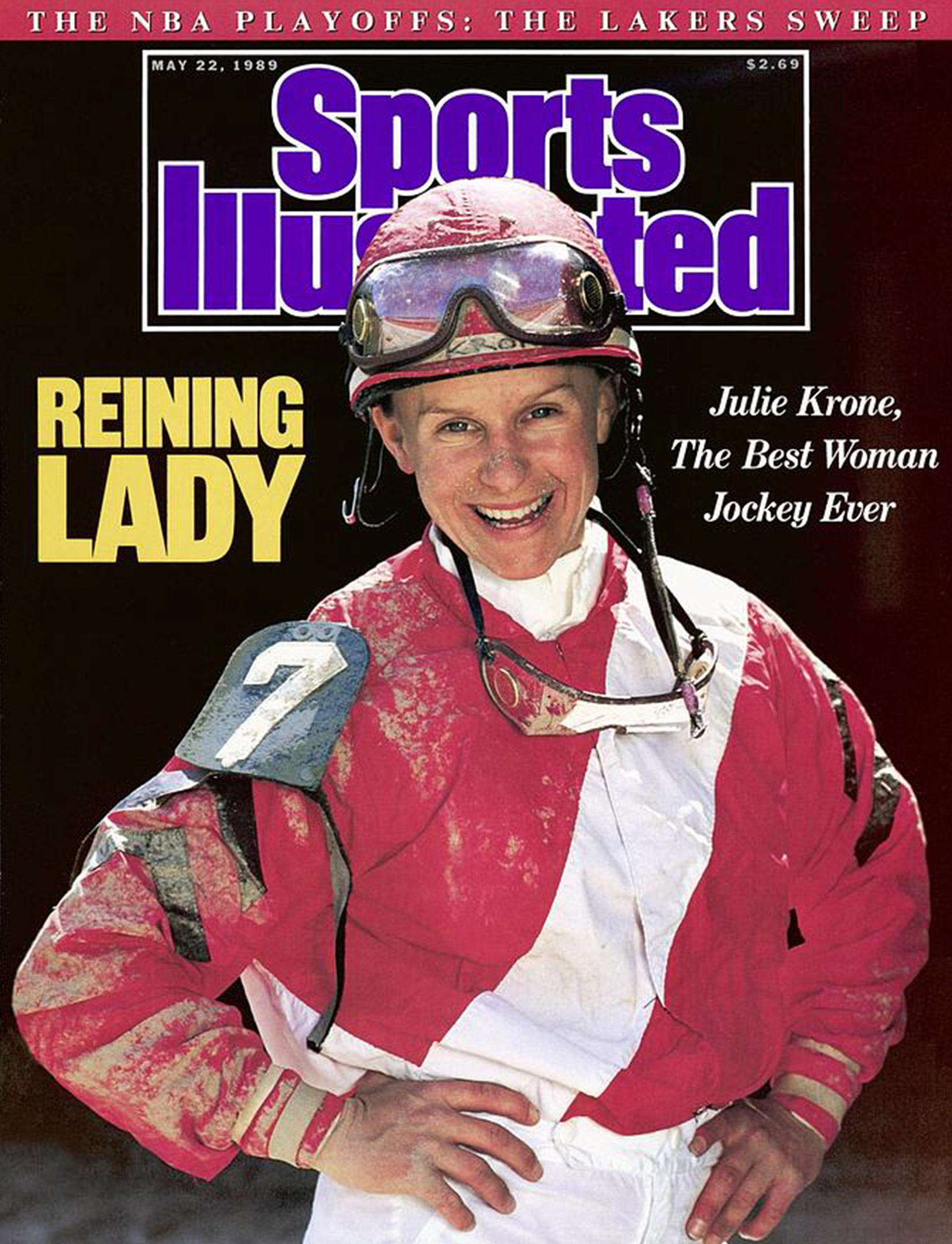

Pioneer: Julie Krone

As one of the world’s most celebrated Thoroughbred jockeys, Julie Krone tells us about entering a man’s world, injuries, comebacks and triumphs, and how being a mother means more to her than anything

By Sarah Rodrigues

In 1993, Julie Krone became the first female jockey to win a Triple Crown race, riding Colonial Affair to capture the Belmont Stakes. She remains the only woman to have done so; additionally, in 2003, she became the first female jockey to win a Breeders’ Cup race on the championship day, having continued to ride even after the 1993 accident that nearly took her life.

