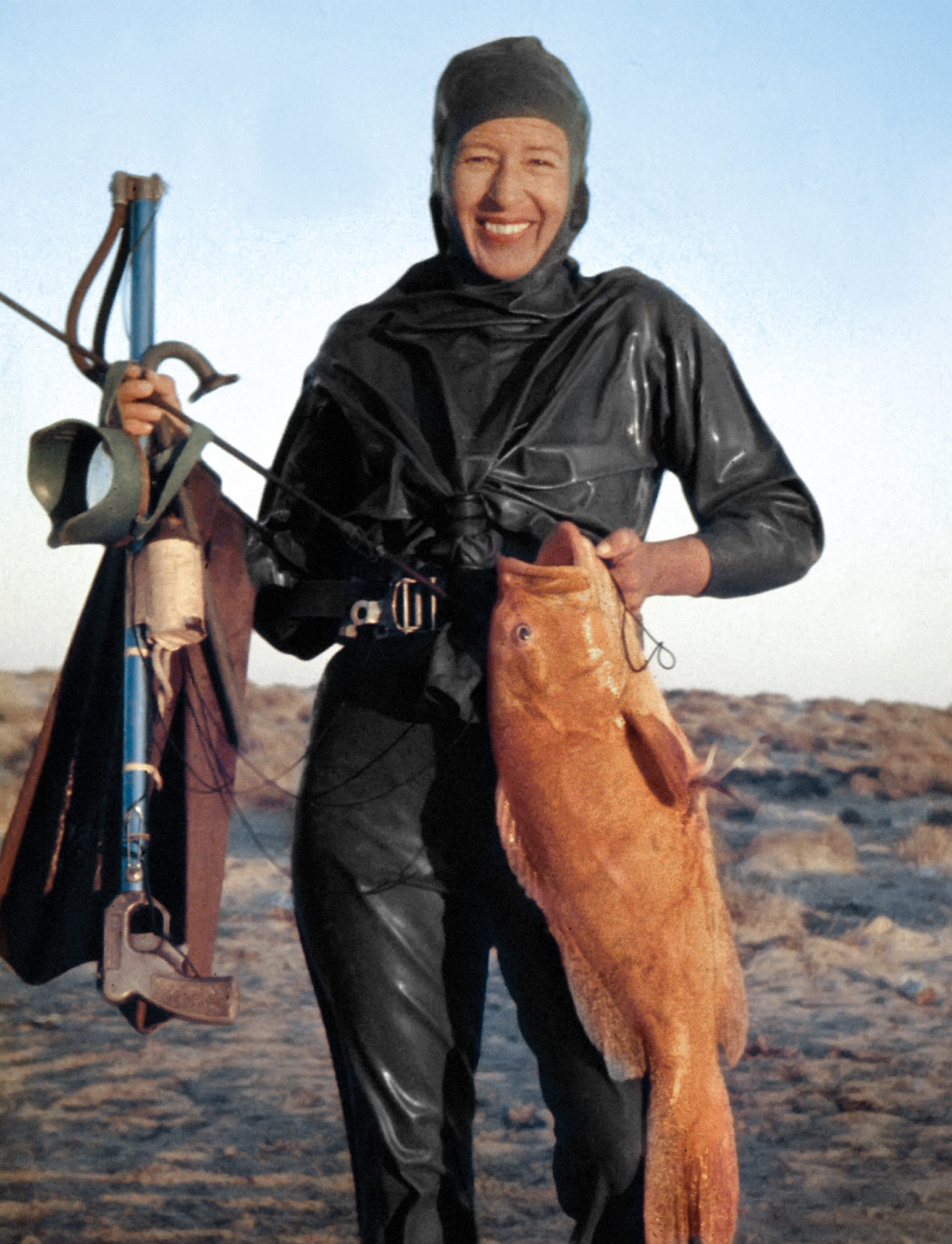

Shuffling to her seat, Dottie was unaware that she was paving the way for every female scuba instructor to come. “There was mumbling and grumbling from the other students – all men of course. I felt really uncomfortable. Jim told me to just ignore them,” she recalls. Throughout the course, Jim stood firm and supported Dottie, “I could not have bluffed my way through if it hadn’t been for Jim,” she says. At graduation, the pair received the two highest grades; Dottie for water work and Jim for written. Then they were given seats on the board of directors for the Underwater Unit.

Now Dottie was officially qualified, she highlighted her next challenge of finding somewhere to teach. “Becoming an instructor was easy compared to convincing the public to accept me.” A shop was willing to take her on as their first scuba instructor, but only for a trial period. “No one signed up to classes and I was about to give up,” said Dottie, “then the boss told me that a doctor had booked a private class of eight, all medical men.

Reflecting, she continues, “No one had mentioned that the instructor, ‘D. Frazier,’ would be a woman. Diving was strictly a man’s world, and it was almost unheard of for a woman to be a diver, let alone a scuba instructor.”

