Pioneer: The Pinnacle Club

Finding they were being treated unfairly compared to their male climbers, one group of women started their own club, which is still breaking boundaries over 100 years on

By Rachel Ifans

“Women are here; women are everywhere”. Picture the scene: It’s the early eighties and you’re driving up a mountain pass in north Wales, only to see those words freshly daubed all over the side of the Climbers’ Club hut in paint. Gill Price, climber and member of The Pinnacle Club, the UK’s only national rock-climbing club for women, remembers the thrill of seeing those huge painted letters that day: “You drove up Llanberis Pass and they were frantically trying to clean it off. It was very uplifting.”

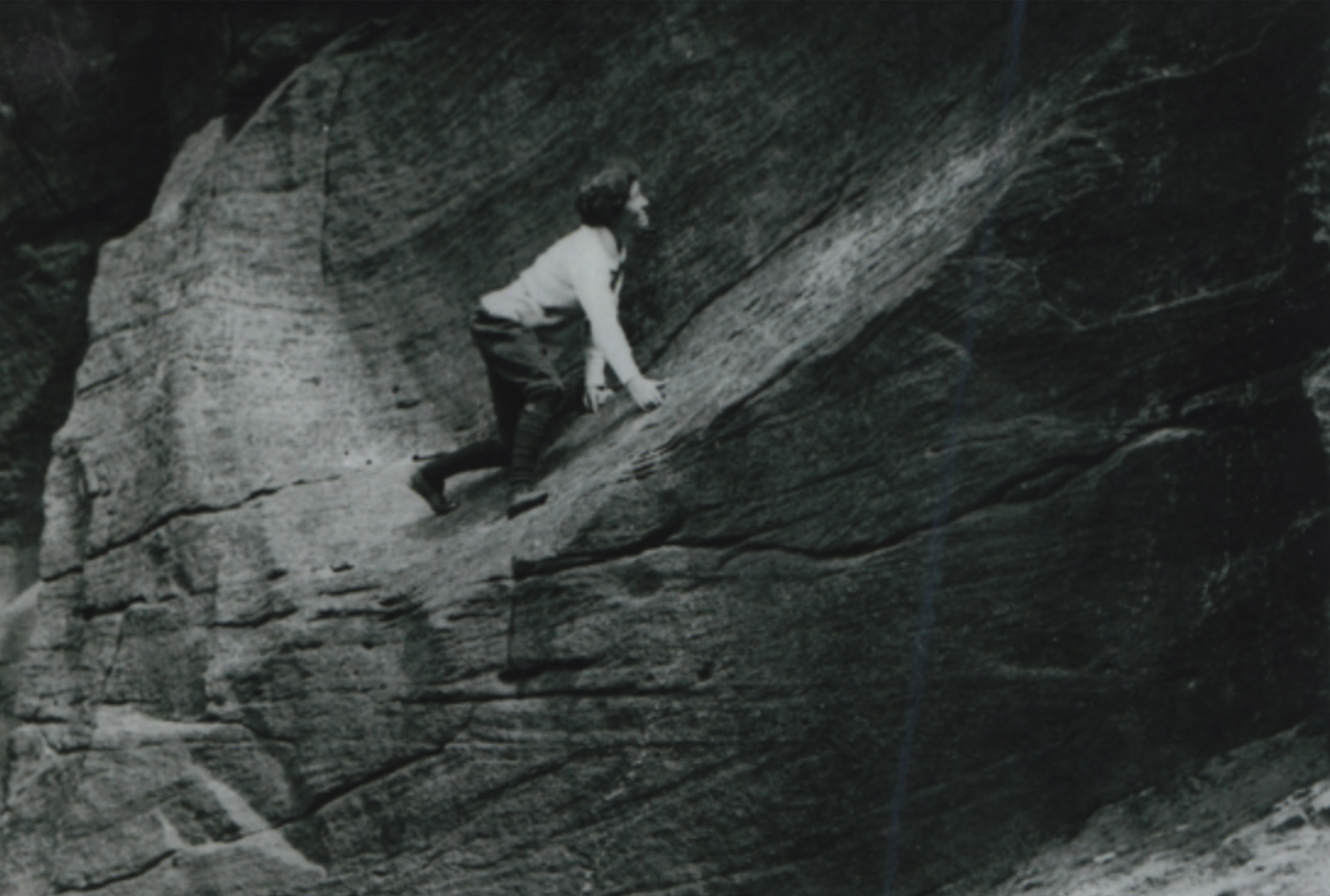

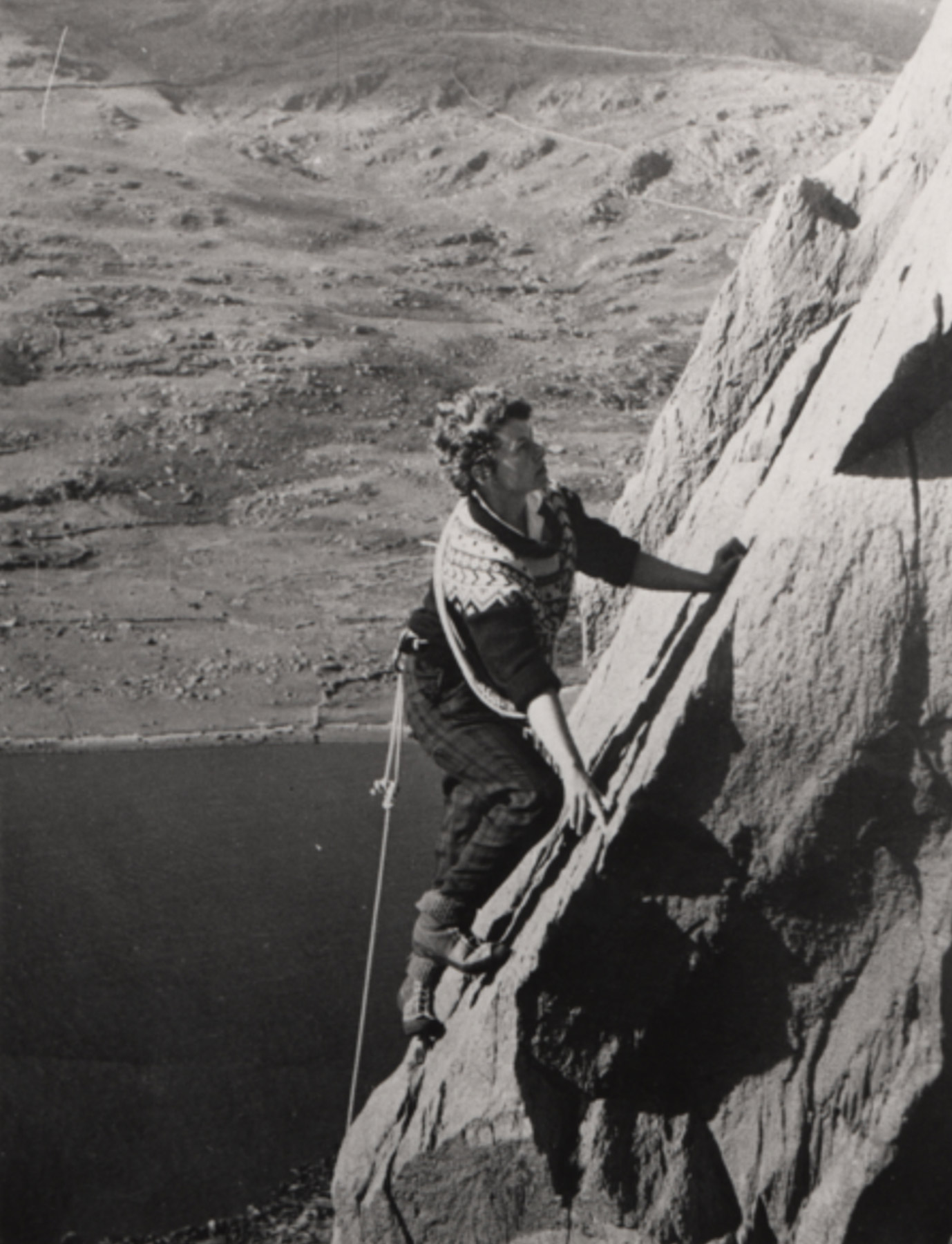