“I have an ability to overcome adversity,” she says. “I can get on with getting over it or directing my energy into some other area that might help.” It’s an ability that she called upon again over the course of the pandemic. “I called on every resource available to me,” she laughs. “I went through all the phases – I tried everything. I tried wine for a while; we baked everything that you can possibly bake; I listened to podcasts.”

Julie is married to writer Jay Hovdey and they have a daughter Lorelei, entering her senior year in high school. For somebody with a career as outstanding as Julie’s, it seems astonishing that we speak for so long about family life (“You have to play pickleball!” she exclaims at one point. “It’s the funnest thing I’ve done in a long time. Google it as soon as we get off the phone!”) before turning our attention to her achievements.

Perhaps in this day and age there would be many who’d argue that Julie’s successes should be celebrated on the basis of being, simply, a jockey, and that the emphasis on ‘female’ should be ignored. Nevertheless, as a petite woman (she’s just 4’10½” and weighed less than 100lb as a jockey) with a charming, childishly-pitched voice, she endured more than her fair share of derision from her male counterparts.

“It’s funny because when I think about my life as a jockey and the stories to share with my daughter, they’ve just all melted away like ice cubes or something,” she says. “But sometimes I can still stir up these feelings of anger about certain situations.” There was, for instance, the groom who was in charge of the barn in which Julie was doing her apprenticeship who told her that, despite how great she was at communicating with the horses, she just wasn’t “strong enough.”

“He referred, in particular, to my upper body strength,” recalls Julie. “And I was just so irate – this guy just infuriated me – so I literally went and joined a gym that night and by the end of the year I was competing in muscle shows.” She acknowledges, however, that her skill has always been recognising a horse’s traits before even getting on its back. “I could have a horse figured out just by the way their body had developed,” she says. “I could sit there, ringside at a racetrack, and watch horses walk in all day long and tell you about their personality traits.”

