Rose Reilly: The Girl Who Wouldn’t Play Ball

Gender play and accolades: “Once upon a time, there was a little girl in Scotland, who was actually a little boy.” We chat to Rose Reilly, whose determination has taken her far in women’s football

By Alice Snape

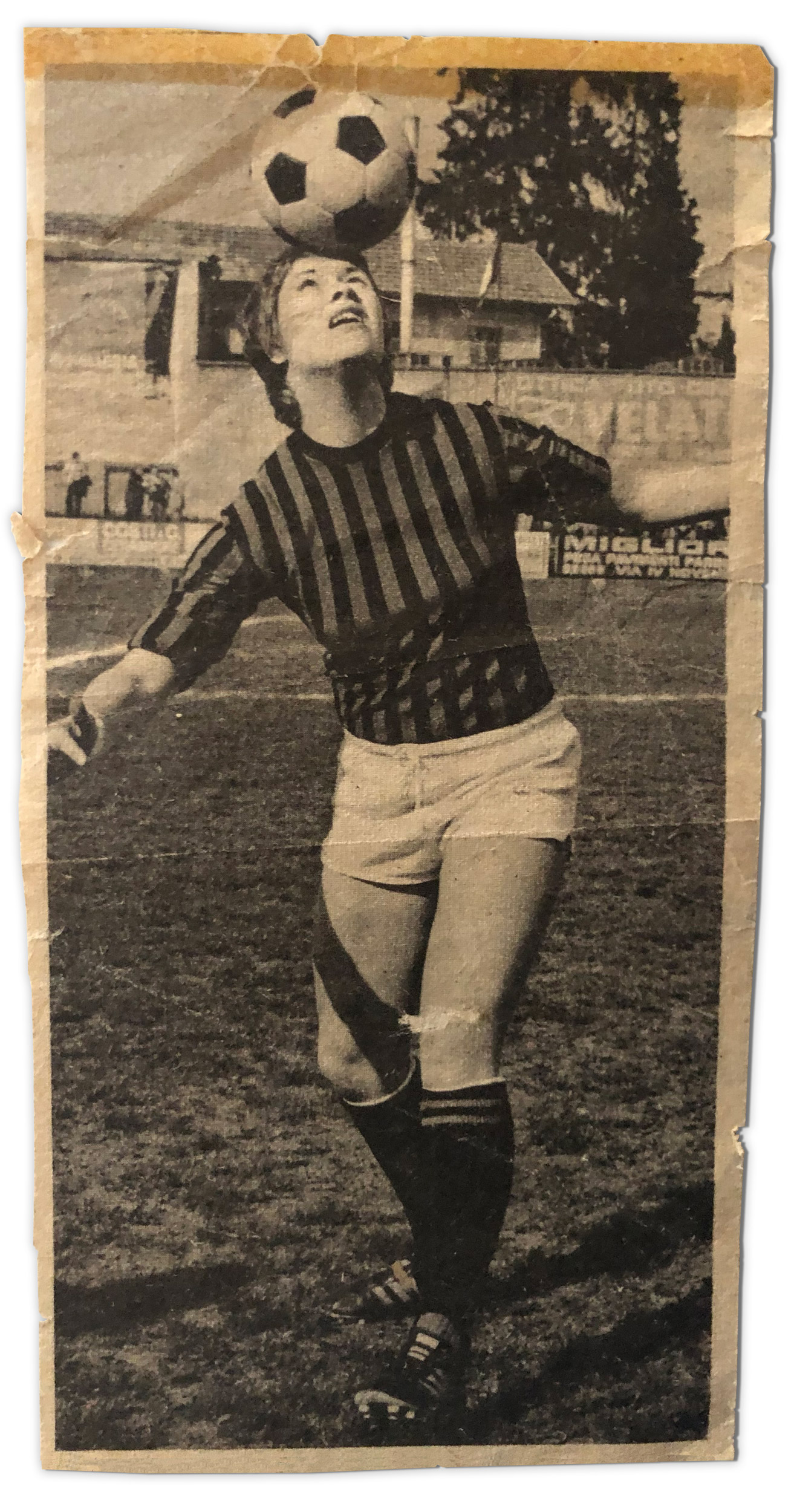

In 1984, Rose Reilly became the first Scottish woman to win the World Cup. She’d grown from being a “wee girl” in a park in Scotland to playing professionally in the majestic San Siro stadium in Italy. A true trailblazer who wasn’t trying to set the world alight, she just had a passion for football that saw her run, dribble and score her way into a man’s world and change it for generations to come.