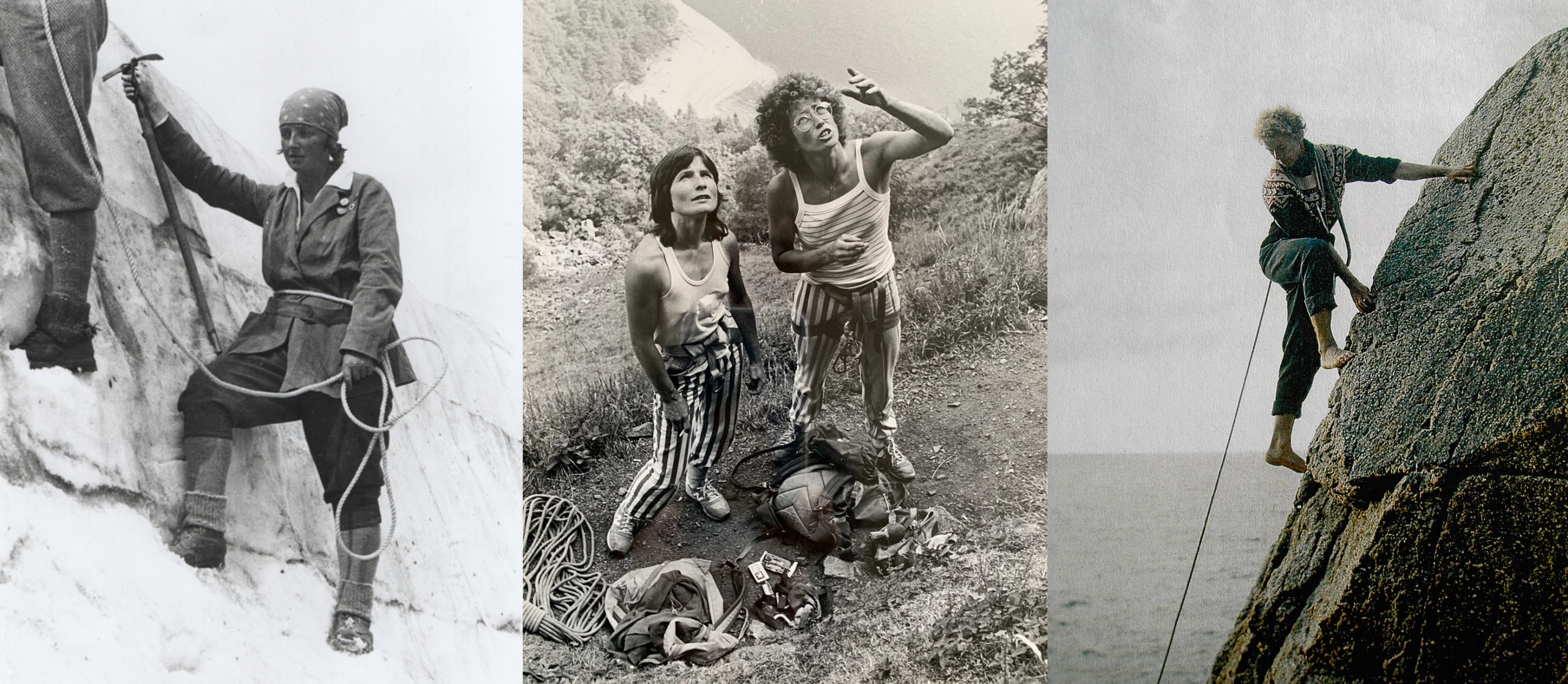

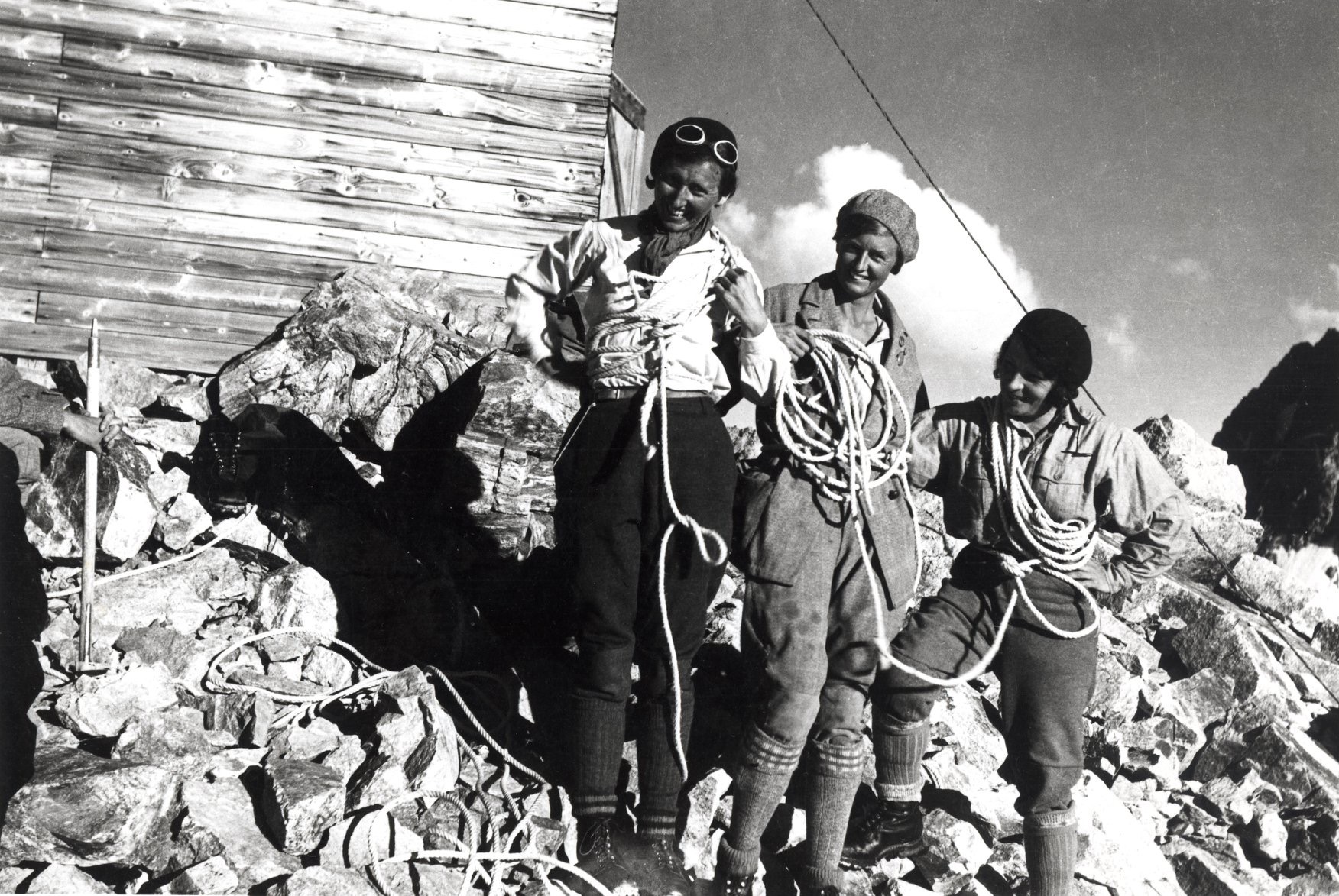

When you start delving into the club’s history, the names of its women become icons of daring-do, women’s liberation, endurance and determination. From Emily Kelly (‘Pat’) who created the club in 1921; to founding members Dorothy Pilley, Lilian Bray and Annie (‘Paddy’) Wells, who made the first all-female ascent of an Alpine climb, the Egginergrat, in the same year; to Gwen Moffat, the club’s longest-standing member and the first female British Mountain Guide in 1953. And there are many more equally important stories of camaraderie, identity, personal boundaries, world travel and lifelong friendships. These women would rather be tied to the side of a cliff than the kitchen sink.