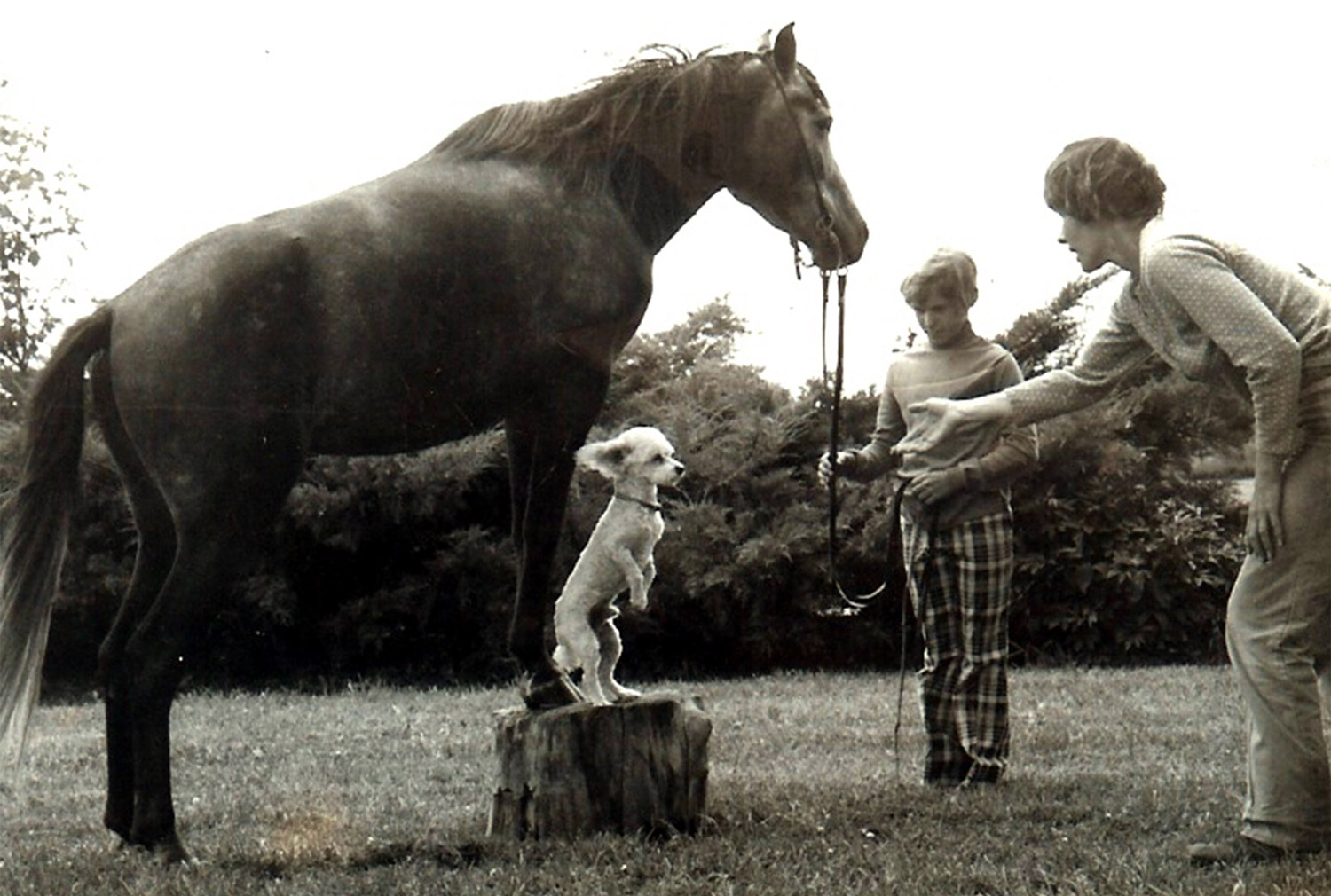

She credits her mother, Judi, with the development of this intuition and the thoroughness of her training. “My mom would teach horses how to do circus tricks like laying down, bowing, kneeling and rearing up. And often it would be with no lead ropes on them.” There’s a level of trust and confidence that’s essential in building such relationships – the cues, she says, are as subtle as winking, or biting your lip. “You can teach a horse to do, at liberty, anything they do in nature,” she continues. “I developed relationships with horses that were so intense, where just a flick of the ear or a change of expression would mean something.” When she made her way into the world of racing, therefore, all of that intuitive training put her in a strong position. “In racing, the horses are pretty much just trained to go forward,” she says.

“I was tempted to join the circus,” she laughs. “My mom had a lot of circus friends and I still do, actually. I did some acrobatics and gymnastics but it’s not something I ever really pursued.”