In early 1970s Scotland, women’s football had been banned since 1921, considered unsuitable for the delicate female frame. Unperturbed, 17-year-old Rose Reilly left her Ayrshire home, packed her belongings into a cardboard suitcase – which broke at the airport meaning her dad had to take off his braces to keep it together – and headed for Europe to fulfil her childhood dream of becoming a professional footballer. Little did she know that she was blazing a trail that would pave the way for women’s football. “I won’t take no for an answer,” Rose asserts defiantly in her strong Scottish brogue.

This grit and single-minded dedication to carve out a path as yet untrodden first showed itself when Rose was three-years-old. She wandered away from her family home in Stewarton, and somehow her little legs carried her to a patch of ground that had been turned into a football pitch.

“I was drawn to it,” Rose recalled. “That’s where my mum and dad found me – a wee bit away, around a few corners, ‘cause I didn’t know where I was going; the attraction to football was just always there.” This serendipitous moment sparked five-year-old Rose to write a letter to Santa asking for a football of her own. “I got a doll. I was devastated,” Rose says. Of course, that doesn’t stop a girl who won’t accept no for an answer. “I went out, found a wee boy who had a football and swapped it for the doll.” That ball became her cherished possession, a beacon of who she would become.

Defying gender roles became her standard practice: “Once upon a time, there was a little girl in Scotland, who was actually a little boy,” is how Rose begins her story. But it wasn’t so much that she was unafraid to step outside prescribed gender stereotypes of the era, it was her steely determination to play football at any cost – much to the dismay of her parents. “We’re talking about the late ‘50s, little girls didn’t play football,” Rose explains. She faced sexist attitudes and deep-rooted misogyny from all corners; then SFA secretary Willy Allan was even quoted in the newspaper as saying: ‘We just don’t approve of ladies football.’

Rose’s dad was in insurance and her mum was a nurse, she grew up in a “procreating working-class Catholic family,” and was one of eight children, including two sets of twins, of which she was one. “My brothers and sisters were, let’s say, ‘normal’ kids who fitted into stereotypical roles,” Rose says of family life. “They all obeyed the rules, but I was different.” When she was seven years old, Rose asked if she could play with the local boys team.

The manager said yes, on the condition that she got a haircut and changed her name to Ross. She went straight to the barbers and asked for a short back and sides. “I told him my mum would come in and pay later,” Rose recounts with a deep chuckle. “It was a small village where everyone knew everyone. He said, ‘are you sure your mum knows?’ I said yes! So I went home with this haircut and my mum nearly murdered me.”

It’s how she earned her kit, though – one she had to put on at home before heading to the pitch to play, as she couldn’t get dressed in the boys’ changing rooms. In one particular game, there was a Celtic scout looking for boys to sign. “I scored about eight goals, I was running riot and the scout wanted to sign the number seven – the ‘wee boy who got all the goals’. My manager told him, ‘You can’t, she’s a wee lassie!’ I was devastated that I couldn’t play for Celtic, I just thought if I’m good enough, then why not?” A motto that would become the chorus for her life, singing it to herself, loud and strong, nothing would stop her.

“When I was nine years old, I played for a team of women aged between 20 and 40,” says Rose, who had been initially turned away as the female coach thought she was a boy. “I had some gender issues, for the boys I had to turn myself into a boy, then I was told I couldn’t play with the women because they thought I was a boy. I was all mixed up.” This was the first time Rose was allowed into a dressing room. “All these women felt massive to me, they were wearing these gigantic bras,” says Rose on the subject of women’s bodies. “I thought they must all be mummies! It was surreal. I guess I just didn’t give a shit about how I looked.” Unabashed, unashamed, her body allowed her to play, it’s an attitude we could all use a sprinkle of.

