Defeating All Obstacles: Amy Conroy

How does one reclaim their confidence after a life-changing event? Amy Conroy talks about traumatic teenage years to success as a basketball champion, and why one photoshoot took longer to come to terms with

By Liz Connor

Photography by James Cannon

There’s something to be said about pushing yourself out of your comfort zone. Quitting your job and moving to another country. Taking a solo trip when the thought of boarding the plane forms knots in your stomach. Leaving the safety of a relationship you know you’ve outgrown. But if we’re on the topic of feeling fear and doing it anyway, wheelchair basketball player Amy Conroy takes the crown.

At just 30, she’s a three-time GB Paralympian, a Wheelchair World Basketball Championships Silver medal holder and a European Bronze champion. But overcoming the psychological barrier of removing her prosthetic leg for a recent photoshoot with portrait photographer James Cannon proved to be one of the biggest challenges of her life so far.

“When I posted the pictures on Instagram, I threw my phone across the room,” recalls Amy. “I have a lot of confidence when I’m wearing my prosthetic leg but being seen without it has always been something I’ve been scared of.” The Paralympian and the photographer chose a public swimming pool as the location for the powerful shoot, a space where Amy had always felt self-conscious about her disability.

“I loved swimming but hated being in a swimming costume, getting into the water and people staring [at me]. I’d spent my life covering my leg with a towel,” she says. The photographs were a way for her to reclaim her confidence out of the water. “Up until the shoot day, I was reluctant to do it and never thought I’d be brave enough to share the pictures. But I knew that these images might help other people who have felt the same anxieties as me. I wasn’t ready, but I just did it. I’ve wasted too much time feeling uncomfortable – when you get opportunities like this, you need to step in the arena and show up.”

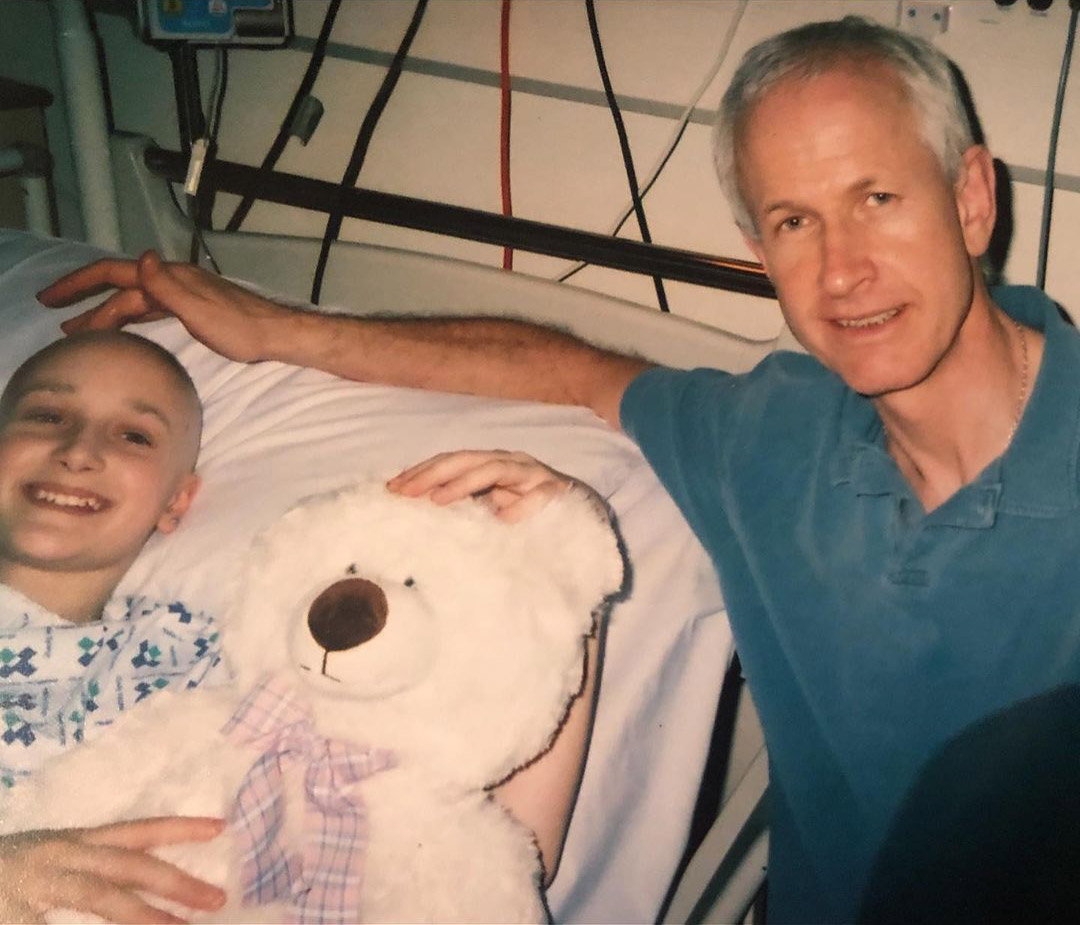

Grit and determination have been key themes in Amy’s life. When she was 13, she was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a type of bone cancer. It’s rare and makes up only 0.2% of all cancer diagnoses in England. “I was always a sporty kid, growing up in Norwich in the ‘two-leg’ days. I went back and forth to the doctors for a year with a mystery pain in my knee, which they thought was growing pains. When they discovered it was cancer, I was given a 50% chance of survival. I’d lost my mum, uncle, and grandparents to cancer, so I thought, ‘Ok, this could be it’.” When chemotherapy failed to slow the osteosarcoma’s growth, her leg was amputated. “I went back to school as a bald kid with no eyebrows and eyelashes, I was in a wheelchair and I had one leg. Like most teenagers, I was self-conscious. I just wanted to be normal and would do anything to hide it.”