INTUITIVE

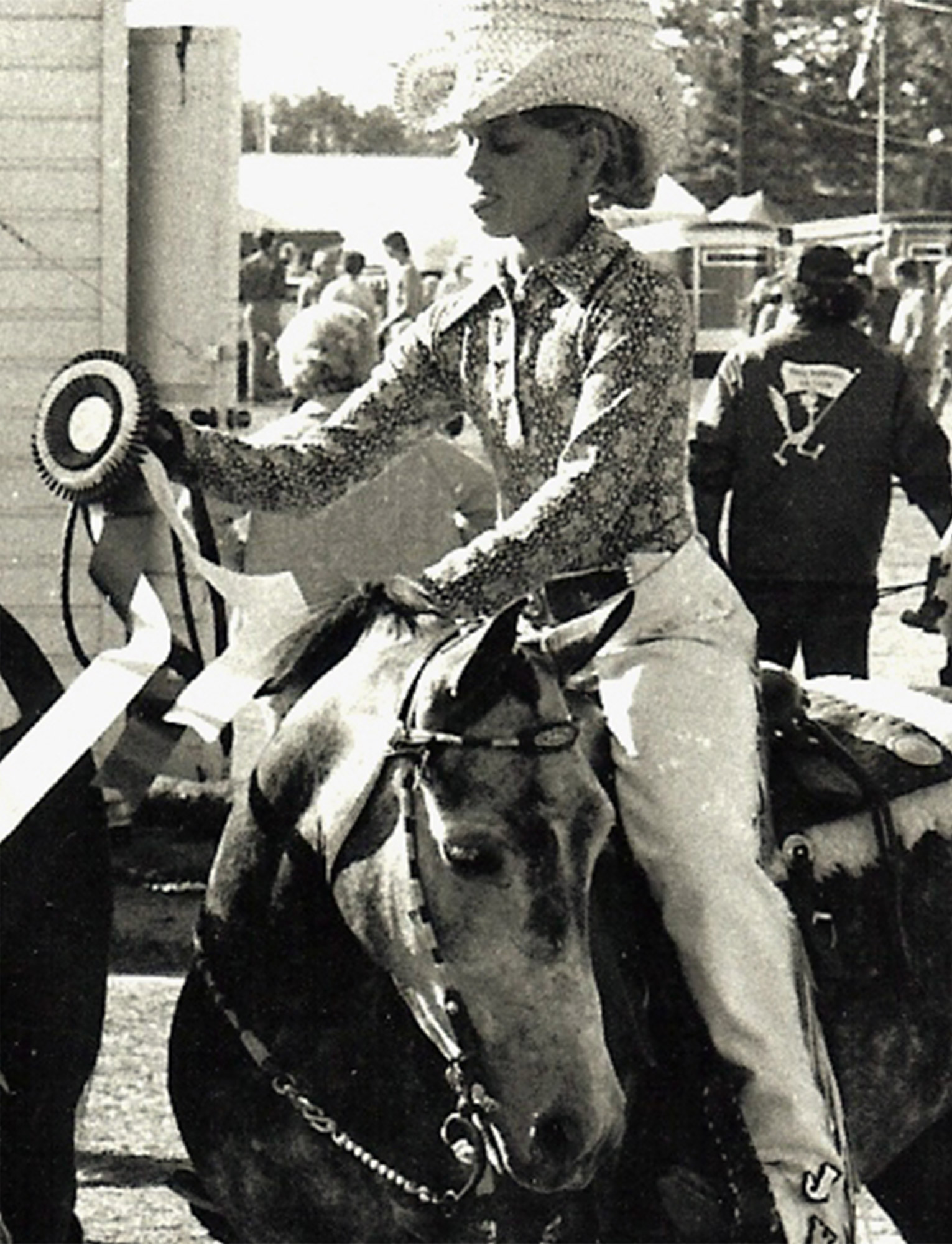

Julie’s first trophy came at the age of five when she was competing against kids three times her age. She downplays the win (“It was leading Shetland ponies around and making them stretch out”) and her mother was always hard on her. Their relationship, as Julie acknowledges, had to evolve as Julie moved through her teen and adult years – something that seems to inform the evidently strong bond that she has with her own daughter. “I really wasn’t allowed to do anything other than horses,” she says. “I can see now that horses were absolutely everything to my mom, and I’m not necessarily like that.” It’s her daughter that she credits with the broadening of horizons that later life has brought her. “We were riding horses one day and she said ‘Mom, I have to tell you something … I don’t like horses like you do. I want to do theatre!’” that horses were absolutely everything to my mom, and I’m not necessarily like that.” It’s her daughter that she credits with the broadening of horizons that later life has brought her. “We were riding horses one day and she said ‘Mom, I have to tell you something … I don’t like horses like you do. I want to do theatre!’”

Given her achievements in the face of all kinds of adversity (even if one wants to minimise the issue of gender, the severity of her 1993 injuries cannot be understated) it says a great deal about Julie that she does not ever seem to have reached a point at which success and enjoyment are things to be taken for granted. “Thanks to my daughter, I got really into theatre and I have so much fun with it. Who knew that I could paint?” she marvels. “Who knew that I could sew costumes? I love the people and it is just such a fun thing to do.” Despite continuing to ride after her 1993 injury, she retired a few years later in 1999 and started as a commentator and analyst for the TVG racing network and Hollywood Park.

“When I quit, I was at a point where I was just over it,” she says. “I was not willing to take that chance anymore; of falling and getting injured. There’s a very definite line between when you do want to be a jockey, and when you don’t want to be a jockey. No one can talk you into it, and no one can talk you out of it.”

When it comes to relationships with people, Julie would seem to apply the same empathy that makes her so adept at communicating with horses. She described, for example, her work as an agent during the 2020 racing season for jockey Ferrin Petersen, less in terms of her own input and far more in terms of what Ferrin has encountered on her career path in racing. “When I didn’t want to be a jockey anymore, I found it really difficult to make myself heard,” she says. “And, on the other side of the equation, it was the same for Ferrin. She’s a certified veterinarian and acupuncturist and she has spent years training. Because of this, she struggled to make people appreciate her ambitions in jockeying.”ed veterinarian and acupuncturist and she has spent years training. Because of this, she struggled to make people appreciate her ambitions in jockeying.”