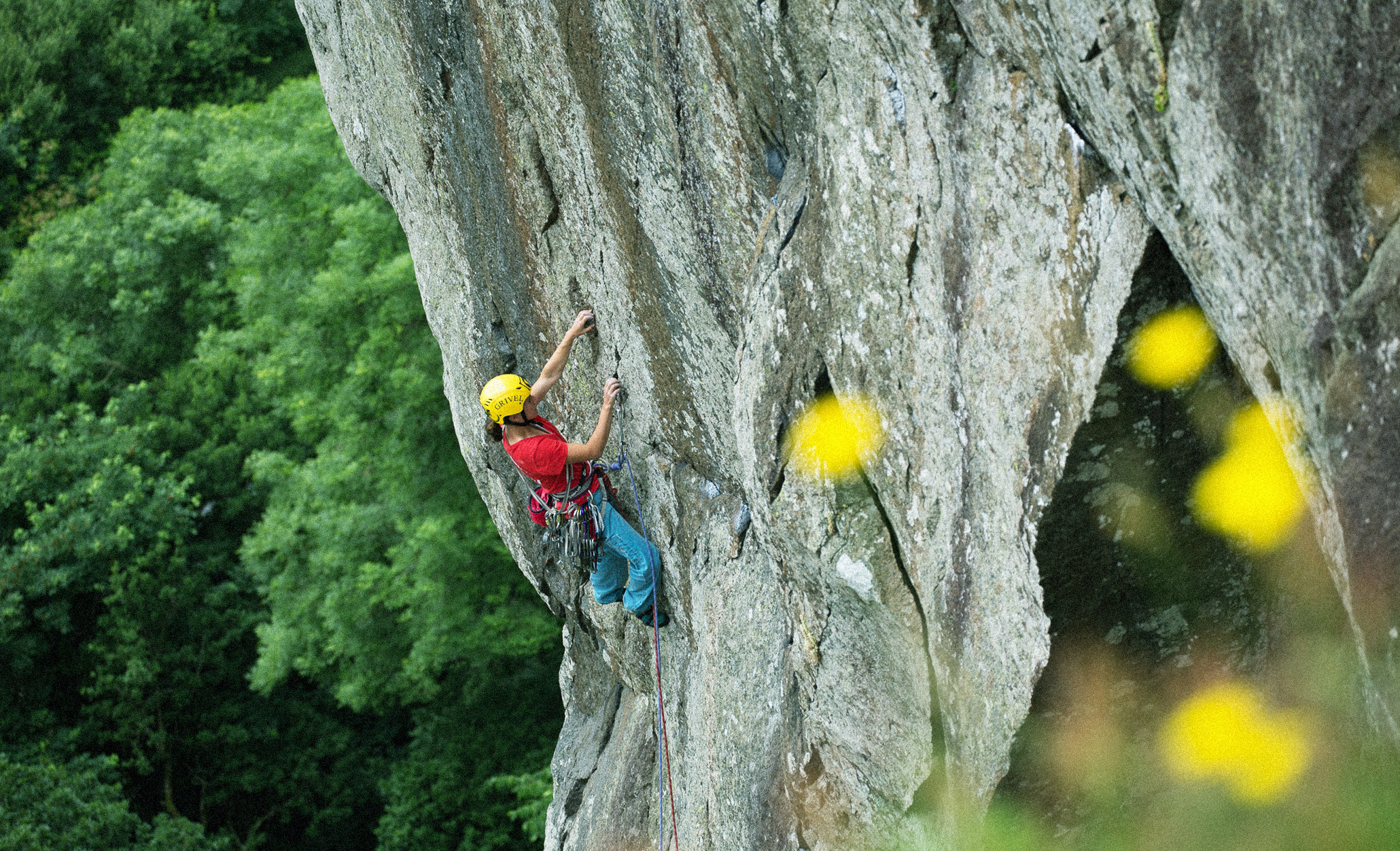

Although climbing today is almost unrecognisable from when the club was founded – in terms of kit, standards, the numbers of women taking part and competing at the highest levels – there’s still much to do. As the Club itself said in its centenary year in 2021, until women achieve full parity, the need for the Club remains. The Pinnacle Club’s focus is on trad climbing – where you place your own protection; meaning, for example, putting a sling around a spike of rock with a carabiner on it and then clipping your rope into the carabiner so that if you fall, you don’t fall far. The club’s archivist Margaret Clennett explains: “In the 1920s and ‘30s, you didn’t have the gear you have today. The old adage was ‘the leader does not fall’. This was because, back then, if the leader fell, they’d probably die because they’d fall such a long way. For this reason, the best climber was always the leader, and that tended to be a man.”

camaraderie

So, although a minority of women did climb back in the earlier days of the Club, they were never allowed to lead. As Josephine Scarr says: “As a woman, you were always on the bottom end of the rope. I thought it would be fun to be on the leading end of the rope so that’s what I did.” Margaret explains: “It became a tradition that Pinnacle Club would teach women to lead, because there were no climbing courses then. One of the qualifications of membership is the ability to lead; you have to be able to demonstrate that you can place gear properly and that you can look after your second.”

TRADITION

The Pinnacle Club trio’s 1921 ascent of the Egginergrat without male companions or guides was followed up in 1928 by Bray and two other Pinnacle Club members who conquered the Cuillin Ridge on Skye for the first time as an all-female posse. After that there came a deluge of firsts for Pinnacle Club members. Nea Morin traversed the Meije in the Dauphine Alps in 1933, and Brenda Ritchie became the first woman to lead a route on the renowned crag Clogwyn Du’r-arddu on the flanks of Snowdon two years later. Ascents continued in locations as close as Llanberis and as far as the Himalaya.