Despite her concerns, Dottie couldn’t wait. “I was so excited over the next four days that I could hardly sleep.” On the morning of the class, Dottie had given a talk dressed in a cotton dress, high heels and silk stockings. There was no time to change into something more casual before her first scuba class, so she powered on regardless, hoping her outfit wouldn’t aggravate the situation. She remembers the moment the doctor answered the door, noting his response: “Oh no, there must be a big mistake. I’m sure the others in the class would agree that we wouldn’t take lessons from a woman.” Dottie persuaded the doctor to let her stay, asking for a chance to talk to the group before they dismissed her. Desperate to convince them, she spoke confidently, “I can teach you far more than most instructors. I was raised on a boat from six years-old and I’ve taught swimming and skin diving since my teens.” The group let her teach the first half of the class. If they still weren’t happy afterwards, they would receive a refund and Dottie would find them a new instructor.

One month later, all members of the class passed – including the “extremely hard” written test that Dottie herself had compiled. Finally having pulled it off, she allowed herself to recognise the magnitude of this moment. “I was proud of my first class and my new career as the first female scuba instructor in the world.” Dottie went on to train more than 2,000 scuba divers.

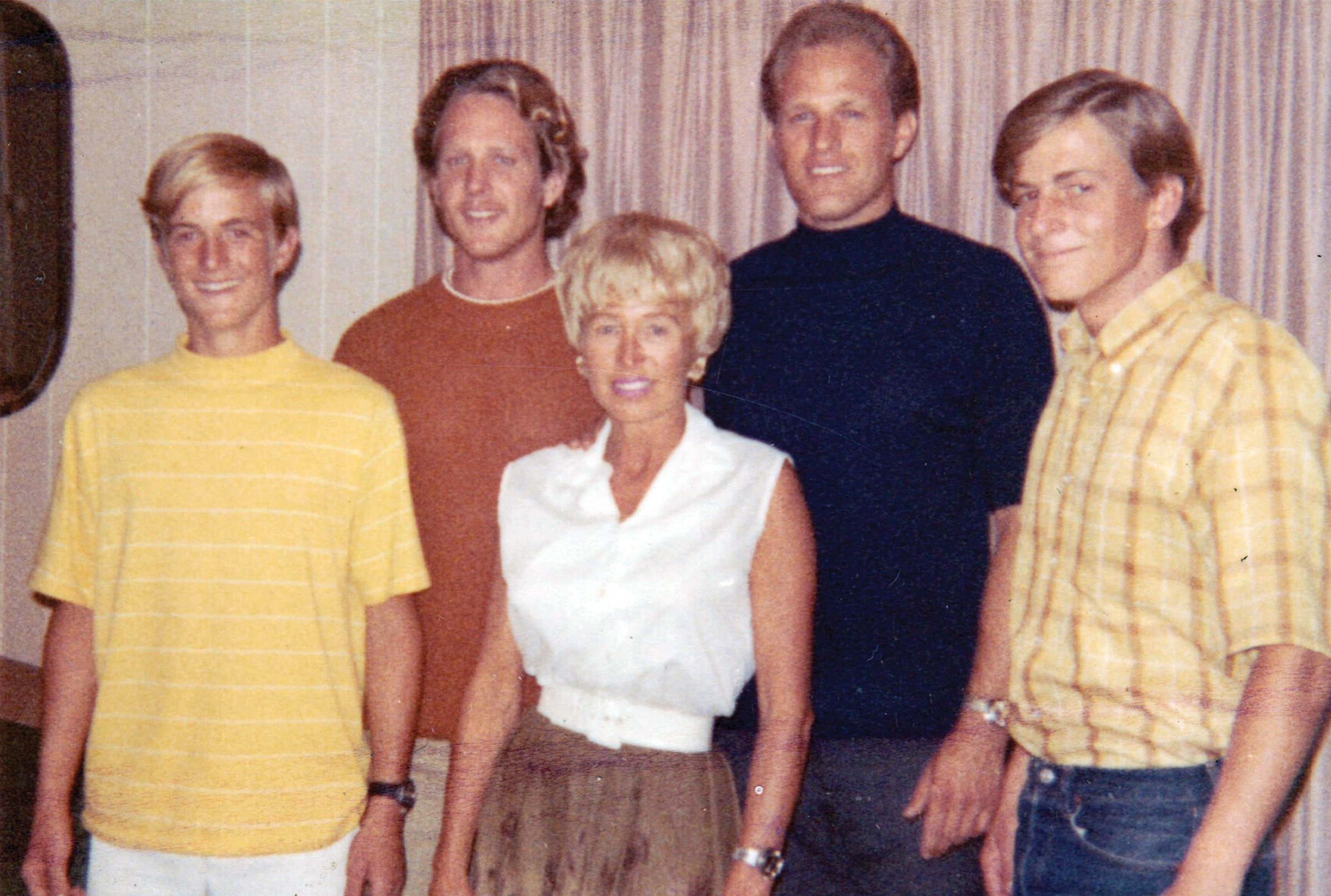

Passing down her love of diving to her four children, her 18 year-old son Darrell graduated the same scuba course and joined his mother on training days. “We were the only mother-and-son team that I had heard of,” said Dottie proudly. In her older years, she slowly retreated back on land, grounding her feet as she left the ocean for a new generation; a playground for the young. Reaching her 84th birthday, she would still ride her motorbike before winning four gold medals for billiards in the 2012 Senior Olympics, aged 90. During her last years, she concentrated on hobbies closer to home by running on her treadmill and tending to her fruitful garden full of pineapples, beetroot, plums and artichokes. She ate everything she grew, needing the energy: “There’s no age limit,” she said, “I don’t want to quit for a while.”

Iconic