Her inability – and lack of desire – to follow rules got her expelled from secondary school for playing football, meaning that teenage Rose ended up taking a job in a carpet factory in Kilmarnock. She hated it and was eventually sacked, but her mile and a half walk to work allowed her space to think. Before she’d even started work each day, she’d lived out a fantasy life in her mind. It’s how she conjured up a plan to make her footballing dream a reality. She managed to get sponsored by her local newspaper The Daily Record, and travelled to France for a trial at Reims. Rose’s talent shone bright and she was signed at half-time. Reims was a stepping stone, and she was there for six months before being scouted by AC Milan.

When she moved to the Italian metropolis, she spent the first year living in a hotel room. “I’d never even been in a hotel before then,” she remembered. She didn’t know the language and her teammates spoke not a word of English, so in the evening, she’d speak to herself in the mirror. “I was the only person I had to talk to,” Rose said matter of factly. “There wasn’t even a television in the room. So I bought a dictionary, because I’d seen this pink newspaper, it was called La Gazzetta dello Sport, and it was a daily football paper. I thought, wow this is great. I bought it, but was like, fuck I cannae read it. So I’d learn three words a day from the dictionary, I couldn’t do four, because I was too thick,” she says with dry self observation, meaning you’re never quite sure if she’s joking. But Rose immersed herself in the Italian way of life, chatting to locals, and within a year, she’d mastered the language. “I even started drinking espresso, but nearly spat it out, I thought it tasted like poison. But everything Italians did, so did I – I embraced their way of life. It’s where I found my people, my connection.” Her teammates are still her best friends.

So from Rose to Ross, now she was Rosa living out an Italian dream. But she continued striving to be the best possible player she could. “Even when I turned professional, I’d get up early and train on my own in the morning, then with the team in the afternoon. Always trying to better myself.” Ahead of the curve, she was even practising mindfulness, before it became the multi-million pound business it is today. Her home stadium in Milan was the San Siro; with its brutalist structure and a capacity of 75,923 fans, Rose used to walk out onto the empty pitch to get herself into the right mindset. “I’d wander in and take possession of the stadium,” Rose explains. “I’d walk up to one goal and say to myself, ‘I’m going to score in here’. Then go to the other goal and say, ‘I am going to score in here’. I possessed the place. Here I was coming into this majestic stadium, and I looked at the goals and thought, but that’s just the same as my local park. I didn’t know what I was doing but nowadays it’s called mindfulness and all that shite. I was streets ahead, doing it before it had a name.”

Dream

Rose was part of the team that won the 1984 Women’s World Cup; she was named female footballer of the year and became a household name in her adopted Italy, but she was never bothered by accolades and cups. “I just gave them away to the fans. I know I won it, these guys can keep the trophy for the rest of their lives.” And even though she received a lifetime ban from the Socttish Women’s FA in 1975, she doesn’t hold grudges. “I was always a Scottish heart beating under an Italian jersey,” she said.

Ever defying societal expectations, she got married in her early 40s, and discovered she was pregnant at 45. “I was never bothered by age. As a professional athlete, your period is erratic because you’re putting your body through hell. So I got to 45 and thought I was menopausal, but I wasn’t.” She took to her new role with vigour, again defying any prescribed notions of what a mother should be. “The day before my daughter was born, I was down at the beach in Turin in Italy. I was waddling around like a whale. There was a burst ball coming up in the tide, so I started playing keepy-up with it. Playing keepy-up in the sand is difficult, playing with a burst ball is near impossible. Doing all this with a huge belly where you can’t even see the ball. I just had this wonderful moment, with my daughter due and I will always remember it.”

But she hasn’t passed her passion for football to her daughter. “She’s a black belt in Taekwondo and was also a ballet dancer. But she’s just like her dad, she’s too zen, you know meditation and Reiki,” said Rose of her daughter and husband who she lives with back in her hometown of Stewarton. However her daughter has inherited her drive and passion. “She’s an activist. Out marching and shouting for Black Lives Matters and LGBTQ+ rights. She wants to change the world and she’s only 20, so she thinks she bloody well can.”