So what was it that got Julie back in the saddle, as it were? “I was at the racetrack every night with Hollywood Park, talking about jockeys and which horse was going to win,” she says. “And before too long, I started thinking, ‘Man, I can still do this. These guys aren’t that good. I could ride with these guys!” Coming out of retirement in late 2002 led to what Julie refers to, casually, as “a fun, successful little eight-month stint in California.” It was only when pressed that she says “yeah, it was pretty freakin’ cool. I won two $1-million-dollar races and a Pacific Classic at Del Mar. I was pretty impressed with myself.” The “little stint” was punctuated by a mid-season injury, and she retired once and for all after injuries suffered in December of 2003. It’s indicative of how little Julie dwells on the severity of her near-fatal injuries that she’s scarcely shared the details of them with her daughter, with whom it’s apparent she shares a great deal. And yet, her daughter has read about this tough period in her mother’s life.

Julie’s injuries in that 1993 race have been well-documented. Less than three months after her triple-crown triumph, she suffered a terrible accident when her horse, Seattle Way, was clipped by another. Although Seattle Way did not fall, Julie was thrown onto the track and trampled by four horses, one of whom would surely have crushed her chest, were it not for the fact that she was wearing a flak jacket. Now standard gear for every jockey, Julie had only, weeks before, started wearing one on the advice of fellow jockey Jerry Bailey.

Julie suffered a broken elbow and a fractured right ankle that was damaged so severely that amputation of the foot was considered before the joint was finally repaired with a piece of bone from her hip and many stabilising metal plates and screws. “The injuries were bad; it took every bit of everything I had to overcome them,” she admits. “But then I started thinking about all of those other moments that aren’t so bad. You just have to try to control your brain and let the bad memories float away and replace them. It’s important to recognise that those thoughts are not doing any good.”

Empathy

Being diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was a breakthrough for Julie. “I barely even knew what that was,” she says. “It was just at that time when athletes were on the cusp of talking about their vulnerabilities but – especially as a female athlete competing against boys – the last thing I wanted to do was to admit to everyone that I was scared. In reality, however, when I started sharing my experience, it was actually really comforting. It helped a lot more than it ever hurt.” Once she recovered, she still wanted to ride. “I didn’t have any problem with the possibilities – I was like ‘bring it on, I’ll take my chances,” she says. Although, she admits, “it definitely affected my relationship with the horses at first – my residual fear, my flashbacks, my intrusive thoughts – they were terrible. I had no read on a horse at all. But,” she continued brightly, “it all came back.”

Sharing continues to be important in Julie’s approach to life. “Energy and sharing,” she agrees. “I was listening to a TED Talk and they were discussing ways to fend off old age. One of them was establishing and maintaining relationships with people you enjoy being around.” What does the future hold? Julie remains active in support of Lorelei’s aspirations as a strong supporter of community theatre, and she is hopeful that she can renew her Junior Jockey Camp concept that was sidetracked by Covid-19 restrictions. Julie is also working closely with Frankie Lovato, Jr., North America’s Eclipse award-winning apprentice jockey of 1980, who is the inventor and manufacturer of the popular Equicizer that simulates the riding of a racehorse. The Equicizer is used for physical therapy and conditioning by athletes, hospitals, and rehabilitation centers around the world.

In terms of career highlights, there’s no doubt that Julie has had more than a few, including being the first woman jockey (and still the only) inducted into the Thoroughbred Racing Hall of Fame. Yet, despite her brutal injuries, her brave comebacks, her unprecedented (and as yet, unmatched) triumphs, it’s her role as a mother that so clearly means more to her than anything she ever did on horseback. “My mother introduced me to horses, and my daughter introduced me to theatre,” she says with evident pride. “When she got awarded for her performance in one play and I got an award for the costumes, standing up there with her felt immensely special. Even after everything I’ve done, you can’t beat that shared mother-daughter experience.”

Thanks to Julie for supplying images, including those taken by her father, the late Don Krone, an accomplished photographic artist who taught in high school for many years.

Editorial Design This Is Root