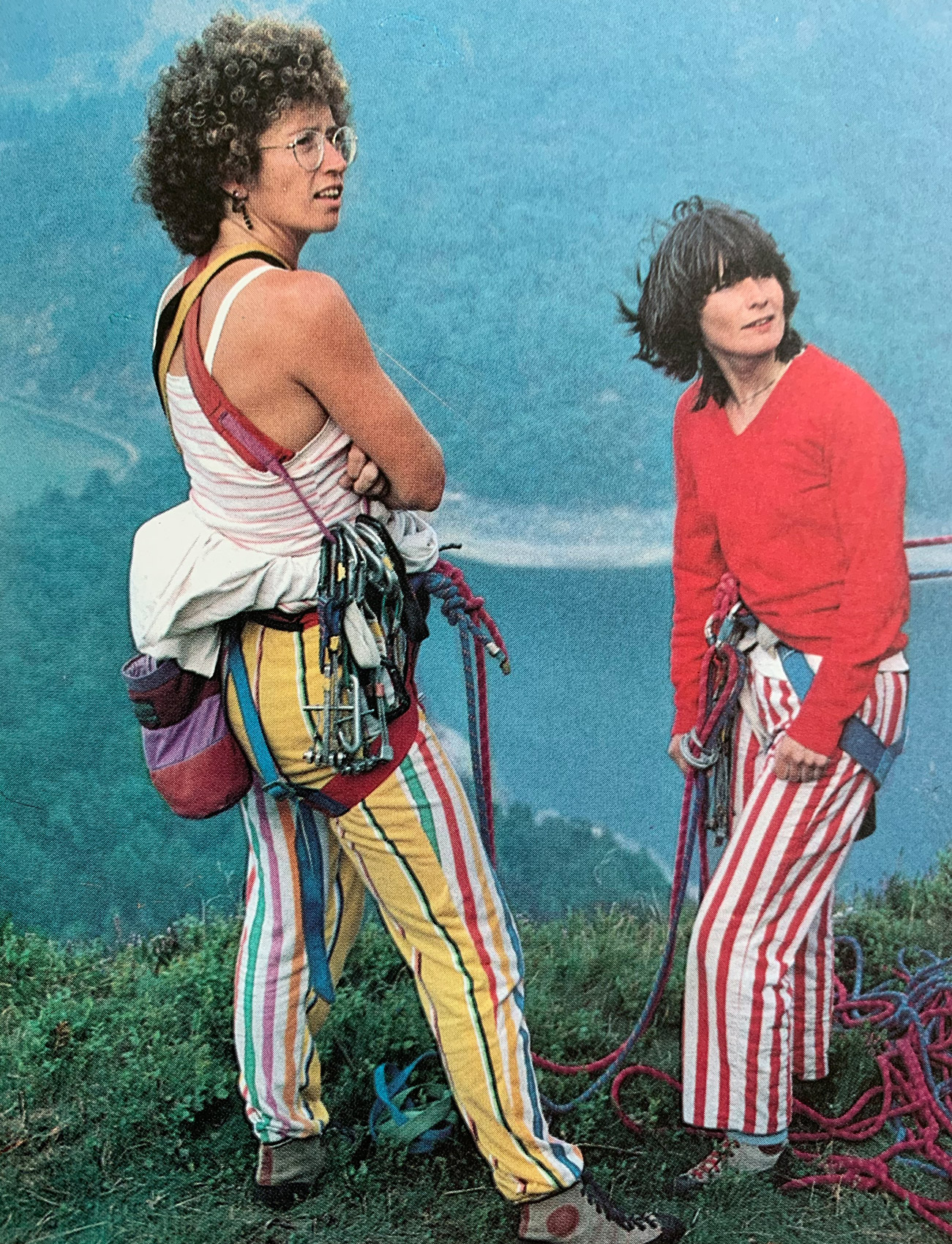

In 1984, the Club, supported by the British Mountaineering Council (BMC), ran an international women’s meet in North Wales, with the 40 top female climbers from all over the world taking part. Pinnacler Jill Lawrence made the first female ascent of the iconic Right Wall in Llanberis at that meet, a climb that was graded E5 and meant she was the first British woman to lead a climb of that difficulty.

The 1984 meet has gone down in The Pinnacle Club history books. Angela Soper, organiser of the meet and a fantastic climber herself, said of it: “Everyone seemed to raise their grade that meet. There was an amazing atmosphere that you get when you have a lot of enthusiastic women together; there’s a feeling that, if she can do it, I’ll have a go.” Just three years after that meet, Angela and fellow Pinnacler Cynthia Grindley made the first all-female ascent of the Old Man of Hoy, a sea stack in Orkney. Margaret, who joined the club in 1979, says: “In the beginning, it was easy for people to go and do groundbreaking things; it’s much harder to do today unless you’re a professional climber or you go to somewhere really esoteric.”

The club is about way more than notches on the cliff-face. Margaret reflects on the challenges women climbers faced back in the early days. “We don’t have to fight the prejudice that the original pioneers did,” she says. Simple barriers like the fact women were expected to wear skirts while climbing in the early days. Dorothy Pilley’s 1959 journal entry describes: “Dear Pinnaclers, to escape condemnation I used to walk out of the village in a green tweed skirt over baggy knickerbockers well hidden till the foot of the climb.”