Legend

Now aged 67, Rose has finally had her legendary status acknowledged in her birth country, with induction into the Scottish Football Hall of Fame, the Scottish Sports Hall of Fame, and an honorary degree from Glasgow University, which she accepted with a speech in her signature style. “I said, my message to you is don’t listen to your mum and dad or your professors – just do what you want. Do your best in whatever you’re doing, even if you’re the cleaner, just do the best for yourself. I got a standing ovation.”

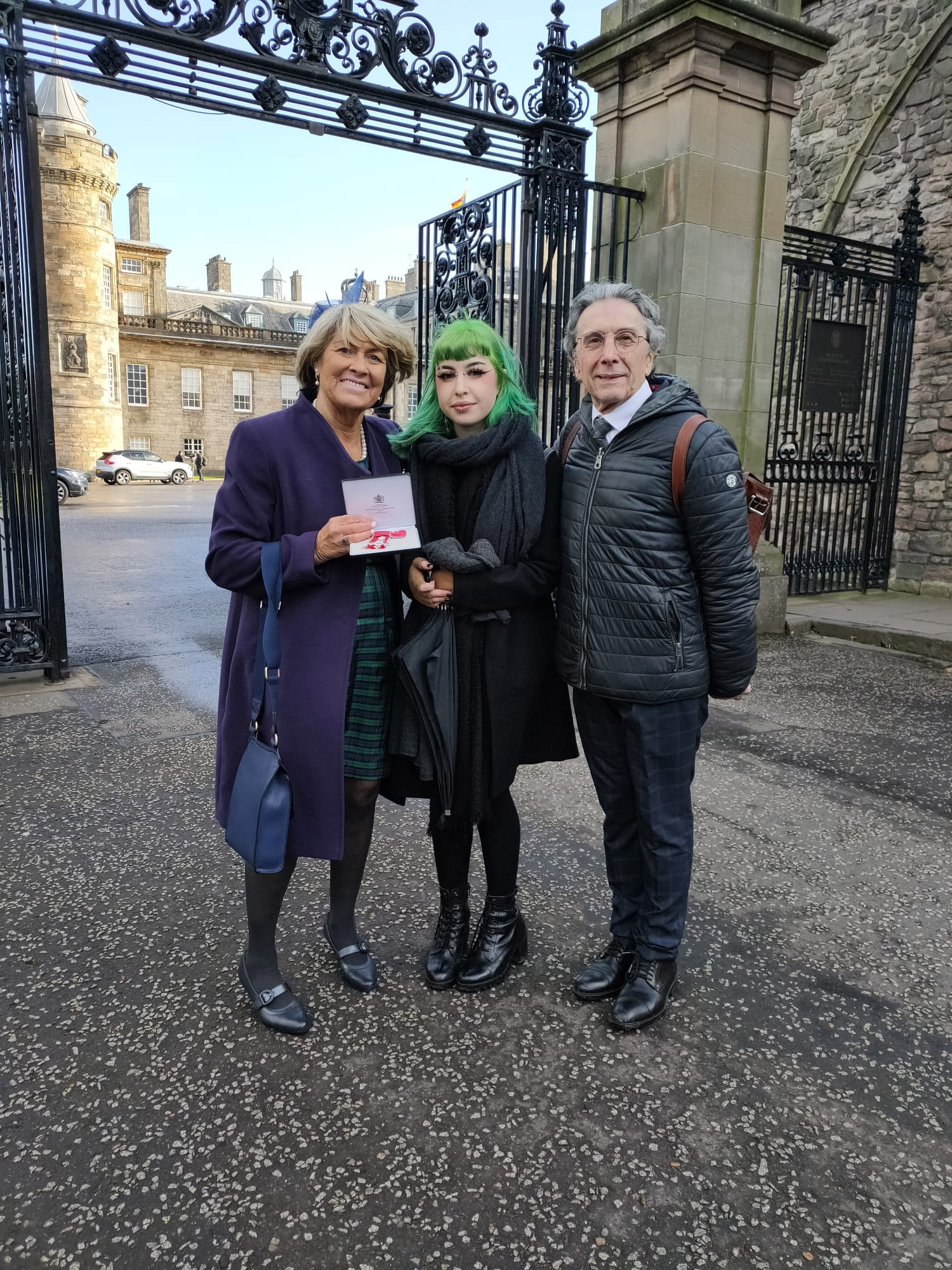

In 2020 Rose was awarded an MBE in the New Year’s Honours list, but due to Covid, it was not until January this year that she received her award from Princess Anne at Holyrood House. For the occasion, Rose picked up a dress for a fiver in a charity shop. “It was about ten sizes too big for me, but it’s the tartan I like – bottle green and navy blue – so I took it to a local seamstress to make it fit.” Like a metaphor for her life, she’ll always make something work if she wants it enough.

