Wisdom Of The Waters

Meet the Jeju freedivers of South Korea and find out how etched wrinkles and sun-bleached skin convey beauty, strength and freedom found through fierce independence

By Darcie Imbert

Photography by Hyungsun Kim

We originally told the story of the haenyeo divers of Jeju Island as a tribute to their incredible tradition, and now we’re revisiting it because these women are at the heart of a new Apple TV+ documentary, “The Last of the Sea Women”. Directed by Sue Kim, the film highlights their continued fight against both environmental and cultural threats, portraying the fierce, funny, and hardworking grandmothers who dive to the ocean floor without oxygen. With many of the haenyeo now in their later years, their way of life faces greater danger than ever before, but their spirit of resilience is inspiring a new generation to rally around them. The documentary shines a light on their close-knit community, their determination to preserve their ancestral traditions, and their growing influence on younger divers and the world beyond through social media.

Becoming acquainted with the female freedivers of Jeju threw my understanding of ageing into disarray, urging me to contemplate the western social structures that are perhaps more prone to ageism than one might expect, and question how I participate in a culture that steadily eclipses an entire generation. Haenyeo translates as ‘women of the sea’, and refers to the centuries-old female fishing community that plunge to the depths of the bitterly cold ocean to harvest seaweed and shellfish from the seabed.

Upon researching the female freedivers of Jeju, I felt a sense of misjudgement. The term ‘mermaid’ continuously appeared, depicting the divers as mystical, otherworldly figures. Whilst these might be used as terms of endearment, I felt that describing them in this way was unashamedly rewriting the haenyeo history of hardship and resilience, and undermining the invaluable lessons they teach. One of the most poignant learnings from my conversation with the divers was their warning against this estrangement, President of the Haenyeo’s Association, Kang ae-Shim warns: “We must teach the younger generation about the haenyeo and their practises as a natural rule, not as a foreign culture.” To begin to understand the motivations of the haenyeo, we must first unpack the patriarchal structures and perilous conditions that the tradition was borne out of.

Between the East China Sea and the Korea Strait, situated 80 km south of the mainland, stands the volcanic island of Jeju. Whilst presenting challenges to mass scale farming, the rich and fertile landscape of volcanic soil prompted the growth of primary industry; islanders could fish, rear cattle, and grow agricultural produce. This dependence on natural systems cultivated an acute understanding of the island’s ecosystem and led to the emergence of coastal and mountainous communities that depended upon the land for survival.

Much like other small-scale producers on Jeju, sustainability lays at the core of haenyeo life as it is intrinsically linked to their livelihood; the fishing system continues to adhere to age-old traditions that ensure preservation, following a calendar that prevents harvesting during the reproductive season of sea species. When the central government launched its regional development strategy in the 1960s, the island of Jeju was developed into a tourist destination to serve the emerging class of Korean elites and global travellers, turning traditional aspects of island life into points of interest, including the haenyeo.

As the course of tourism progressed, building a rose-tinted screen between residents and visitors, the stories of the divers and the work they undertake have become somewhat romanticised. This sentiment is described by photographer Hyungsun Kim whose works accompany this feature, he has been shooting the haenyeo for seven years: “Most haenyeo are not happy or cooperative about the shooting as they don’t see why I would want to photograph them.”

“They are tired after five hours of diving, they curse and yell at me because they want to get back to sorting or just want to go home and rest. After getting to know them for days and helping them around with heavy loads of the catch, I got to know them more and became friends with them.” Whilst this discursive shift has liberated the women from their underclass status in traditional society, it risks undermining the importance of their work as a pivotal moment in the history of Korean women. Literature suggests that it was originally Jeju men who plunged beneath the surface to retrieve the fruits of the sea until the king conscripted large numbers into his army whilst demanding fruitful supplies of abalone still be sent to him, in response, the women assumed the role and took to the ocean.

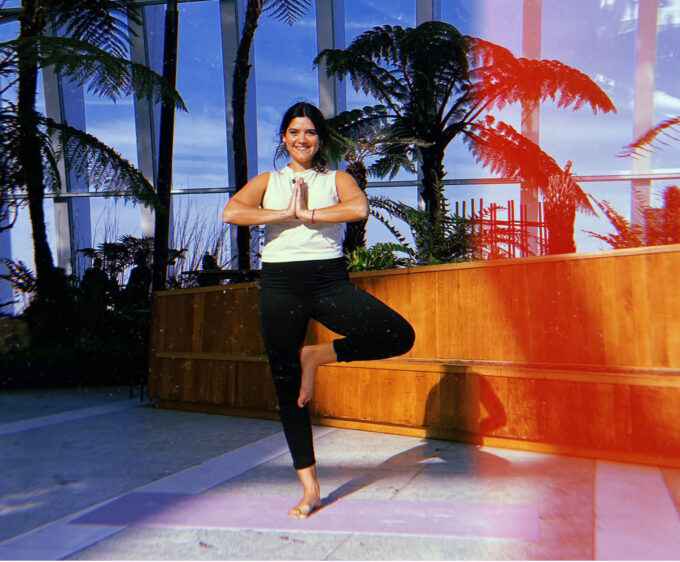

MOVEMENT

Jeju has suffered a troubled history; largely understood to be the tipping point that led to the Korean War, the Jeju Uprising of 1948 wiped out an estimated 30,000 people, one tenth of the population, a turning point that set in motion the matriarchal structures that exist today. Up until the 1970s, the haenyeo wore loose cotton garments to dive in, even in the depths of winter when the island can experience light snowfall and gusty -5° winds. When the government finally understood the importance of the haenyeo in preserving Jeju’s traditions, and the subsequent tourism interest that followed, they subsidised the cost of wetsuits which enabled them to spend longer periods at sea and continue to dive into old age, likely contributing to the large number of over 70s that work today.