Pinnaclers have always liked to refuse society’s narrow expectations of them. Way back in the 1940s, Jean Drummond was defiantly battling the norm: “Mother didn’t work; she was always tied to the kitchen sink. That was not going to be the life for me.” And even decades on, in the 1980s, climbing women such as Alison Cairns found a sense of identity in a world they sometimes didn’t fully understand. She says: “I’m not interested in shopping or interior design or having kids. All I was interested in was climbing… our whole life was built around going away and that was considered very odd. I found I had little in common with most of the women that I met… the Pinnacle Club was about meeting kindred spirits.” “We’d put the babies on the ground on a blanket and then we’d go bouldering. We were no distance away so there was no danger of them being eaten by a sheep!” says Hilary Lawrenson.

Identity

And many members led a double life, even in the early days. The wonderful Dorothy Pilley recorded in her Climbing Days book: “And so to finish off with a struggle up the Gribin Angular Chimney and a slide down the Monolith Crack before the night journey back to London. How the contrast shook one! To go back to gloves and high-heeled shoes, pavements and taxicabs. Walking with an umbrella in Piccadilly one felt as though with a little more strain one would become a case of divided personality… The strangeness of the dual life made, in those days, a cleft, a division in my mind that I struggled in vain to build some bridge across. Kind, firm friends would say, ‘You can’t expect all life to be a holiday’… But to me, and to climbers before and after me, this was no question of holidays. It went down into the very form and fabric of myself.”

Sally Macintyre understands how climbing gets into your DNA: “It was a huge part of my identity. Even now that I’m not really climbing, if I’m asked [to describe myself] I’d say I’m a climber. It’s always been important that I have a skill, some experience, something I can do that is quite special and has taken me to wonderful places.” Jessie Leong is one the club’s newest and youngest members. She explains: “I get a sense of leaving my other life at the door and, as soon as I enter that space, it feels special and I feel protective over it.”

The friendships made through The Pinnacle Club can be surprising, often spanning generations (members range from 20-somethings to 90-somethings), demographic and experience. For Jessie, two climbers in particular have become very important to her. The first is Hilary Lawrenson, who encouraged Jessie to take part in the 2016 international meet.

Adventure

She explains: “I wasn’t super experienced at climbing multi-pitch routes in the mountains at a high level but I was invited to come along. Hilary was president at that time so she was influential, and willing to offer mentorship.” And then there’s Val Hennelly, who Jessie affectionately calls her Adventure Auntie. She says: “I took her on an adventure in Northumberland last year. We went out of our way to find these bothies and hiked up a fell in the middle of nowhere. It was such a long day but we got to this big viewpoint and had a cup of tea together watching the sun set.”

The Pinnacle Club has always been about enabling women to rock climb. Jessie says: “As a young person, a big consideration for me was how I would get to meets. I didn’t have a car so it was impressive how much the other members did to make sure that people like myself could get to the remote locations.”

The Club celebrated its centenary in 2021 and as it looks forward to the next 100 years, it wants to widen its enabling ethos, putting diversity at its heart and recognising that there are still limitations for women to get to the crags. The Pinnacle Club Centenary Sponsorship Fund will support women who otherwise wouldn’t have the opportunity to climb, and its aim is to increase participation of women from a whole range of under-represented groups, including ethnic and religious minorities, LGBT+ and disabled women, and those from financially and socially disadvantaged backgrounds.

Jessie says: “I hope I can look back at our centenary when we’re celebrating 150 years of the Pinnacle Club and I’m one of the oldies that they’re wheeling out to talk about what the club has meant to them over the years!”

The Pinnacle Club won funding from the National Lottery to compile and archive its history as part of its centenary celebrations. It’s a real treasure trove of audio clips, journal entries, documents and testimonies: https://www.pc100.org/menu

And watch the film here

The Pinnacle Club website is here

*L-R: Photography by Alpine Club Photo Library, Photography by Border Television, Photography by JR Lees.

Editorial Design This Is Root