Rose retired from football aged 40. She opened up a sports shop in Sicily, so she certainly kept on working, but she’s never played again. “When I stopped playing, that was it. End of. I have too much love and respect for what I’ve done,” Rose states without a hint of regret, but of course she still keeps fit. “I am a morning person, I’m up at 5am for my run, 6am doing my housework, and taking the dog for a walk. I get up before other people get out, I’ve always been like that.”

And you can forget the awards, Rose has marked what truly means the most to her indelibly – on her skin – in ink. “I love tattoos, but my husband doesn’t and I couldn’t give a shit,” said Rose defiantly, she doesn’t care what anyone thinks of her or her choices – in fact she never did. Among her collection of tattoos there’s an outline of Sicily – “where I left my heart” – an Italian flag on her wrist, a Claddagh instead of jewellery for her wedding ring and a rose that wraps up her leg from her ankle to her knee. The buds represent her, her daughter and her husband. “The thorns are there because life isn’t easy,” Rose explains. And it certainly hasn’t all been roses for Rose.

She’s been described as a trailblazer; there wasn’t a path but it didn’t matter, because she carved one out, one that paved the way for many women footballers to come: “You have to have the humility to learn. You blame yourself and better yourself. I think that’s lacking in today’s game. That’s just my point of view – and it isn’t a criticism,” said Rose, who believes that self-criticism is the key to success.

“The girls are getting paid well now and they travel the world.” The truth is, she has passed down a legacy, even if she didn’t know she was doing it at the time. “The game has evolved, there’s a feminine side to it now,” said Rose. “Back then it was more masculine because it was seen as a masculine sport. Everything’s different now. But I don’t give advice because I always hated getting advice.” She does want more young girls to get into football in Scotland though: “We’re not at England’s level yet,” she says simply. And 40 young girls, aged eight-years-old, are now being given a chance to play in Rose’s hometown of Stewarton, at a sports centre that has been named after her, and to play for Stewarton Annik Girls FC. It’s where Rose used to play and where it all began.

“This is where we need investment, so what I’ve done for those wee girls is to help give them a future in the game,” Rose declares passionately, and this clearly means more than any award she’s ever been adorned with. “There may be elation when I have won a match, but there’s a feeling of warmth when I think of my work with the sports centre. I love those wee lassies,” she continues, full of affection. “I want to instil healthy eating habits and healthy relationships to their bodies because they are fed so much crap and unattainable expectations from magazines and social media. I want them to be confident in being themselves, they are different sizes and shapes, and that’s just us, that’s just being a woman. They don’t have to be the best, but I want them to feel part of a team.”

Rose was driven by passion. The recognition and hint of fame she is experiencing now is a mere side note in her story. “I have been interviewed so much, usually by men. I’m such a feminist and they are so patronising. The male chauvinistic way, asking what did your husband say? And I’ll answer: ‘Well it’s actually none of his business, it’s my story, not his’.” Last year Rose’s life was brought to life through a play titled “Rose – Play, Pie and a Pint” that ran in Edinburgh, Glasgow and Greenock, and most recently in Milan.

And even though work is underway on a film by Skye-based Chris Young, producer of The Inbetweeners, with the working title “Life of Reilly”, which she jokes might make her a millionaire, she doesn’t want anything else, she wouldn’t move house or buy a fancy car. “I don’t care what car I drive, it’s blue and that’s it,” she quips. “And anyway, I am the richest football player, nobody has won what I’ve won.” And no one can steal that crown, but, let’s face it, she wouldn’t care if they did.

TRAILBLAZER

Editorial Design by Root