Noticing that his daughter “was feeling lost”, her dad, who Amy says is her biggest champion, encouraged her to go to a wheelchair basketball taster session. “He thought that sports could help me to get back to myself,” she recalls. “I always think it’s cool when athletes say they immediately fell in love with a sport. That wasn’t me,” she laughs. “I hated it at first. I was awful. I’d spent so much time learning to walk again and hiding my leg under baggy tracksuit bottoms that the thought of wearing shorts seemed like a backward step.” A few things changed her mind. “Watching the GB women’s paralympic basketball team on TV; I loved seeing strong, confident women who were the polar opposite of me. I realised that the wheelchair game is just as hardcore as the running version too, and it’s the same sized court, baskets and the same rules.”

defiance

Extra-curricular basketball gave her confidence that proved vital as a young woman who was figuring herself out at that time. “I was the first person in my school with a disability. I couldn’t fit in the doorways of classrooms. There was no lift, and P.E lessons were me throwing a ball against a wall by myself. I didn’t know anyone with a disability, and then I met all these people who were just owning it. I realised that nothing in life can hold you back, as cheesy as it sounds.” Since making her international debut at the 2010 BT Paralympic World Cup, Amy has been a major player in the Great Britain Women’s squad, including at London 2012 and Rio 2016. At the 2012 Games, she was the top point scorer in two of Great Britain’s games before, four years later, helping the team to achieve the highest-ever finish by a GB women’s team at the Rio Paralympic Games when they secured fourth place.

She has four European bronze medals to her name and was part of the GB Women’s teams that broke records by claiming silver medals at both the 2018 World Championships and 2019 European Championships. It’s nothing short of impressive, given that she taught herself basketball by watching YouTube tutorials. “When I lived in Norwich, there were no teams and no coaching. It was just my dad and me in an outdoor court until it went dark,” she remembers. “I’d get dog poo in my wheels; we’d train without the floodlights on because it was cheaper. It took a long time to get selected for the GB team. I’d have a pity party whenever selection came around and I wouldn’t get picked, but my dad would encourage me to keep going. He’s the person who’s taught me the power of positivity and seeing the best in life.”

In the past year, she’s proud of having found a healthier balance between sport and downtime. “I was really unhappy in Tokyo, and I realised that I was always waiting for the ‘next thing’ to be happy,” she recalls. “The next tournament, the next medal… I decided to move to London with no real plan. I’m just going for it and seeing what happens. “I’ve been modelling alongside basketball – that’s new for me. Even if it’s box-ticking, it helps to raise awareness and push me out of my comfort zone. I did a catwalk, which I thought I’d never do as I’m conscious about my walk. I’ve been going to classes like Zumba and puppy yoga. I’m all about new experiences.” Another big joy in life is travelling. “I went to Slovenia on a whim because the tickets were £13 and I recently took a trip to Iceland, but I was having issues with my prosthetic leg so I had to travel in my wheelchair. Not bringing my leg was quite a scary step, but it was empowering too. I had to speak up and ask for help where I needed it.”

Training sessions are tough, around five times a week, mixing skills with cardio and conditioning. “I have a ‘yass queen’ playlist that gets me in the zone,” she says. Think: Megan Thee Stallion and Cardi B. Her dream rest day would be a massage, a three-hour bath and binge-watching Dance Moms. “I’ve learnt to give myself days just to do nothing but relax.” Recently, the UK has started the first women-only Premier League for wheelchair basketball. Amy says it’s a step in the right direction for visibility and encouraging more women into the sport. She also thinks that Channel 4 did an “incredible” job of broadcasting the 2020 Paralympics. “People think that wheelchair basketball is gentle passing and baskets on the floor. Disability sports are real sports. Most people don’t realise that able-bodied people are allowed to play in the teams at a National Level. My sister plays with me now. People ask if it’s disrespectful, but my sister will admit, she’s the worst player of us all.”

Social media has undoubtedly been a game changer and having a public profile has allowed Amy to be visible to other young women navigating similar thoughts, feelings and anxieties. “Don’t get me wrong, social media can have a lot of negatives and there’s a comedy aspect too. In Tokyo, I got hit in the head, fell out of my chair, arms flailing, and that became a meme on TikTok,” she laughs. “But if any kid is about to lose a leg and thinks, ‘my life is over’, I want to know that they can see other people succeeding on Instagram. That’s a big driving force for me. I never really saw that growing up because it was before social media days. Disabilities do not hold you back anymore. “I never thought I’d accept my leg,” she adds. “I thought I’d always be so embarrassed and self-conscious by it. If I could go back in time, I’d tell myself, ‘It’ll be OK’. It’s such a waste of time holding yourself back in a world that’s already so complicated and full of other worries. Be your own hype man.”

Editorial Design by this is root

Title Image by James Cannon