Most Western societies have created a culture of retirement, both professionally and socially; constructing a society prone to ageism, with a tendency to subconsciously limit the agency of elderly people through concern, ‘you should slow down’, ‘I will do that for you’, ‘you shouldn’t be doing that at your age’. The divers we spoke with were quick to dismiss the stereotypes attached to old age and the pitying that often comes with it, Ko Song-ja notes: “People may think that old haenyeo are ignorant, slow, and lack understanding, but they are not,” Kang Ae-Shim comments, “Don’t look down on haenyeo!”

The haenyeo community dispel the link between retirement and old age, removing age from the criteria of their social status in place of merit, empowering the senior divers to make their own decisions whilst they’re able to, and teach younger generations about their cultural practices. Photographer Hyungsun Kim emphasises the sense of community that exists amongst the women, he tells of the supportive structures that enable them to continue to work within a collective and maintain their sense of agency well into their eighties; researchers claim the oldest haenyeo was 92 years old.

He notes: “Haenyeo have three hierarchies, Sang gun, Jung gun, Ha gun (meaning high-middle-low level), Sang-gun haenyeo dive about ten metres deep and catch most of the seafood like abalones and octopus, these are usually women in their 50s and 60s as they have skill and better stamina. Jung-gun haenyeo work around five metres deep, and ha-gun Haenyeo work on the shoreline where the ocean is shallow. Most of the older haenyeo work within the ha-gun group.”

Hyungsun Kim has shot over 300 haenyeo over the years, capturing them as they make their way onto shore, exhausted, after up to seven hours at work; their deeply etched wrinkles and sun bleached skin convey the indescribable beauty found in strength, and the sense of freedom found through fierce independence. In a short film produced by Patagonia, one diver reminisces about the women who would visit from Seoul: “They would have these beautiful, pale faces, and our faces were dark and tanned, but I can make money and I have freedom.” Their existence is a rebellion against the rigid patriarchal structures that existed in Korea’s confucian society. The haenyeo did what they had to do in order to support their families, some even continued to work throughout pregnancy, eventually giving birth on the boat in the middle of the ocean, later attaching their children to the mast whilst they worked.

In conversation with diver Kang Ae-Shim, the president of the Haenyeo Association, she is keen to point out the many ways in which haenyeo contribute to society: “Just one example is the export of conch and seafood, which contributes to foreign currency and fuels the domestic economy. Not only do we provide economic support to our families, we contribute on a larger, national scale.” She also speaks of their socio-political impact as leaders of the Korean independence movement against colonial Japanese occupation. Ae-Shim has experienced the evolution of haenyeo culture, from being shunned by society to being recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity: “I went to Ababa to attend the ceremony where Jeju haenyeo culture was deemed a World Cultural Heritage. I will never forget the moment the decision was made. Thinking back to the old days, I would never have imagined that we could have been recognised on such an honourable occasion. What an incredible achievement!”

INDEPENDENCE

The work undertaken by the divers is treacherous and difficult and, as better opportunities arise for Korean women, numbers of haenyeo dwindle. In one interview a diver noted that the very reason why many of the women made the life decision to dive was so their children wouldn’t have to; it enabled them to fund their education with the hope that it might lead to better professional opportunities in the service industry on the mainland. According to the island’s museum, in the 1960s up to 23,000 haenyeo were working around Jeju; they estimate fewer than 5,000 remain dotted around the island today, despite government efforts for preservation. In Seogwipo, where a large proportion of haenyeo work, the City Office reported just 1,579 haenyeo in its jurisdiction at the end of 2019, down 50 from the previous year, although this was offset by 14 aspiring haenyeo who were newly registered in 2019.

In recent years, a small number of young women have left their lives on the Korean mainland to become haenyeo, parting with their stressful city careers in order to reconnect with nature. The haenyeo we spoke with stressed the importance of national policy in preserving traditions, but insisted the responsibility lies with the senior divers to support and educate an emerging generation of divers and teach the wisdom of the waters. In many ways haenyeo are agents of change, an invaluable source of wisdom. Their lives depend on an intricate understanding of the ecosystem in which they play a part, owing to their profound respect for the environment. In spite of dwindling numbers of divers, the haenyeo represent an alternative vision for the future, their centuries-long tradition is teaching a more considered approach to fishing that might be the antidote to our broken, pillaged ecosystem. In the wake of unprecedented global environmental activism emerging from the bottom up, the tradition of haenyeo is far from disappearing; it’s evolving and taking different forms on an international scale.

Photography by Hyungsun Kim

Editorial Design by Root